Why Right-to-Repair Will Decide the Future of Your Devices

This deep dive unpacks the laws, technologies, incentives, and controversies that will decide how long our gadgets last and how fixable they really are.

Figure 1: Smartphone repair in progress, symbolizing the growing right-to-repair movement. Source: Pexels (CC0).

Mission Overview: What Is Right‑to‑Repair Really About?

Right‑to‑repair is a global movement arguing that consumers and independent technicians should have the legal and practical ability to diagnose, maintain, and fix the products they own—without being locked into a manufacturer’s authorized service network. It cuts across smartphones, laptops, game consoles, tractors, medical devices, and home appliances.

In recent years, coverage in outlets like Ars Technica, Wired, and The Verge has chronicled how this once‑niche cause is now reshaping policy, product design, and even corporate reputations.

At its core, the mission of right‑to‑repair is threefold:

- Restore practical ownership of devices people purchase.

- Reduce e‑waste and extend device lifespans to cut climate impacts.

- Preserve competition in repair markets and prevent monopoly control over fixes.

“If you can’t fix it, you don’t really own it.”

— Kyle Wiens, Co‑founder and CEO of iFixit

Legislative Landscape: How Laws Are Rewriting Device Longevity

The right‑to‑repair debate has moved decisively into legislatures and regulatory agencies worldwide. Governments increasingly see repairability as both a consumer‑rights and environmental imperative.

United States: State Laws and Federal Momentum

In the U.S., multiple states—including New York, Minnesota, and California—have passed or advanced broad right‑to‑repair laws targeting consumer electronics. These laws typically require manufacturers to:

- Provide access to spare parts and tools at “fair and reasonable” prices.

- Publish repair manuals or service documentation.

- Offer software and firmware necessary for diagnostics and activation.

Federal agencies have joined in. In 2021, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) issued a landmark report, “Nixing the Fix”, criticizing many manufacturer‑imposed repair barriers as unsupported by safety or security evidence.

European Union: Repair as Climate Policy

The European Union has gone further by embedding repairability into its broader circular‑economy and climate frameworks. Under ecodesign and proposed “right‑to‑repair” rules, manufacturers may be required to:

- Provide spare parts for a minimum number of years (often 7–10) after a product is sold.

- Score products on repairability, durability, and disassembly.

- Ensure common failures (like batteries and displays) can be replaced without destroying the device.

This has direct consequences for smartphones, laptops, and major appliances, nudging companies toward modular construction and standardized fasteners instead of glue‑heavy designs.

Beyond Consumer Gadgets: Tractors, Medical Devices, and More

Right‑to‑repair rules are also emerging for:

- Farm equipment – Farmers have long complained that software locks prevent them from fixing tractors and harvesters, pushing them to authorized dealers.

- Medical technology – Hospitals seek faster, cheaper repair options for critical devices where downtime can be life‑threatening.

- Household appliances and HVAC – Policies aim to keep large devices in service for a decade or more.

Each enforcement action or new directive now sparks rapid coverage, expert commentary, and heated social‑media debates about innovation, safety, and costs.

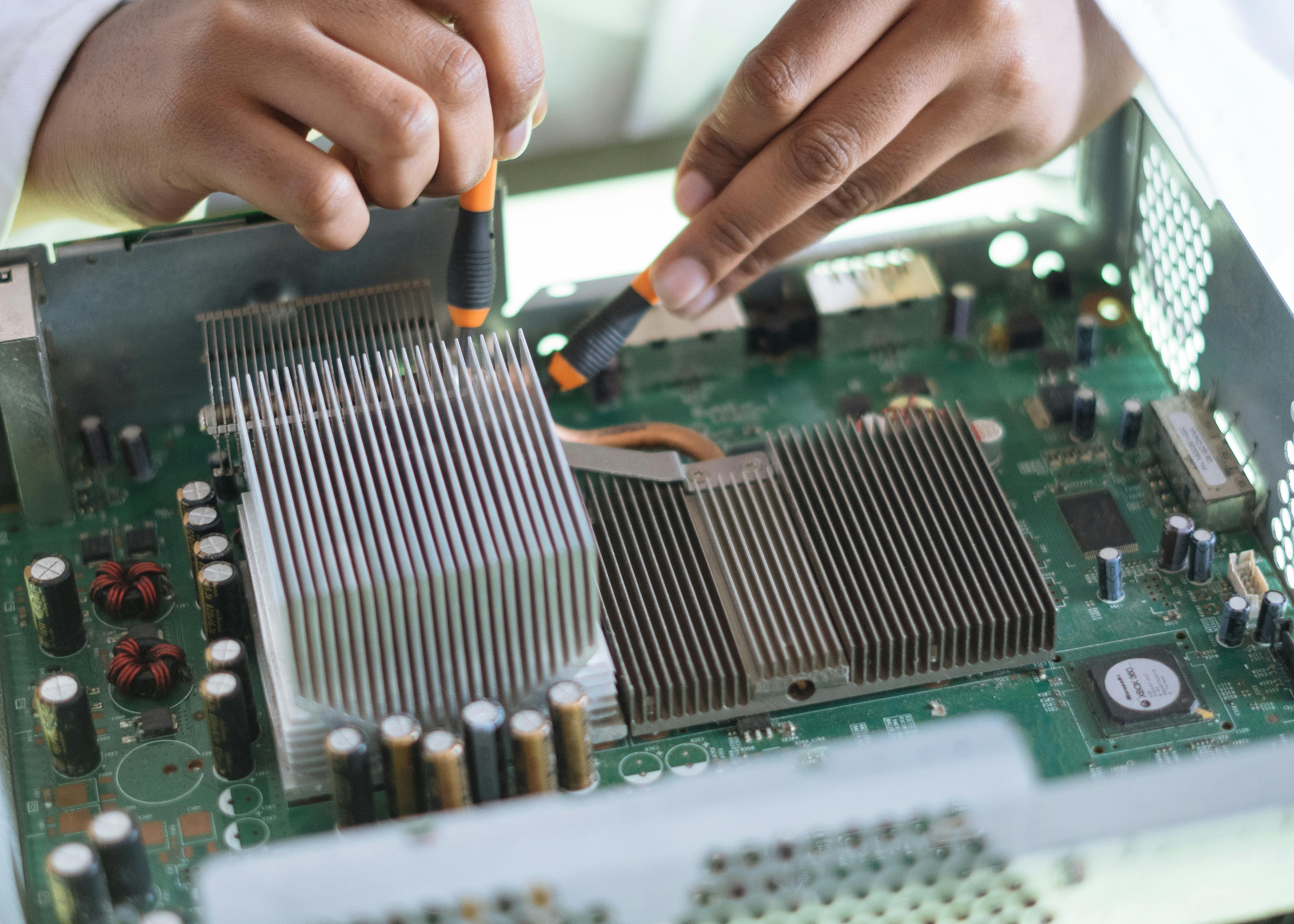

Figure 2: Laptop internals demonstrate how modular design can simplify repairs. Source: Pexels (CC0).

Technology: How Design Choices Make or Break Repairability

The right‑to‑repair battle is as much about physical and software architecture as it is about law. Teardowns by communities like iFixit and popular YouTube channels have turned internal layouts, adhesives, and chips into front‑page news.

Hardware Design: From Glued Slabs to Modular Systems

Key design features that shape repairability include:

- Batteries: Easily removable, standardized batteries dramatically improve device lifespan; permanently glued batteries do the opposite.

- Screws vs. Glue: Standard Phillips or Torx screws support disassembly; custom pentalobe or tri‑point screws and extensive adhesives impede it.

- Modularity: Swappable sub‑assemblies (camera modules, USB ports, speakers) allow quick fixes; tightly integrated boards often mean one small failure kills the entire device.

- Enclosure materials: Metal and well‑engineered plastics can be durable yet openable; fragile glass‑sandwich designs may be sleek but service‑hostile.

Some newer designs are beginning to reverse prior trends. Several major smartphone vendors have quietly re‑introduced easier battery replacement and fewer glued‑in components in response to political and consumer pressure.

Software Locks and Parts Pairing

Even when hardware is physically repairable, software can thwart fixes. A growing flashpoint is “parts pairing,” where a replacement screen, battery, camera, or logic board must be cryptographically or digitally authorized by the manufacturer.

Common manifestations include:

- Feature degradation – Replaced screens may lose True Tone, Face ID, or fingerprint unlock unless paired by the vendor.

- Warning messages – Persistent “non‑genuine part” warnings may scare users away from third‑party repairs.

- Hard locks – Certain components simply will not function without vendor software tools or online activation.

Manufacturers justify these choices as protecting security, safety, and user experience. Advocates counter that they also entrench monopoly control and can turn otherwise routine repairs into expensive, centralized services.

Diagnostics and Firmware

Access to diagnostics and firmware updates is another technical battleground:

- Independent shops often need official diagnostic suites to correctly calibrate sensors and biometric systems.

- Firmware region locks or throttling can limit the use of third‑party batteries or refurbished parts.

- Secure boot configurations may prevent loading alternative operating systems even when hardware remains functional.

“Security should not be a pretext for locking users out of their own devices.”

— Electronic Frontier Foundation, on right‑to‑repair and digital locks

Figure 3: E‑waste is one of the fastest‑growing waste streams globally. Extending device lifespans can substantially reduce emissions. Source: Pexels (CC0).

Scientific and Environmental Significance: Why Repair Beats Recycling

From a life‑cycle‑analysis (LCA) perspective, the most climate‑friendly device is often the one you already own. Numerous studies show that manufacturing a smartphone or laptop typically accounts for the majority of its lifetime carbon emissions—far more than its electricity use during everyday operation.

Embodied Carbon and Materials

Modern electronics embed:

- Energy‑intensive semiconductors and display panels.

- Critical raw materials like cobalt, lithium, rare earth elements, and gold.

- Complex multi‑layer PCBs and precision machining processes.

Scrapping a device early, even if it is recycled, typically recovers only a fraction of these inputs. Extending the lifespan by even 1–2 years can produce significant emissions savings per user, especially at the scale of hundreds of millions of devices.

Repair vs. Replacement: Quantifying Benefits

While exact figures vary by model and usage, analyses summarized by bodies like the European Commission and environmental NGOs indicate:

- Extending a smartphone’s use from 3 to 5 years can cut its annualized carbon footprint by 30–40%.

- Repairing a laptop instead of replacing it can avoid hundreds of kilograms of CO₂‑equivalent emissions over its extended lifetime.

- Widespread adoption of repair policies could reduce national e‑waste volumes by tens of thousands of tonnes per year.

This is why policymakers increasingly describe right‑to‑repair as both a consumer‑rights and climate‑action lever.

Socio‑Economic Science: Local Jobs and Resilience

There is also a socio‑economic dimension. Healthy repair ecosystems:

- Create local, service‑based jobs that are geographically distributed rather than concentrated in manufacturing hubs.

- Improve resilience by making communities less dependent on fragile global supply chains for new devices.

- Help bridge the digital divide by making refurbished devices more available and affordable.

“A society that can fix what it uses is inherently more resilient than one that must constantly buy new.”

— Paraphrasing themes from circular‑economy researchers and policy analysts

Recent Milestones: From Corporate Policies to Viral Teardowns

The last few years have seen a cascade of milestones that have pushed right‑to‑repair into mainstream discussion threads, front‑page headlines, and policy agendas.

Corporate Shifts and Self‑Service Repair Programs

Facing regulatory and reputational pressure, several major manufacturers have:

- Launched self‑service repair portals offering official parts, tools, and manuals to consumers.

- Partnered with third‑party repair chains to expand authorized service networks.

- Publicly committed to longer software and parts support windows for certain products.

Tech media routinely analyzes these moves, asking whether they truly expand consumer freedom or simply pre‑empt stronger legislation.

Teardowns and Social Media Momentum

On YouTube and TikTok, channels dedicated to:

- Device teardowns

- Board‑level repair

- Refurbishing and upcycling

have gained substantial followings. Viral videos often show:

- Seemingly “dead” phones revived with a cheap component swap.

- Laptops rescued by reflowing solder or replacing a few capacitors.

- Side‑by‑side comparisons of repairable vs. non‑repairable designs.

Influential creators highlight how small design decisions—like gluing in a battery instead of using a bracket—can determine whether a device is easily repaired or effectively disposable.

Grassroots and Policy‑Focused Coverage

On sites like Hacker News, right‑to‑repair threads routinely climb to the front page when new laws or corporate announcements drop. Discussion often centers on:

- Economic modeling of repair markets and monopoly power.

- Security implications of third‑party access to firmware and diagnostics.

- Legal nuances of copyright, circumvention, and warranty law.

Researchers, engineers, and lawyers use these forums to scrutinize the fine print between genuine reform and “checkbox compliance.”

Challenges: Security, Safety, and Competing Incentives

Despite growing support, right‑to‑repair faces several serious challenges. Some are technical; others are economic, legal, or cultural.

Manufacturer Concerns: Security and Liability

Manufacturers often raise three major arguments:

- Security risks – Opening systems to third‑party repair and diagnostics could, they argue, enable tampering with secure elements, payment systems, or biometric data.

- Safety and reliability – Poor‑quality parts or improper repairs might cause overheating, battery fires, or malfunction of safety‑critical features.

- Intellectual property – Detailed service manuals and diagnostic tools may reveal proprietary processes, making reverse engineering or cloning easier.

Policy discussions are increasingly focused on how to address these concerns without giving companies total control over the repair ecosystem.

Economic Incentives and Business Models

There are also structural incentives that push against repair:

- Planned obsolescence, whether intentional or not, can drive sales of new models.

- Service monopolies can be lucrative; restricting parts and tools protects high‑margin repair revenue.

- Complex design integration may lower manufacturing costs or enable thinner devices but also makes modularity harder.

Any serious right‑to‑repair framework must confront these economic realities, potentially by aligning profits with long‑term durability—through extended warranties, product‑as‑a‑service models, or design incentives.

Technical Complexity and Skill Gaps

Modern electronics are more technically complex than ever:

- High‑density boards and micro‑BGA packages require advanced tools and training.

- Multi‑layer PCBs and integrated SoCs make board‑level repair more challenging.

- Waterproof ratings and compact designs push tolerance limits, complicating disassembly.

This doesn’t make right‑to‑repair impossible, but it does mean that repair literacy, training programs, and accessible documentation are crucial to avoid unsafe or ineffective fixes.

Practical Tools for Consumers: Making Your Devices Last Longer

While policymakers and corporations negotiate the future, individual users can already extend device life significantly by combining better habits with the right tools.

Essential Repair and Maintenance Gear

A basic electronics toolkit can make common repairs and maintenance (like battery and SSD swaps) far more accessible. Popular options include:

- Precision screwdriver kits, such as the iFixit Morro 26‑bit Driver Kit , which covers most smartphone and laptop fasteners.

- Anti‑static work mats and wrist straps to prevent ESD damage to sensitive components.

- Spudgers and plastic opening picks for safely separating screens and housings without scratching or cracking them.

Data Hygiene and Software Care

Many “slow” devices are bottlenecked by software rather than hardware:

- Regularly remove bloatware and unused apps.

- Offload data to external drives or the cloud to free local storage.

- Keep firmware and OS updates current—within reason—to benefit from security patches without overloading older hardware.

Battery and Thermal Management

Batteries and thermals are often the first points of failure:

- Avoid chronic 0–100% charge cycles; partial cycles are gentler on lithium‑ion cells.

- Keep vents clear and periodically clean dust from fans and heat sinks.

- Use a quality laptop stand or cooling pad for heavy workloads to reduce heat stress.

Figure 4: DIY repair culture is fueled by online tutorials and communities sharing step‑by‑step guides. Source: Pexels (CC0).

DIY Culture and Knowledge Sharing: The Social Side of Repair

The explosion of online tutorials, forums, and teardown videos has turned repair from a niche skill into a widely shared hobby and side‑profession.

Communities and Learning Resources

Educated non‑specialists now routinely learn from:

- Step‑by‑step guides on platforms like iFixit.

- YouTube channels demonstrating board‑level diagnostics and microsoldering.

- Online courses covering electronics fundamentals and troubleshooting techniques.

These communities improve not only repair skills but also hardware literacy, helping consumers make better purchasing decisions and spot anti‑repair design patterns.

From Repair to Innovation

Interestingly, repair culture often overlaps with:

- Hardware hacking and modding—adding new features or improving performance.

- Upcycling and creative reuse—turning old devices into media centers, retro gaming rigs, or IoT nodes.

- Open‑hardware design—projects like Framework’s laptops or various open‑source handhelds.

In this way, right‑to‑repair not only extends device lifespans but also fuels experimentation and grassroots innovation.

Conclusion: Device Longevity as a Measure of Tech Maturity

The fight over right‑to‑repair is ultimately a fight over what mature, responsible technology looks like. In the early eras of consumer electronics, rapid obsolescence and sealed‑box designs were often accepted as the price of innovation. Today, with climate constraints tightening and digital infrastructure underpinning every aspect of life, that bargain is under intense scrutiny.

A more sustainable future for devices likely rests on a few key shifts:

- Embedding repairability and durability into design requirements, not as afterthoughts.

- Ensuring that security and safety are achieved through robust engineering, not vendor lock‑in.

- Aligning business models with long‑term support, upgradability, and refurbishment.

- Empowering users—with knowledge, tools, and legal rights—to steward the hardware they own.

As legislation evolves and corporate strategies adapt, consumer expectations are changing too. Increasingly, buyers ask not only “What can this device do?” but also “How long will it last—and who controls its future?” The answers to those questions will define the next decade of consumer technology.

Extra Value: How to Evaluate a Device’s Repairability Before You Buy

When shopping for your next phone, laptop, or appliance, you can already factor right‑to‑repair into your decision‑making. Consider the following checklist:

- Repairability scores – Look up independent ratings from organizations such as iFixit or, in some regions, official repairability labels.

- Parts availability – Check whether the manufacturer sells official replacement parts to consumers or independent shops.

- Service manuals – See if documentation is published openly or locked behind dealer portals.

- Battery design – Prefer devices with accessible, replaceable batteries over fully sealed ones.

- Upgrade paths – For laptops and desktops, prioritize models with upgradable RAM and storage.

- Support commitments – Review how many years of software updates and security patches are promised.

By rewarding manufacturers that prioritize repairability and longevity, consumers can amplify the regulatory and cultural shifts already underway—and help build a tech ecosystem where long‑lived, fixable devices are the norm rather than the exception.

References / Sources

Further reading and sources for concepts discussed in this article:

- FTC – “Nixing the Fix: An FTC Report to Congress on Repair Restrictions”

- iFixit – Right to Repair Overview

- The Verge – Right‑to‑Repair Coverage

- Wired – Right‑to‑Repair Articles

- Ars Technica – Gadgets & Right‑to‑Repair Reporting

- European Commission – Ecodesign and Sustainable Products Policies

- Electronic Frontier Foundation – Right‑to‑Repair Issue Page