Why David Mamet Thinks Robert Duvall Quietly Out-Acted Everyone

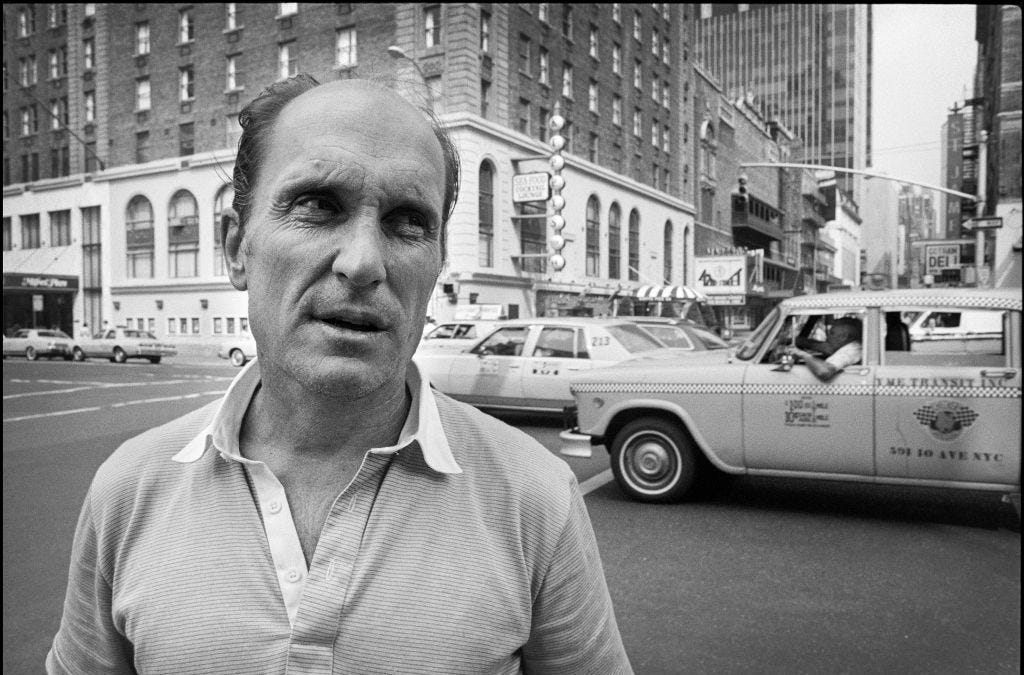

David Mamet’s recent essay in The Free Press, “Robert Duvall Was the Best Actor of His Generation,” isn’t just a farewell to a screen legend; it’s a compact history lesson in American acting. Through memories of American Buffalo and a half-century of collaboration and admiration, Mamet effectively asks a pointed question: how did an actor this definitive remain somehow underrated?

David Mamet on Robert Duvall: A Playwright Eulogizes His Ideal Actor

Mamet’s piece reads like a backstage conversation extended to the rest of us—part craft seminar, part cultural diagnosis. By tracking Duvall from the New York stage to the center of the New Hollywood era, he makes the case that Duvall’s greatness lies not in showy transformations, but in an almost stubborn normalcy that made everyone around him more believable.

From Neighborhood Playhouse to American Buffalo: The Context Behind the Tribute

Mamet opens by placing himself in the mid‑20th century New York acting world. As a student at the Neighborhood Playhouse, he was immersed in the Sanford Meisner school of performance—a sibling to Lee Strasberg’s Method. This is the ecosystem that produced actors like Robert Duvall, who blended discipline with a lived-in naturalism that never felt like “acting.”

By the time Duvall originated the lead role in Mamet’s American Buffalo in 1977, he was already a low-key icon: Tom Hagen in The Godfather, the mysterious Boo Radley in To Kill a Mockingbird, and the steel-nerved Lieutenant Kilgore in Apocalypse Now. Mamet is effectively saying: I wrote American Buffalo in the same universe where Duvall had already redefined what “supporting actor” even meant.

“Best of His Generation”: What Mamet Thinks Duvall Did Differently

Mamet doesn’t throw the phrase “best actor of his generation” around lightly. Coming from a writer famous for being prickly—even hostile—about contemporary acting, the praise is telling. For Mamet, Duvall represents acting as work, not mysticism: specific, repeatable choices instead of emotional strip-mining.

“He was the best actor of his generation, because he didn’t seem to be doing anything at all.”

That “doing nothing” is the key. Duvall’s performances rarely announce themselves the way Al Pacino’s or Jack Nicholson’s might. Instead, they pivot on micro-choices: a pause before a line, a half-smile that undercuts sentimentality, an almost bureaucratic calm in the middle of chaos. Tom Hagen in The Godfather is the perfect example—he’s surrounded by larger‑than‑life gangsters, and yet he’s the one you believe could walk into any room and get things done.

Mamet, whose own dialogue is famously rhythmic and stylized, clearly respects that Duvall never tried to “improve” the lines by overdressing them. He trusted that if he played the intention cleanly, the language would do the work.

Essential Robert Duvall Performances Mamet’s Praise Brings Back into Focus

Mamet’s essay foregrounds American Buffalo, but reading it in 2026 almost demands a rewatch of Duvall’s greatest hits. Together they form the argument Mamet is making: no one else covered this much ground with this much quiet authority.

- The Godfather (1972) – Tom Hagen

Duvall’s consigliere is the grown‑up in a movie of operatic emotions. His stillness is a choice, and it grounds the entire epic. - Apocalypse Now (1979) – Lt. Kilgore

The “smell of napalm” scene has been quoted into oblivion, but it’s the strange cheerfulness—Kilgore handing out hats like party favors—that makes it chilling. - Tender Mercies (1983) – Mac Sledge

The role that finally earned him an Oscar. It’s practically the anti‑Kilgore: all regret and gentleness, a fallen country singer trying to live small. - Lonesome Dove (1989) – Gus McCrae

On television, he turned a miniseries into an American myth, proving you didn’t need a big screen for big acting. - American Buffalo (1977 stage; later film adaptation)

Mamet’s own hustler antihero; hearing the playwright revisit this collaboration in 2026 effectively canonizes it.

Mamet’s Essay Style: A Curmudgeon Drops the Guard

Anyone who has followed David Mamet over the last decade knows he’s not shy about polemics. His public persona has increasingly been that of the cranky cultural contrarian. That’s what makes this piece on Duvall interesting: the argument is less about politics or “the culture” and more about professional respect.

His memories of the Neighborhood Playhouse, of Sanford Meisner, and of crafting American Buffalo location the essay in a broader lineage of American theater. That context matters. Mamet is effectively saying: whatever you think of the Method, whatever you think of acting theory, the proof is in the audience’s pulse. Duvall, for him, is where all the theory cashes out.

“He never explained. He never showed his work. He just did it, and the audience believed him.”

That line—about never “showing his work”—is as close as Mamet gets to a manifesto. He’s pushing back against an acting culture that sometimes prioritizes visible effort, elaborate preparation stories, and awards-season mythology. Duvall simply showed up and made things real.

What the Tribute Leaves Out: Weaknesses, Blind Spots, and the “Generation” Question

As persuasive as Mamet’s praise is, calling anyone “the best actor of his generation” invites questions. The same era gave us Pacino, De Niro, Gene Hackman, Dustin Hoffman, and, later, Meryl Streep and Jessica Lange. Mamet doesn’t really litigate the competition; he simply asserts Duvall’s supremacy.

That absolutism is both the strength and weakness of the piece. It’s emotionally satisfying, but it leaves little room to ask how gender, race, and casting norms of the time shaped who even got to be in the “best of his generation” conversation. This is a world where a certain kind of white, male, American intensity was the default definition of greatness.

The essay also doesn’t spend much time on Duvall’s misfires or lesser‑known late‑career work. For a tribute, that’s understandable; the genre leans toward highlight reels. But readers who only know Duvall from memes of Kilgore or the halo of The Godfather might come away without a sense of how uneven the industry could be, even for someone that talented.

Legacy, Influence, and Why Mamet’s Piece Matters Now

In 2026, revisiting Robert Duvall through Mamet’s eyes lands differently than it might have a decade ago. We’re in an era dominated by franchises, IP, and heavily mediated celebrity personas. Duvall, by contrast, felt almost defiantly uninterested in branding. His “brand,” if anything, was credibility—if he showed up, the movie or series immediately seemed more serious.

Mamet’s essay is really about that kind of legacy: not box-office dominance, not meme‑ability, but the way one performer can quietly raise the floor of realism across American film and television. It’s a reminder to look again at the performances that make a scene feel true without demanding applause.

As a piece of writing, Mamet’s tribute is compact, personal, and pointed. It doesn’t resolve the argument over who definitively owns the title of “best actor of his generation,” but it makes a strong case that if you’re drawing up a shortlist, leaving Robert Duvall off it says more about your film literacy than about his work.

For younger actors and film fans, the essay works as a curated watchlist prompt: go back, rewatch, and pay attention to the man who, in scene after scene, never seemed to be “doing anything” and yet changed what American acting looked like.

Where to Watch and Learn More About Robert Duvall

If Mamet’s essay has you ready for a deep dive, here are starting points that highlight both Duvall’s range and the critical conversation around him:

- Robert Duvall on IMDb – full filmography, awards, and credits.

- Robert Duvall interviews on YouTube – long-form conversations about his process.

- The Free Press – for Mamet’s full essay and other cultural commentary.

Many of his landmark performances rotate through major streaming services; checking your local availability for The Godfather, Tender Mercies, and Lonesome Dove is the most direct way to see, first-hand, what Mamet is talking about.