The Silent Spiral: A Mother’s Journey Through Her Daughter’s Eating Disorder and Back

By Adapted from a Slate health feature, summarized and explained

Topic: Recognizing and responding to eating disorders in teens and young adults.

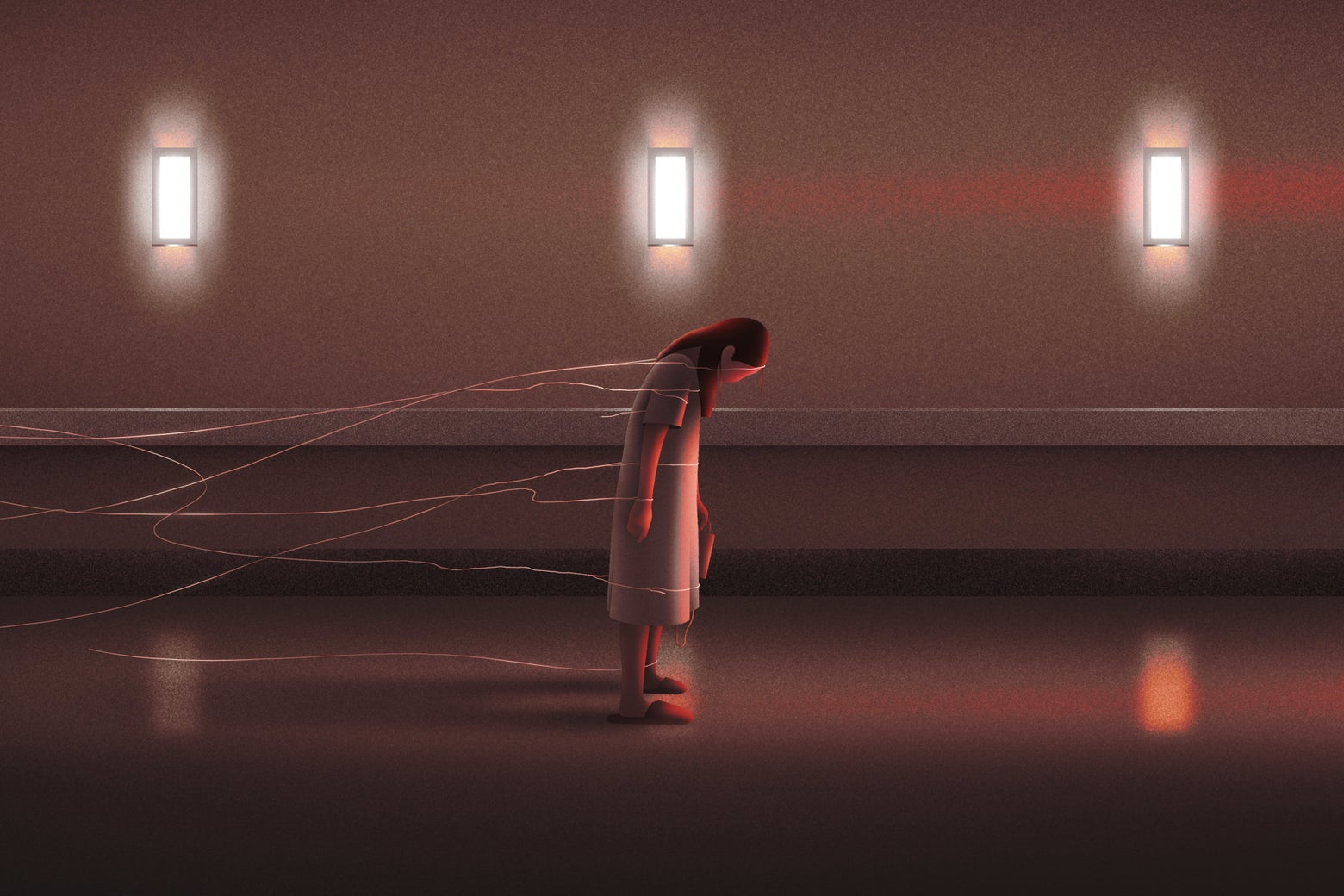

The mother who shared her story with Slate thought her daughter was just “being healthy.” A little more interest in nutrition, a new exercise habit, smaller portions at dinner—it all seemed reasonable. By the time she realized her daughter was in the grip of a life‑threatening eating disorder, the illness had taken over almost every part of the girl’s life.

If you’re a parent, caregiver, or someone who loves a teen or young adult, you may recognize pieces of this story—and you may also be unsure where “normal” ends and “dangerous” begins. This page walks through what was happening in that Slate story beneath the surface, what science tells us about eating disorders, and how you can respond early and effectively.

When “Healthy Habits” Become a Hidden Illness

Eating disorders are among the deadliest mental health conditions, second only to opioid overdose, according to research summarized by the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health. They are medical illnesses—not choices or phases—and they can affect people of any size, gender, race, or background.

In the Slate essay, the mother (who calls her daughter “Olivia”) describes nearly a year where her child:

- Lost weight steadily but “never looked sick enough” to trigger alarm.

- Became intensely focused on “clean eating” and exercise.

- Insisted everything was fine—even as her world quietly shrank around food and body image.

By the time Olivia’s parents could see the full picture, her heart rate and lab values were dangerously low, and rapid intervention was critical. This is painfully common: parents often blame themselves for “missing” signs, when in reality eating disorders are skilled at hiding in plain sight.

“Most families are doing their very best with the information they have. Eating disorders thrive in secrecy and ambiguity—that’s not a parent’s failure, it’s the nature of the illness.”

— Child and adolescent psychiatrist, eating disorders program (composite expert perspective)

Early Warning Signs Parents Often Miss

Many of Olivia’s early behaviors could easily be mistaken for positive lifestyle changes. What made them dangerous was the pattern, intensity, and what they were costing her physically, emotionally, and socially.

While every person is different, these clusters of signs deserve attention, especially in adolescents and college‑age young adults:

- Food and eating changes

- Cutting out entire food groups (carbs, fats, “processed foods”) seemingly overnight.

- Claiming new food allergies or intolerances that don’t match medical history.

- Preparing elaborate meals for others but eating very little themselves.

- Becoming distressed if “safe foods” aren’t available.

- Body and weight preoccupation

- Frequently checking mirrors, pinching body parts, or weighing themselves.

- Making negative comments about their body, even when others reassure them.

- Comparing their eating or body size to friends or influencers.

- Exercise and activity shifts

- Rigid exercise routines, with guilt or panic if a workout is missed.

- Exercising despite injuries, illness, or extreme fatigue.

- Mood, school, and social changes

- Pulling away from friends, family dinners, or events involving food.

- More irritability, anxiety, or perfectionism than usual.

- Drop in grades or obsession with “doing everything perfectly.”

- Physical red flags (especially when several occur together)

- Rapid or significant weight loss—or, in larger bodies, dramatic dieting changes even without visible weight loss.

- Feeling cold all the time, dizziness, fainting, or low energy.

- Changes in menstrual cycles or delayed puberty.

What Was Really Happening to Olivia’s Brain and Body

In the Slate story, the mother describes her daughter becoming “someone I didn’t recognize”—rigid, withdrawn, consumed by food rules. From a medical standpoint, several processes were likely interacting:

- Starvation effects: Prolonged restriction changes brain chemistry, increasing anxiety and preoccupation with food. Classic studies like the Minnesota Starvation Experiment showed that even healthy volunteers developed obsessional thinking around food and mood changes when underfed.

- Genetic and temperament factors: Many people with eating disorders share traits like perfectionism, sensitivity to criticism, and high anxiety. Research suggests a strong genetic component; environment and culture then shape how that vulnerability shows up.

- Social and cultural pressure: Social media filters, wellness culture, and diet talk at school can normalize extreme behaviors. Teens may genuinely see their actions as “disciplined” rather than dangerous.

By the time physical symptoms appear—like Olivia’s low heart rate and blood pressure—the illness is often severe. That’s why mental health and medical guidelines, including those from the Academy for Eating Disorders, emphasize early intervention before a crisis.

“Recovery is absolutely possible, especially when families are brought in as partners and treatment starts early. We treat this like the serious medical condition it is.”

— Pediatric eating disorder specialist (composite expert perspective)

Step‑by‑Step: What to Do If You’re Worried About Your Child

Reading Olivia’s story, many parents think, “This could be us.” If you have that gut feeling, it’s worth acting on it. Here’s a practical roadmap grounded in current best practices.

1. Start a calm, non‑judgmental conversation

Choose a neutral, relatively low‑stress moment. Aim for curiosity, not confrontation.

- Use “I” statements: “I’ve noticed you seem more anxious around meals, and I’m worried about you.”

- Avoid comments about weight or appearance (“You’re too thin”) and focus on health and happiness.

- Expect denial or minimization. That doesn’t mean you’re wrong; it’s part of the illness.

2. Schedule a medical evaluation—soon

Ask for an urgent visit with a pediatrician, family doctor, or adolescent medicine specialist and state clearly that you are concerned about a possible eating disorder.

- Bring a written list of behaviors and physical symptoms you’ve observed.

- Request vitals, blood work, and orthostatic measurements (heart rate and blood pressure lying vs. standing).

- If your concerns are dismissed, seek a second opinion—ideally from a clinician experienced in eating disorders.

3. Seek specialized mental health care

Evidence‑based treatments for youth include Family‑Based Treatment (FBT or the “Maudsley” approach), cognitive‑behavioral therapy for eating disorders (CBT‑E), and sometimes medication to manage co‑occurring anxiety or depression.

- Search for providers via organizations like the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) in the U.S. or your national equivalent.

- Ask explicitly: “What is your experience treating eating disorders in adolescents?”

- For severe medical instability, inpatient or residential treatment may be necessary for safety.

4. Be prepared to take a leadership role around food

In Olivia’s case, recovery started when her parents, guided by clinicians, took charge of meals again. This can feel extreme, but it’s often essential because a malnourished brain cannot reliably choose recovery.

- Structure three meals and 2–3 snacks each day, following your treatment team’s guidance.

- Stay present during and after meals to support and gently redirect disordered behaviors.

- Expect tears, anger, or bargaining. Hold boundaries with compassion: “I know this feels impossible, and I love you too much to let the illness win.”

Common Roadblocks (And How Families in Recovery Navigate Them)

The Slate mother’s account is honest about how hard the process was: arguments at the table, moments of doubt, frustration with the health‑care system. These challenges are normal—and survivable.

“They don’t look sick.”

Many clinicians still rely too heavily on appearance or BMI. If your child’s behaviors and health markers are concerning, advocate for further assessment. You’re not being overprotective—you’re responding to a genuine risk.

“I don’t want to ruin our relationship by pushing food.”

In the short term, refeeding can create conflict. Over time, many recovered young people—like the real‑world cases echoed in Olivia’s story—say their parents’ persistence saved their lives. You can be both firm and loving.

“We can’t access or afford specialized treatment.”

Barriers are real. Options to explore:

- University‑affiliated clinics or teaching hospitals, which sometimes offer lower‑cost care.

- Telehealth services with eating disorder specialists.

- Skills‑based books and workbooks based on FBT or CBT‑E, as adjuncts—not replacements—for professional care when possible.

Before and After: What Recovery Can Look Like (Without Sugarcoating)

The Slate essay ends not with a fairytale, but with something much more real: a daughter who is medically stable, back in school, enjoying pieces of her old life, and still working—day by day—on recovery. That’s what evidence‑based care aims for: safety, capacity, and a life larger than the illness.

Recovery is rarely a straight line. Slips and setbacks are common, especially during stress, transitions, or life changes. What matters is building:

- A strong support network (family, friends, clinicians).

- Skills to manage anxiety, perfectionism, and emotions without turning to restriction or other disordered behaviors.

- Regular medical and therapeutic follow‑up, especially in the first few years after weight restoration or major improvements.

Many people who recover go on to describe a deeper compassion for themselves and others, more flexible relationships with food and movement, and careers or passions that have nothing to do with their illness. That possibility is worth fighting for, even on the hardest days.

Moving From Fear to Action: Your Next Steps

If parts of Olivia’s story echo in your home, you are not alone, and you are not powerless. You may not be able to choose whether an eating disorder shows up in your child’s life—but you can choose how quickly and decisively you respond.

To summarize:

- Trust your instincts when you notice concerning patterns around food, exercise, and mood.

- Seek medical and mental health evaluations early, and advocate firmly if concerns are minimized.

- Be willing to take a leadership role, with support from evidence‑based treatment approaches.

- Remember that full, meaningful lives after eating disorders are possible—many families have walked this road ahead of you.

You don’t have to navigate this alone. Consider bookmarking or sharing this page with other caregivers, and use the resources below to take a concrete step today—whether that’s making a phone call, scheduling an appointment, or simply starting a compassionate conversation at your own kitchen table.

Helpful, evidence‑informed resources

- National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) – Screening tools, helplines, and treatment information.

- F.E.A.S.T. – Parent‑run organization supporting families of people with eating disorders.

- Academy for Eating Disorders – Professional organization with educational resources.

- Talk with your child’s primary‑care clinician or school counselor about local eating disorder programs and specialists.

Call to action: If you’re even slightly worried about a child or teen in your life, choose one small step you can take in the next 24 hours—make a call, send an email, or start a gentle conversation. Early action can quite literally save a life.