Multimessenger Astronomy: How Cosmic Cataclysms Are Rewriting Our Map of the Universe

Multimessenger astronomy is the practice of observing the same cosmic event using multiple “messengers”: electromagnetic radiation (from radio waves to gamma rays), gravitational waves, neutrinos, and—indirectly—cosmic rays. This approach has moved from theory to reality over the past decade, turning dramatic events such as black hole mergers and neutron star collisions into natural laboratories for testing general relativity, nuclear physics, and cosmology.

Instead of relying solely on light from telescopes, astronomers now combine time-stamped alerts from global networks of instruments. When a gravitational-wave detector registers a ripple in spacetime, radio and optical telescopes can rapidly pivot to catch the afterglow. When a high-energy neutrino is detected from the Antarctic ice, space-based gamma-ray observatories and large ground telescopes scour the sky for flares from active galaxies or explosive transients.

Mission Overview: What Is Multimessenger Astronomy?

In essence, multimessenger astronomy aims to:

- Identify and characterize cosmic cataclysms such as black hole mergers, neutron star mergers, and core-collapse supernovae.

- Trace the origin of the universe’s most energetic particles, including ultra-high-energy cosmic rays and high-energy neutrinos.

- Measure fundamental cosmological parameters, like the Hubble constant, using “standard sirens” from gravitational-wave events.

- Understand how and where heavy elements (beyond iron) are synthesized in violent astrophysical environments.

- Test general relativity and alternative gravity theories in the strong-field, high-velocity regime.

“The universe is talking to us in many different ways. Multimessenger astronomy is how we finally start listening to all of them at once.” — Adapted from outreach talks by members of the LIGO Scientific Collaboration.

The Four Key Cosmic Messengers

Each messenger carries complementary information about astrophysical phenomena. When combined, they provide a more complete and less ambiguous picture than any single channel alone.

1. Gravitational Waves

Gravitational waves are ripples in spacetime predicted by Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity and first directly detected in 2015 by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO). Today, the global network includes:

- LIGO in the United States (Hanford and Livingston sites).

- Virgo near Pisa, Italy.

- KAGRA, an underground, cryogenic detector in Japan.

These facilities have amassed catalogs of compact-object mergers: black hole–black hole, neutron star–neutron star, and mixed systems. Each event encodes:

- Masses and spins of the merging objects.

- Luminosity distance (how far away the event is).

- Waveform morphology, sensitive to orbital dynamics and tidal effects.

Some detected black holes are unexpectedly massive or asymmetric, challenging models of stellar evolution and binary formation. This has sparked discussion of exotic formation channels, including:

- Dynamical formation in dense star clusters.

- Hierarchical mergers in galactic nuclei.

- Primordial black holes, though still speculative.

2. Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs)

Fast radio bursts are millisecond-long flashes of radio waves originating from distant galaxies. Since their discovery in 2007, FRBs have defied complete explanation, though magnetars—highly magnetized neutron stars—are leading candidates for at least some populations.

New facilities such as the Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment (CHIME), ASKAP in Australia, and MeerKAT in South Africa are detecting FRBs at a rapidly increasing pace, allowing:

- Statistical population studies, including repeaters versus apparent one-off events.

- Host-galaxy identification, tying FRBs to specific galactic environments.

- Dispersion measure analysis, using FRBs as probes of intergalactic plasma and the “missing baryons.”

3. High-Energy Neutrinos

Neutrinos are nearly massless, weakly interacting particles that can travel vast distances through matter and radiation fields almost unimpeded. High-energy neutrinos observed by the IceCube Neutrino Observatory at the South Pole have been associated with astrophysical accelerators such as blazars—active galactic nuclei whose jets are directed toward Earth.

When a neutrino’s reconstructed direction aligns with a flaring gamma-ray source, it offers compelling evidence that hadronic processes are at work, linking neutrinos to the origin of cosmic rays. IceCube’s detection of neutrino events correlated with the blazar TXS 0506+056 was a milestone in this effort.

4. Electromagnetic Radiation Across the Spectrum

Traditional astronomy—optical, radio, infrared, X-ray, and gamma-ray—remains crucial. Telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope, the Chandra X-ray Observatory, and large ground-based facilities (VLT, Keck, Subaru, Gemini) capture:

- Afterglows of neutron star mergers and gamma-ray bursts.

- Host-galaxy properties and local environments of FRBs.

- Long-term variability of blazars and other active galaxies.

The synergy comes when gravitational-wave and neutrino alerts trigger rapid follow-up observations, transforming brief, rare events into well-characterized transients.

Technology: How We Listen to the Violent Universe

Multimessenger astronomy depends on extreme-precision instrumentation, real-time data pipelines, and global coordination. Recent upgrades and new facilities are dramatically increasing both the quantity and quality of detections.

Gravitational-Wave Detectors: LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA

Advanced LIGO and Virgo use kilometer-scale laser interferometers to measure length changes far smaller than a proton’s diameter. Key technological elements include:

- High-power, ultra-stable lasers to reduce shot noise.

- Suspended mirrors with exquisite seismic isolation.

- Quantum squeezing techniques to reduce quantum noise in specific frequency bands.

Each observing run incorporates sensitivity improvements—better coatings, upgraded suspensions, improved control systems—boosting the volume of space surveyed and hence the detection rate. KAGRA adds an underground, cryogenically cooled interferometer designed to suppress thermal noise.

Radio Arrays and FRB Surveys

Modern radio facilities responsible for FRB discoveries and characterizations employ:

- Phased-array feeds to cover large areas of sky.

- Real-time signal processing to identify millisecond bursts.

- Automated localization pipelines that tie bursts to host galaxies using interferometric imaging.

This combination enables near-continuous sky monitoring and rapid alert generation.

Neutrino Telescopes

IceCube instruments a cubic kilometer of Antarctic ice with thousands of optical sensors. When a high-energy neutrino interacts with the ice, it produces charged particles that emit Cherenkov light, allowing reconstruction of:

- Arrival direction (with degree-scale precision for track-like events).

- Approximate energy (ranging from tens of GeV to beyond PeV).

Future projects like IceCube-Gen2 and KM3NeT in the Mediterranean aim to extend sensitivity and sky coverage.

Data Infrastructure and Alert Networks

The real power of multimessenger astronomy lies in rapid, interoperable data sharing. Systems like the Gamma-ray Coordinates Network (GCN) and its modern successors distribute:

- Time-stamped alerts for gravitational-wave triggers, neutrino detections, FRBs, and gamma-ray bursts.

- Sky localization maps (probability contours on the sky) to guide follow-up telescopes.

- Machine-readable event metadata, enabling automated scheduling by robotic telescopes.

“In a true multimessenger era, coordination and open data are as important as the detectors themselves.” — NASA GCN program documentation (paraphrased).

Scientific Significance: From Heavy Elements to Cosmic Expansion

Multimessenger astronomy is not just about more data; it is about qualitatively new constraints on fundamental questions in astrophysics and cosmology.

GW170817: A Rosetta Stone for Cosmic Cataclysms

The 2017 detection of GW170817—a binary neutron star merger—was a watershed moment. LIGO and Virgo observed the gravitational waves, while gamma-ray observatories detected a short gamma-ray burst just 1.7 seconds later. Over subsequent days and weeks, telescopes across the spectrum followed a rich electromagnetic afterglow.

This single event demonstrated that:

- Neutron star mergers are sites of r-process nucleosynthesis, forging elements like gold, platinum, and uranium.

- The merger produced a kilonova, whose spectral evolution mapped the production of heavy elements.

- Gravitational-wave distances can be combined with host-galaxy redshifts to yield an independent measurement of the Hubble constant—a “standard siren.”

Follow-up events and candidate counterparts have refined estimates of how common such mergers are and how much heavy material they eject into space.

FRBs as Cosmological Probes

By measuring how much an FRB’s signal is dispersed (high-frequency waves arrive earlier than low-frequency ones), astronomers estimate the total column of free electrons between Earth and the source. This allows:

- Mapping the distribution of ionized baryons in the cosmic web.

- Constraining feedback processes in galaxies and clusters.

- Potentially cross-checking constraints on dark energy and large-scale structure growth.

As FRB samples grow into the tens of thousands, statistical cosmology with FRBs could complement Type Ia supernovae and baryon acoustic oscillations.

Neutrinos and the Origin of Cosmic Rays

High-energy neutrinos carry information about hadronic acceleration in extreme environments—places where protons and heavier nuclei are pushed to energies unattainable in terrestrial accelerators. Multimessenger detections linking neutrinos to blazars or tidal disruption events help:

- Identify the long-sought astrophysical sources of ultra-high-energy cosmic rays.

- Distinguish hadronic from leptonic emission models in active galaxies.

- Probe particle interactions at energies beyond current collider capabilities.

Hubble Tension and New Physics

One of the hottest topics in cosmology is the “Hubble tension”: the mismatch between the expansion rate inferred from early-universe measurements (cosmic microwave background) and local distance ladders (supernovae, Cepheids). Gravitational-wave standard sirens provide an alternate route that is:

- Geometric (no need for a distance ladder).

- Independent of many systematics affecting traditional methods.

As catalogs of well-localized mergers grow, multimessenger measurements will either alleviate or exacerbate the tension—pointing toward refined astrophysics or genuinely new physics such as evolving dark energy or modifications of gravity.

Milestones: Key Discoveries in the Multimessenger Era

Within just a decade, multimessenger astronomy has progressed from a proof of concept to a routine, though still thrilling, part of observational astrophysics.

Selected Milestones

- 2015 – First direct detection of gravitational waves (GW150914), revealing a binary black hole merger.

- 2017 – GW170817: first binary neutron star merger with electromagnetic counterpart (kilonova and short GRB).

- 2017–2018 – Association of a high-energy neutrino with blazar TXS 0506+056 by IceCube and gamma-ray telescopes.

- 2018–2024 – Explosion in FRB detections; localization of repeating FRBs to specific host galaxies and environments.

- Ongoing – Progressive observing runs (O3, O4, and beyond) of LIGO–Virgo–KAGRA with steadily improving sensitivity.

“Multimessenger astronomy has transformed rare cosmic catastrophes into precision tools for exploring gravity, matter, and the shape of the universe.” — Summary adapted from NASA Astrophysics Division materials.

Challenges: From Localization to Data Deluge

Despite impressive progress, multimessenger astronomy faces technical, logistical, and theoretical hurdles.

Localization and Follow-Up

Gravitational-wave and neutrino detectors often provide relatively coarse sky maps. Early events had localization regions spanning hundreds of square degrees. Although techniques and detector networks have improved, challenges remain:

- Rapid tiling of large sky areas with optical and radio telescopes.

- Filtering contaminants such as unrelated supernovae or variable stars.

- Coordinating time zones and weather across global observatories.

Data Volume and Real-Time Analytics

Modern surveys generate petabyte-scale data streams. Extracting transient events within seconds requires:

- High-performance computing clusters and GPU-accelerated pipelines.

- Machine learning for anomaly detection and classification.

- Standardized data formats and open APIs for cross-facility integration.

The upcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) will amplify both the opportunities and the data-management challenges for multimessenger science.

Theoretical Uncertainties

To interpret multimessenger signals, astrophysicists must model:

- Relativistic magnetohydrodynamics in extreme magnetic fields and densities.

- Nuclear reaction networks for r-process nucleosynthesis.

- Jet launching and propagation in dense, anisotropic media.

These simulations are computationally intensive and sensitive to uncertain microphysics, such as the equation of state of ultra-dense nuclear matter inside neutron stars.

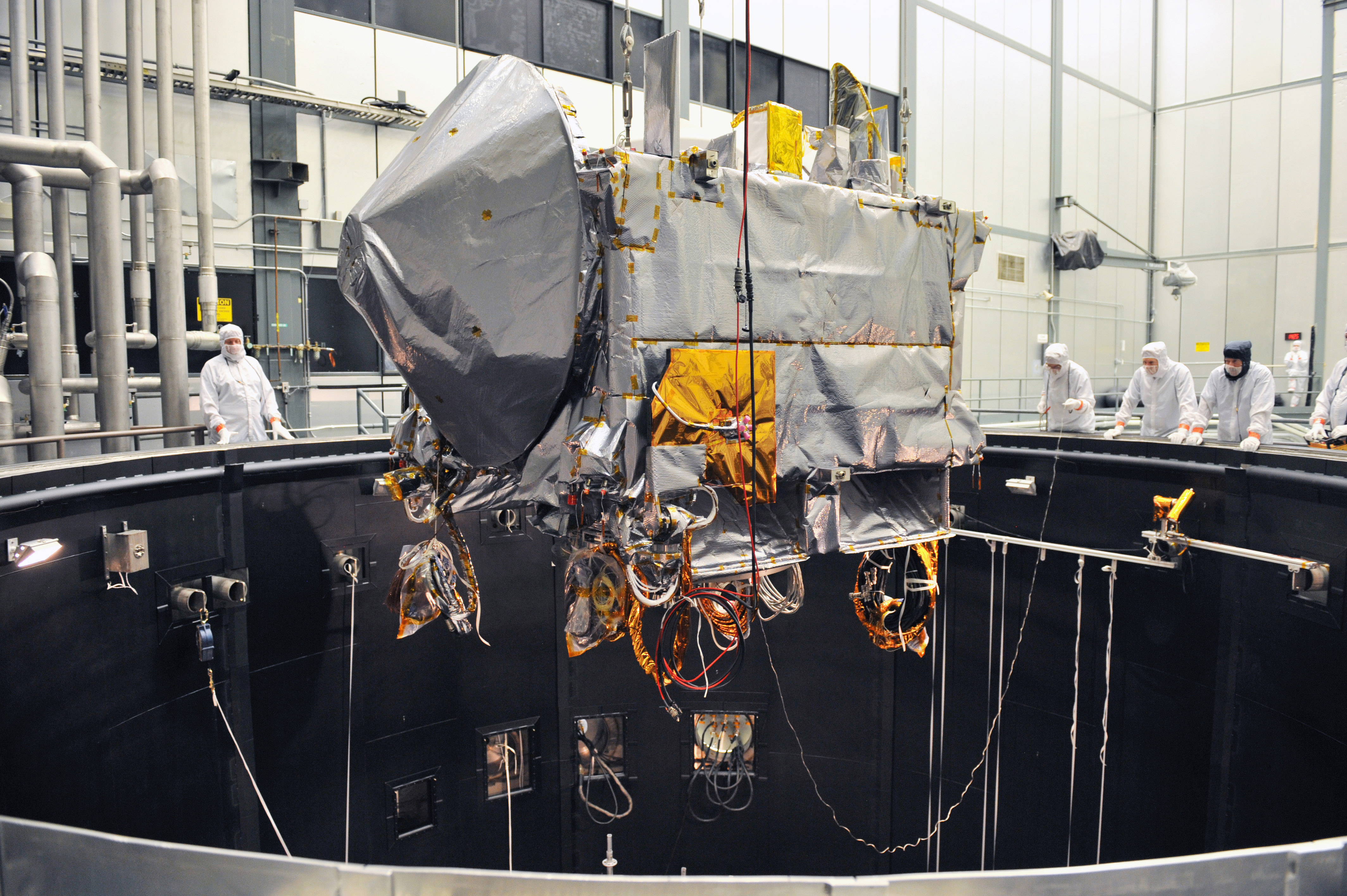

Visualizing the Multimessenger Universe

The following high-quality, royalty-free images provide visual context for key instruments and phenomena in multimessenger astronomy. All images are from NASA or other reputable, public-domain or permissively licensed sources.

Tools for Enthusiasts and Students

While professional multimessenger observatories are billion-dollar facilities, interested readers, students, and hobbyists can deepen their understanding and even contribute to related science using accessible tools.

Educational and Observational Resources

- LIGO Open Science Center provides real gravitational-wave data and tutorials suitable for advanced high-school and university students.

- Citizen-science platforms like Zooniverse host projects related to transient detection, galaxy morphology, and more.

- The IceCube Neutrino Observatory offers outreach materials and data sets for educational use.

Amazon Picks for Learning Astrophysics at Home

For readers who want structured, in-depth background in modern astrophysics and cosmology, a few widely recommended books and tools stand out:

- An Introduction to Modern Astrophysics (Carroll & Ostlie) – a comprehensive, university-level textbook often used in astrophysics programs.

- Just Six Numbers: The Deep Forces that Shape the Universe (Martin Rees) – a readable exploration of cosmological parameters and their implications.

- NightWatch: A Practical Guide to Viewing the Universe (Terence Dickinson) – an accessible guide for backyard astronomy, ideal for connecting sky maps to active research topics.

Why Multimessenger Astronomy Is Trending Now

Beyond the scientific breakthroughs, several factors make multimessenger astronomy particularly visible in popular culture and online media.

Instrument Upgrades and Detection Rates

Successive upgrades to gravitational-wave detectors, new FRB surveys, and expanding neutrino arrays translate directly into:

- More frequent detections, sometimes several per week in ongoing observing runs.

- Higher signal-to-noise ratios, allowing finer parameter estimation.

- Better sky localization, which improves the odds of catching electromagnetic counterparts.

Compelling Narratives and Media

Stories about “colliding black holes,” “cosmic fireworks,” and “signals from billions of years ago” make for inherently shareable content. Science communicators on YouTube, TikTok, and X (Twitter) have capitalized on:

- Animations that visualize spacetime ripples and mergers.

- Short explainers linking events like GW170817 to the gold in wedding rings.

- Live streams from observatories discussing new alerts and candidate events.

High-profile communicators and researchers, such as Katie Mack and Ben Deverett (among many others), regularly discuss gravitational waves, FRBs, and cosmology for broad audiences.

Cosmological Tension and Theoretical Stakes

The Hubble tension and open questions about dark energy, dark matter, and modified gravity raise the stakes of each new measurement. Multimessenger data sets allow theorists to:

- Test whether gravity behaves as expected over gigaparsec scales.

- Search for hints of evolving dark energy or exotic fields.

- Constrain models of early-universe physics via their impact on structure formation.

The Road Ahead: Next-Generation Observatories

Over the next decade, multimessenger astronomy will be transformed by new facilities with greater sensitivity, broader coverage, and improved coordination.

Space-Based Gravitational-Wave Astronomy

The European Space Agency’s Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), planned for the 2030s, will probe low-frequency gravitational waves from:

- Supermassive black hole mergers in the centers of galaxies.

- Extreme mass-ratio inspirals—stellar-mass objects orbiting supermassive black holes.

- Compact binaries within the Milky Way.

These signals will open a complementary window on galaxy assembly and black hole growth.

Next-Generation Ground-Based Detectors

Concepts like the Einstein Telescope in Europe and the U.S. Cosmic Explorer would extend the reach of terrestrial gravitational-wave observatories to much higher redshifts, turning compact-object mergers into high-statistics cosmological probes.

Expanded Neutrino and Radio Networks

Future neutrino telescopes (IceCube-Gen2, KM3NeT, Baikal-GVD) and radio arrays (the Square Kilometre Array, SKA) will:

- Greatly increase the sample of astrophysical neutrinos with well-constrained origins.

- Enable precision FRB localization and polarization studies across cosmic time.

- Provide continuous, deep monitoring of transient-rich regions of the sky.

Conclusion: A New Language for Cosmic Cataclysms

Multimessenger astronomy is, in effect, teaching us a new language for describing the universe. Where once we inferred the properties of black holes, neutron stars, and cosmic expansion from light alone, we now listen to the subtle tremor of spacetime, the whisper of neutrinos, and the crackle of fast radio bursts.

As detector sensitivities improve and networks expand, events that were once “once-in-a-lifetime” will become common. Each detection adds another point in a growing parameter space, enabling statistical studies of binary evolution, element synthesis, and cosmic acceleration. At the same time, outliers—particularly massive black holes, unusual FRB hosts, or unexpected neutrino associations—may point to genuinely new physics.

For students, researchers, and the scientifically curious public, this is an exceptional moment. Multimessenger astronomy sits at the nexus of astrophysics, cosmology, particle physics, and data science. Its progress depends not only on giant instruments but also on open data, robust software, and a global community of observers and theorists working in concert to decode the universe’s most violent, illuminating events.

Additional Resources and Further Reading

To explore multimessenger astronomy in more detail, the following resources provide accessible introductions, technical reviews, and up-to-date news.

Introductory Videos and Talks

- “How LIGO Detected Gravitational Waves” – Caltech / LIGO explainer.

- “The Most Powerful Explosions in the Universe” – PBS Space Time episode on neutron star mergers and kilonovae.

- “Neutrino Astronomy” – IceCube outreach talk.

Professional and Review Articles

References / Sources

Selected reputable sources for the information discussed in this article: