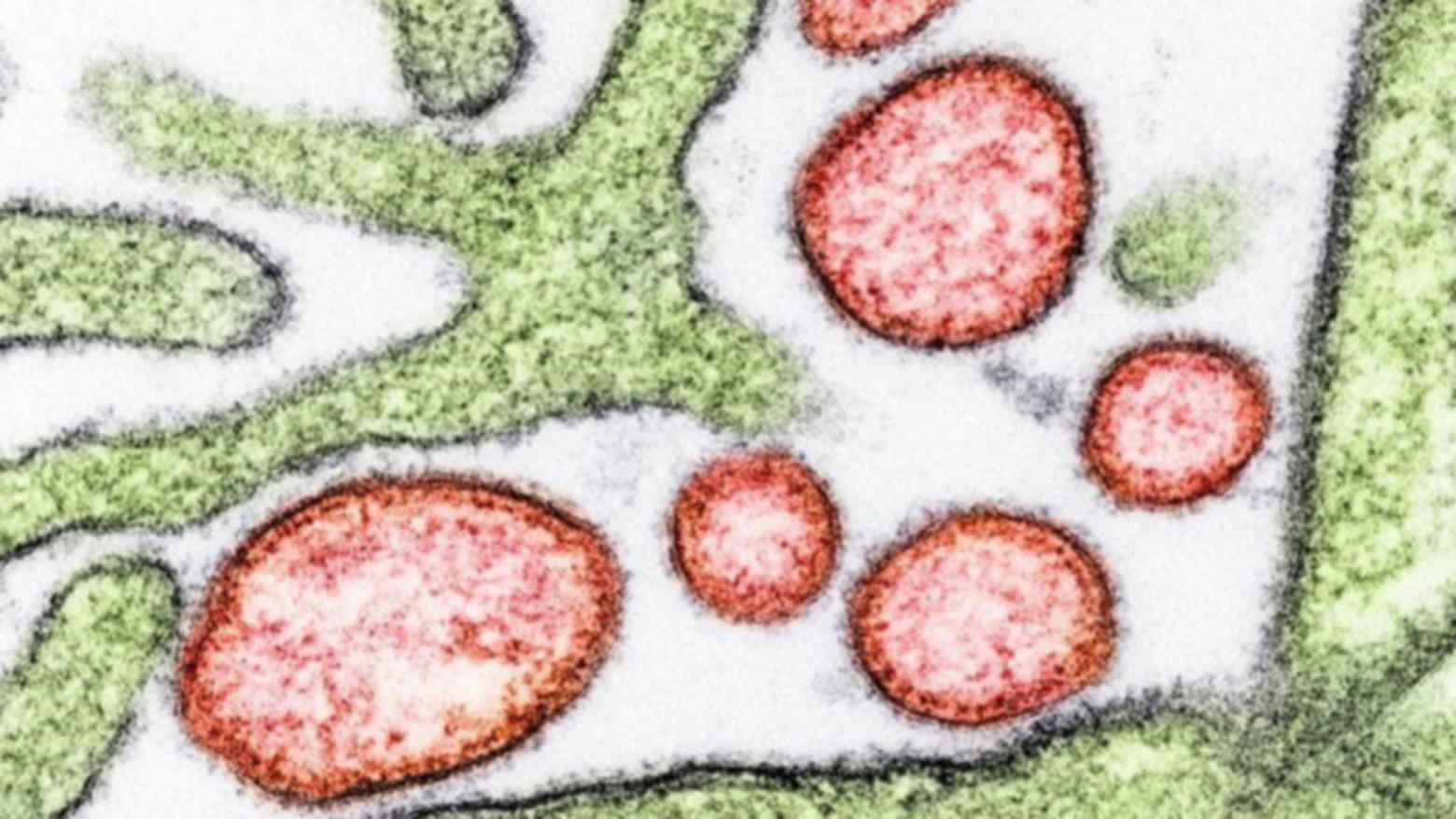

Breakthrough Nipah Virus Vaccine Enters Human Trials: What This Means for Global Health

Not many people have heard of Nipah virus, but for those living in parts of South and Southeast Asia, it’s a quiet, ever-present fear. Outbreaks are often small, but when they happen, they can be devastating—fatality rates have ranged from 40% to 75%, and there are no widely available treatments or vaccines yet.

That’s why the news that a first-in-human Nipah virus vaccine trial is starting is such an important milestone. It doesn’t mean the problem is solved overnight, but it does mark a genuine turning point in how we might protect people from this deadly disease in the future.

In this article, we’ll walk through what Nipah virus is, why this new vaccine matters, what clinical trials actually involve, and what everyday people—especially in affected regions—can realistically do right now to stay safer.

Understanding Nipah Virus: A Highly Fatal Zoonotic Threat

Nipah virus (NiV) is a zoonotic virus, meaning it jumps from animals to humans. Fruit bats (flying foxes) are its natural reservoir. People can become infected through:

- Consuming fruit or raw date palm sap contaminated by bats

- Close contact with infected animals (such as pigs)

- Close contact with infected people or their bodily fluids

Symptoms can range from mild flu-like illness to severe brain infection (encephalitis) and respiratory distress. Because it can spread between people in close contact and has such a high fatality rate, the World Health Organization (WHO) classifies Nipah as a priority pathogen for research and preparedness.

Recent Mini-Outbreaks Highlight the Ongoing Risk

In January 2026, India reported a “mini-outbreak” of Nipah virus, with rapid public health action helping to contain its spread. While the number of cases was limited, events like this demonstrate how quickly Nipah can emerge and the pressure it puts on local health systems.

“Nipah is the kind of virus that keeps epidemiologists up at night: high fatality, potential for human-to-human transmission, and no widely available countermeasures—yet.”

— Infectious disease specialist quoted in regional public health briefings

These flare-ups are a reminder that even if a disease doesn’t dominate global headlines, it can still be a serious local and regional threat, particularly in communities where people depend on seasonal fruit collection or palm sap harvesting for their livelihoods.

The First Nipah Vaccine Enters Clinical Trials

The promising news is that a first Nipah virus vaccine candidate has moved into human clinical trials. While specific trial details differ by sponsor and country, the overall goal is to determine whether the vaccine is safe and whether it triggers a protective immune response.

Many current Nipah vaccine candidates are based on platforms similar to those used for other viral diseases—such as viral vectors or protein subunits—that have been studied for years. Preclinical data in animal models have generally shown strong immune responses, which helped justify moving into human trials.

How Clinical Trials Work: From First Doses to Real-World Protection

It’s natural to wonder how soon a Nipah vaccine could be available. The honest answer is that it depends on how the trials go. Typically, vaccine development goes through several phases:

- Phase 1: Dozens of healthy volunteers receive the vaccine. Main goals: safety, side effects, and basic immune response.

- Phase 2: Hundreds of participants. Researchers refine dosing, continue safety monitoring, and assess how robust the immune response is.

- Phase 3: Hundreds to thousands, often in areas where the virus is a risk. The key question: Does the vaccine actually prevent disease?

- Regulatory review & rollout: If results are positive, national and international authorities review the data and decide on approval and recommendations.

For a disease like Nipah, where outbreaks are sporadic, trials can be logistically challenging. Researchers may use innovative trial designs, partner closely with local health systems, and sometimes rely on immune “correlates of protection” (lab markers that predict protection) when case numbers are low.

What This Breakthrough Means for People in At-Risk Regions

For communities in parts of India, Bangladesh, and neighboring countries, the potential of a Nipah vaccine offers cautious hope. Even if the vaccine is still years away from broad use, it signals that the world is taking this virus seriously.

- Improved outbreak readiness: Ongoing research often brings better surveillance, quicker testing, and improved community awareness.

- Stronger health systems: Investments in laboratories, cold chain, and training for trials can strengthen local capacity for other health threats too.

- Long-term prevention: If trials succeed, high-risk groups—such as healthcare workers and communities in recurring hotspot areas—may eventually have access to targeted vaccination.

“We shouldn’t oversell early-stage trials, but we also shouldn’t underestimate what they represent: a shift from reacting to Nipah outbreaks to potentially preventing them.”

— Public health researcher working on emerging infections

Practical Steps to Reduce Nipah Virus Risk Right Now

While vaccines are in development, everyday behaviors still matter. Public health agencies in affected regions recommend several practical steps:

- Avoid raw date palm sap: Bats can contaminate open containers. Boiling sap before consumption greatly reduces risk.

- Wash and peel fruit: Especially fruit that may have been partially eaten or exposed to bat droppings in orchards or near trees.

- Practice careful hygiene around sick people: Use masks if possible, wash hands frequently, and avoid direct contact with bodily fluids.

- Follow local health advisories: During an outbreak, authorities may temporarily restrict certain foods or activities to limit exposure.

- Protect healthcare workers: Use appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) and infection control protocols in clinical settings.

At a Glance: Nipah Virus and the Emerging Vaccine (Infographic)

Here is a text-based overview of the key points you might see in an infographic, designed to be accessible and screen-reader friendly:

- Fatality rate: Historically 40–75% in documented outbreaks.

- Reservoir: Fruit bats (flying foxes); spillover to pigs and humans.

- Transmission: Contaminated food, close contact with infected animals or people.

- Current treatment: Supportive care only; no specific antiviral widely recommended.

- Vaccine status: First human clinical trials underway; more candidates in preclinical pipelines.

- Key prevention now: Safe food practices, hygiene, and rapid outbreak response.

What the Science Says: Evidence and Ongoing Research

Over the past two decades, research groups and global health organizations have steadily built the evidence base around Nipah virus. Key findings include:

- Animal models: Studies in animals have shown that several vaccine approaches can produce strong neutralizing antibodies and protect against lethal challenges.

- Spillover drivers: Environmental changes, land use, and human encroachment into bat habitats increase the chances of spillover events.

- One Health approach: Effective control requires integrating human, animal, and environmental health strategies, reflecting how closely connected these systems are.

While detailed trial results will take time, the move into human testing would not have happened without promising safety and immune-response data from earlier work. Global health coalitions and national institutes continue to track progress and share findings openly to accelerate safe, evidence-based solutions.

Real-World Barriers: Access, Equity, and Trust

Even if a Nipah vaccine proves effective, getting it to the people who need it most will require more than good science. Common challenges include:

- Cost and supply: Ensuring vaccines are affordable and available in low- and middle-income countries.

- Logistics: Maintaining cold chains and reaching remote communities.

- Community trust: Addressing fears or misinformation through respectful, culturally appropriate communication.

Health workers and community leaders often play a crucial role in bridging these gaps, answering questions honestly and helping people weigh benefits and risks based on the best available evidence.

Looking Ahead: Hope with Honesty

The start of clinical trials for a Nipah virus vaccine is a genuine step forward. It doesn’t erase the risk overnight, and it doesn’t guarantee a successful product—but it does mean that for the first time, we are seriously testing a tool that could one day shift Nipah from a deadly threat to a preventable disease.

If you live in or care about affected regions, the most empowering things you can do right now are:

- Stay informed through reliable, science-based sources.

- Follow local public health guidance during outbreaks.

- Support or participate in research and community education efforts when it’s safe and appropriate.

Step by step, research, community action, and global cooperation are moving us toward a future where viruses like Nipah are far less frightening. For now, cautious optimism—grounded in evidence and practical prevention—remains our best guide.