Are We Seeing Alien Air? JWST, Exoplanet Biosignatures, and the New Hunt for Life

Exoplanet biosignatures sit at the intersection of astronomy, planetary science, atmospheric chemistry, and biology. With JWST already reshaping exoplanet science and future telescopes poised to push even further, we are entering the first era where “Are we alone?” can be approached as an observational question rather than pure speculation.

Online, every new JWST exoplanet paper triggers detailed YouTube explainers, long Twitter/X threads from astronomers, and TikTok visualizations of light curves and spectra. Behind the social-media buzz is a serious scientific effort to define, detect, and interpret the chemical fingerprints of life on distant worlds.

Mission Overview: How JWST and Next‑Gen Telescopes Hunt for Biosignatures

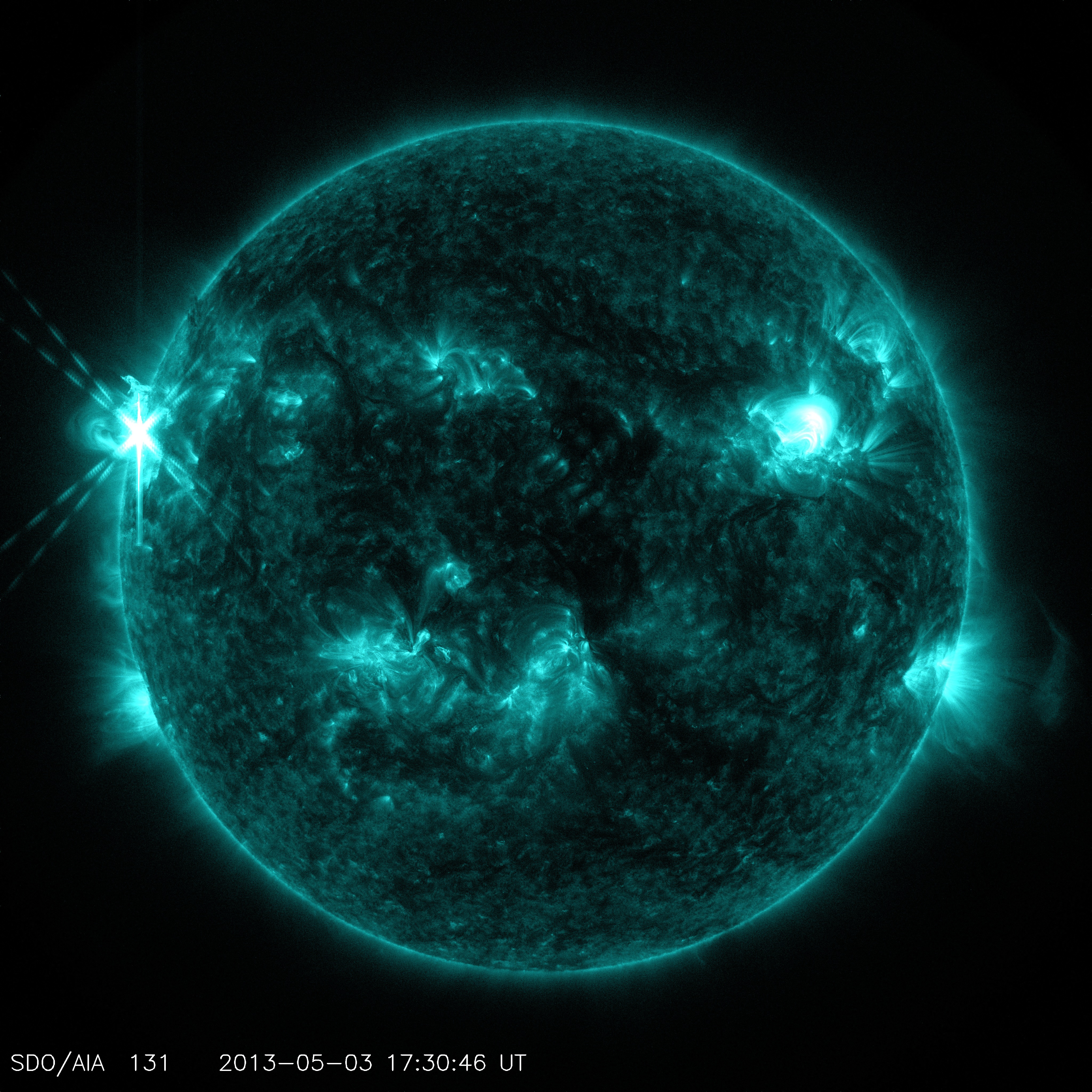

JWST was not designed exclusively as a “life-finding” telescope, but its infrared sensitivity and stability make it the most powerful exoplanet observatory currently in operation. Its instruments—primarily NIRSpec, NIRISS, and MIRI—allow astronomers to dissect the light from stars and planets with unprecedented precision.

Three Main Observing Modes for Exoplanets

Transit (Transmission) Spectroscopy

When a planet passes in front of its star, a tiny fraction of starlight filters through the planet’s atmosphere. Molecules in that atmosphere absorb specific wavelengths, imprinting their “barcodes” on the spectrum.Eclipse and Phase-Curve Spectroscopy

When the planet passes behind the star or shows different phases, JWST can isolate the planet’s thermal emission and reflected light, probing temperature structure and cloud coverage.Direct Imaging (Future Missions)

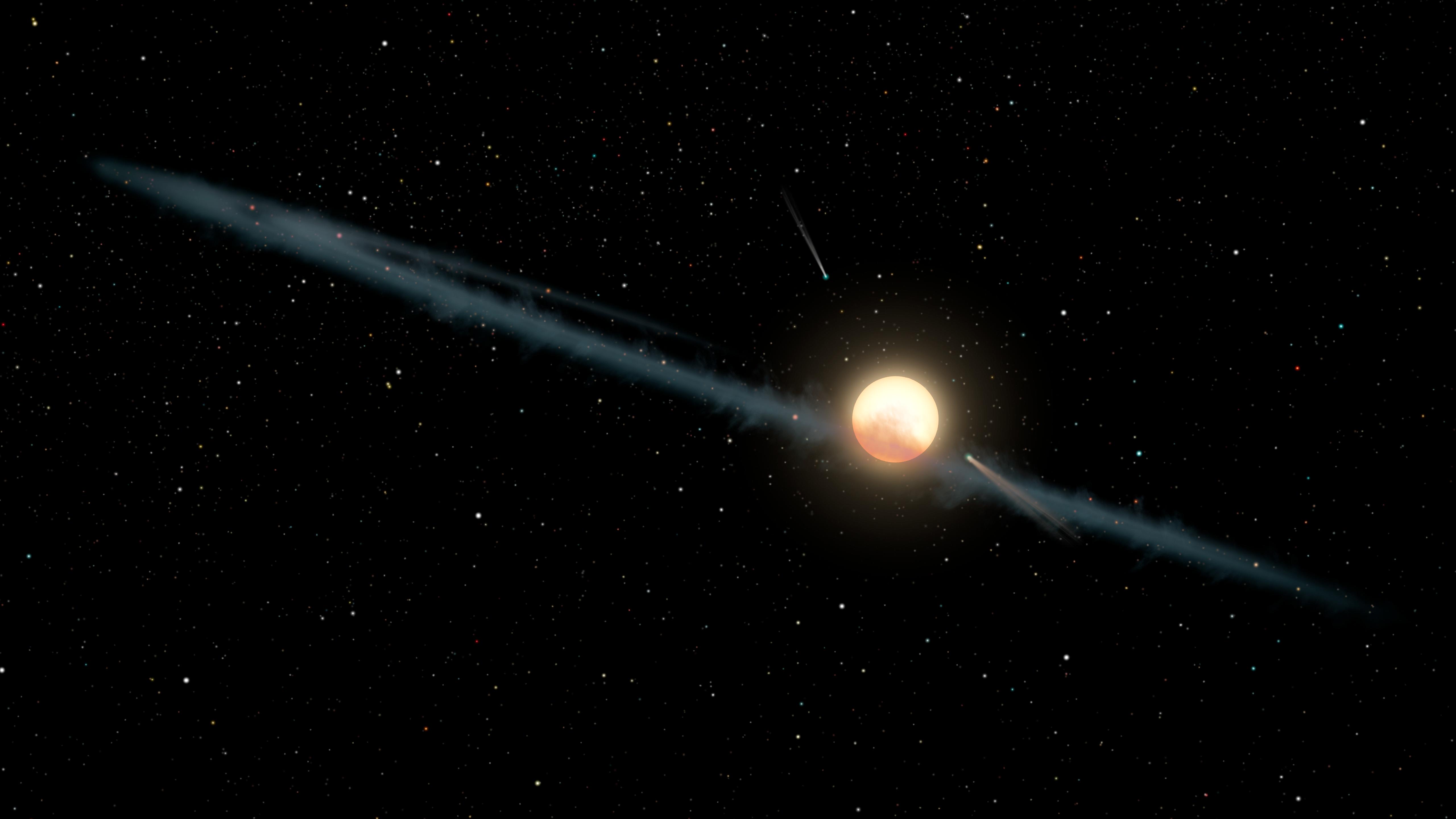

Concepts like NASA’s Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO) and the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT), and Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) aim to suppress starlight and directly image Earth-sized planets, enabling detailed spectra of potentially habitable worlds.

“For the first time, we have a realistic path to measuring the atmospheres of temperate, Earth-sized exoplanets—and that means we can start treating the search for life as an experimental science.” — adapted from commentary by exoplanet researchers in Nature.

While JWST excels at detailed characterization of larger and hotter exoplanets today, its most transformative contribution may be methodological: developing the observing strategies, calibration pipelines, and atmospheric retrieval tools that next‑generation telescopes will rely on to interrogate truly Earth-like worlds.

Technology: From Photons to Atmospheric Fingerprints

Turning faint, noisy data into a physically meaningful atmosphere requires a chain of advanced technology and theory, from detectors and coronagraphs to high‑performance retrieval codes.

Transmission Spectroscopy and Retrieval Methods

In transmission spectroscopy, JWST records the drop in stellar brightness as a function of wavelength during a transit. The depth of the transit varies slightly with wavelength depending on which molecules absorb in the atmosphere. Scientists then use retrieval algorithms—Bayesian inference frameworks that compare models to data—to estimate:

- Atmospheric composition (e.g., H2O, CO2, CH4, CO, SO2, possible hazes).

- Temperature–pressure profiles.

- Cloud and haze properties.

- Bulk planetary properties (scale height, mean molecular weight).

Different retrieval codes (e.g., CHIMERA, ATMO, TauREx, NEMESIS) can yield slightly different results, especially for marginal detections. This is why expert threads on Twitter/X and detailed YouTube breakdowns focus so heavily on assumptions: priors, cloud parameterizations, stellar contamination, and correlated noise.

High‑Contrast Imaging and Coronagraphy

Direct imaging of Earth analogues requires suppressing starlight by factors of 109–1010, comparable to spotting a firefly next to a lighthouse from thousands of kilometers away. Future missions such as HWO plan to combine:

- Advanced coronagraphs that block starlight within the telescope.

- Possibly an external starshade in some mission concepts.

- Extreme adaptive optics on ground‑based giants (ELT, GMT, TMT).

Recommended Reading and Tools for Enthusiasts

Interested readers can follow missions and technology via NASA’s exoplanet portal and ESA’s exoplanet pages, as well as technical talks on the NASA Exoplanets YouTube channel. For a deeper technical dive, the open-access white paper on the Habitable Worlds Observatory (arXiv) outlines planned instrumentation and science goals.

Scientific Significance: What Counts as a Biosignature?

A biosignature is any measurable feature—usually in a planet’s atmosphere or surface spectrum—that requires or strongly suggests the presence of life. However, no single molecule is “smoking‑gun” evidence. Context is everything.

Classic Atmospheric Biosignatures

- Oxygen (O2) and Ozone (O3) in high abundance, especially with:

- Methane (CH4) at levels that cannot be maintained by known abiotic processes.

- Strong redox disequilibrium, such as coexistence of oxidizing and reducing gases well out of thermochemical equilibrium.

- Organosulfur compounds (e.g., dimethyl sulfide, DMS) in specific contexts.

- Nitrogen species that hint at biological cycling.

“Life is more likely to reveal itself through patterns of gases and energy flows than through any single miraculous molecule.” — paraphrasing insights from astrobiologist Sara Seager and colleagues.

Contextual Biosignatures

Modern thinking emphasizes contextual biosignatures—combinations of observations interpreted within detailed planetary models:

- Stellar context: UV flux, flares, and spectral type of the host star.

- Planetary context: mass, radius, irradiation, expected volcanic/outgassing rates.

- Geochemical models: equilibrium chemistry of rocks, oceans, and atmospheres.

- Temporal variability: seasonal or secular changes that might reflect biological cycles.

This holistic view is formalized in frameworks such as the Astrobiology Science Strategy from the U.S. National Academies and in recent NASA biosignature standards papers.

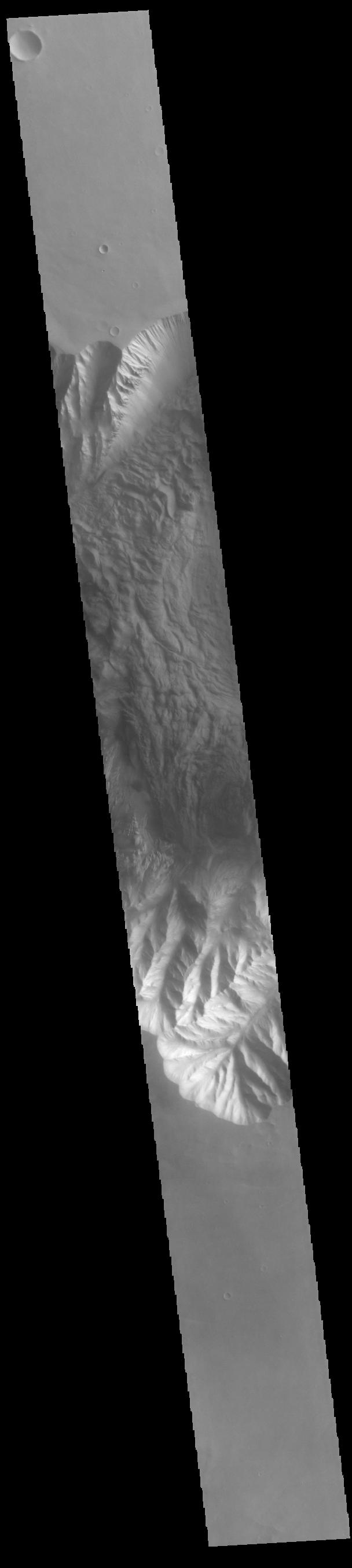

Mission Targets: Candidate Habitable Worlds and JWST’s Early Results

JWST’s first exoplanet results have focused on a mix of hot gas giants, warm mini‑Neptunes, and a few rocky planets around nearby M‑dwarf stars. While no confirmed biosignature has been detected, these observations are stress‑testing models and informing future strategies.

M‑Dwarf Systems and the TRAPPIST‑1 Planets

Compact systems around cool red dwarfs—especially TRAPPIST‑1—remain top priorities because their small stars make the transit signals of Earth-sized planets relatively large. However, strong stellar activity and potential atmospheric erosion create major uncertainties.

- Early JWST observations suggest no thick, hydrogen‑rich atmospheres for some TRAPPIST‑1 planets.

- Whether they retain thinner secondary atmospheres (e.g., N2, CO2) remains under investigation.

- Long-term monitoring is required to constrain atmosphere loss from flares and stellar winds.

Ambiguous Chemical Hints

From hot Jupiters to temperate sub‑Neptunes, JWST has reported tentative signs of:

- Water vapor (H2O) in multiple atmospheres.

- Carbon dioxide (CO2) with high signal‑to‑noise on some worlds.

- Methane (CH4), carbon monoxide (CO), and sulfur dioxide (SO2) in specific hot planets.

In at least one widely publicized case, spectra were initially speculated to hint at more exotic molecules like dimethyl sulfide (DMS), a molecule associated with marine biology on Earth. Rapid follow‑up analyses highlighted:

- The low statistical significance of the spectral feature.

- Degeneracies with clouds, hazes, and other molecules.

- Systematic uncertainties in instrument calibration and stellar contamination.

This pattern—early excitement, followed by careful reanalysis—is a healthy hallmark of a maturing field rather than evidence of failure. It underscores the need for multiple lines of evidence before any biosignature claim.

Future Missions: Habitable Worlds Observatory and Giant Telescopes

While JWST is revolutionizing exoplanet science today, it will not be the final word on life detection. Several next‑generation facilities are being designed specifically with habitable planets in mind.

Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO)

HWO is a NASA mission concept, recommended as a top priority by the Astro2020 Decadal Survey, that aims to directly image and spectroscopically characterize dozens of Earth‑size planets in the habitable zones of Sun‑like stars.

Key goals include:

- Measuring atmospheric composition (O2, O3, CO2, CH4, H2O) for potentially habitable planets.

- Detecting surface–atmosphere interactions, such as oceans and continents.

- Searching for biosignature combinations in a statistical sample of Earth analogues.

Ground‑Based Giants: ELT, GMT, and TMT

Thirty‑ to forty‑meter‑class telescopes on the ground will complement space missions with higher spectral resolution and flexible instrumentation. They will:

- Probe atmospheric escape and composition at high resolution using techniques like high‑dispersion spectroscopy.

- Characterize non‑transiting planets via direct imaging in the infrared.

- Study stellar activity and magnetic environments that influence habitability.

Several white papers, including the ELT and GMT exoplanet roadmaps (arXiv:1903.07536), detail the synergy between space‑ and ground‑based assets for biosignature science.

Defining Life and Biosignatures: Beyond One‑Molecule Hype

One of the most vibrant discussions triggered by JWST data takes place not just in journals, but on social media and philosophy of science forums: what would actually convince us that an exoplanet hosts life?

From Single Molecules to Systems Thinking

Historically, enthusiasm focused on one or two molecules (e.g., O2, CH4). Modern astrobiology instead emphasizes:

- Systems-level disequilibrium: complex gas mixtures that are hard to explain abiotically.

- Planetary energy budgets: how incoming stellar flux is partitioned between reflection, reradiation, and chemical work.

- Temporal dynamics: seasonal or multi‑year variations suggestive of biological cycles.

“Life reshapes its planet’s atmosphere and surface over geologic time. The biosignature is not a single spectral line, but a long-term imbalance maintained against entropy.” — paraphrasing David Catling and colleagues.

Philosophical and Practical Criteria

Proposed criteria for a convincing biosignature detection often include:

- Robust detection: strong statistical significance across multiple instruments and epochs.

- Model completeness: careful exploration of all known abiotic pathways.

- Cross‑validation: independent teams, codes, and datasets reaching similar conclusions.

- Contextual consistency: atmospheric, geologic, and stellar context all support a biological interpretation.

Many experts argue that, as with the discovery of cosmic acceleration or gravitational waves, consensus will emerge gradually as multiple lines of evidence converge.

Online Discourse: How JWST Biosignatures Play Out on Social Media

Each major JWST exoplanet release now comes with a predictable pattern of online reaction, shaped by YouTube explainers, Twitter/X threads from astronomers, and short‑form TikTok content.

YouTube and Long‑Form Explainers

Science communicators and astrophysicists run channels that carefully walk through:

- How transit and eclipse spectroscopy work.

- What the reported spectra and error bars actually mean.

- Why retrieval models can give different answers.

Channels like NASA’s official YouTube and independent educators often host breakdowns of major exoplanet papers soon after publication.

Twitter/X Threads and Technical Debates

Professional astronomers frequently use Twitter/X to:

- Share annotated plots and re‑fits of spectra.

- Discuss retrieval choices, priors, and sensitivity tests.

- Flag caveats such as stellar spots or instrument systematics.

This rapid, open peer‑discussion can look like disagreement to outsiders, but it is a core part of how modern teams stress‑test claims before they enter textbooks.

TikTok, Instagram Reels, and Public Perception

Short‑form videos typically compress nuanced results into quick headlines, sometimes overstating certainty. Responsible communicators now try to:

- Frame claims as “possible hints” rather than “proof of aliens.”

- Highlight the role of follow‑up observations.

- Link to original papers or NASA/ESA press releases for context.

Tools and Resources for Following the Search

Enthusiasts who want to engage more deeply with exoplanet biosignature science can build a small toolkit of educational resources and instruments.

Books and Educational Resources

- Planet Hunters: The Search for Other Worlds — an accessible overview of how exoplanets are discovered and studied.

- Exoplanets — a more technical guide for advanced amateurs and students.

Amateur Observing and Data Engagement

While JWST-class data are out of reach for backyard telescopes, amateurs can still observe bright transiting exoplanets and contribute to light curve databases. Many use:

- Moderate‑aperture telescopes with sensitive CMOS or CCD cameras.

- Open‑source photometry software to produce transit light curves.

- Citizen‑science platforms like Exoplanet Explorers.

Learning to interpret light curves and basic spectra makes it much easier to understand JWST press releases and research papers.

Challenges: False Positives, False Negatives, and the Limits of JWST

Detecting life remotely is extraordinarily difficult. Several categories of challenge are especially important when interpreting prospective biosignatures.

False Positives

False positives occur when abiotic processes mimic biosignature patterns. Examples include:

- Photochemical production of O2 and O3 on dry planets with strong UV irradiation.

- Volcanic outgassing producing methane or other reduced gases.

- Surface mineral reactions that generate disequilibrium gas mixtures.

Detailed photochemical and geochemical models are required to rule out such scenarios for each candidate planet.

False Negatives

False negatives arise when life is present but leaves weak or ambiguous atmospheric traces:

- Subsurface or ocean worlds where biology is shielded from the atmosphere.

- Worlds early in their biospheric evolution, before large‑scale oxygenation.

- Planets where geological and biological fluxes cancel out obvious imbalances.

Our Earth itself would not always have looked obviously inhabited to a distant observer—particularly before the Great Oxidation Event.

Instrumental and Modeling Limitations

- Finite collecting area limits the signal‑to‑noise ratio for small, distant planets.

- Instrument systematics and stellar variability complicate the interpretation of subtle signals.

- Model degeneracies—different atmospheric compositions producing similar spectra—can hinder firm conclusions.

These limitations motivate long campaigns on a small number of high‑value targets and a strong emphasis on cross‑validation across instruments and observatories.

Milestones: What to Watch for in the Coming Decade

Between now and the launch of HWO and the full operation of ELT‑class telescopes, several milestones will shape the search for exoplanet biosignatures.

Near‑Term (Next 3–5 Years)

- Completion of JWST observing programs on key rocky planets around nearby M‑dwarfs.

- Refined atmospheric constraints (or upper limits) for TRAPPIST‑1 and similar systems.

- Improved retrieval frameworks with better cloud, haze, and stellar contamination modeling.

Medium‑Term (5–10+ Years)

- First-light science from ELT, GMT, and TMT with exoplanet-focused instruments.

- Selection and design maturation of HWO, including coronagraph capabilities.

- Development of community standards for biosignature claims and verification protocols.

The overarching goal is to move from one‑off case studies to a population‑level view of habitable and inhabited worlds.

Conclusion: A Careful, Data‑Driven Path to Answering “Are We Alone?”

JWST has inaugurated a new era in which the search for life beyond Earth is increasingly empirical. By dissecting exoplanet atmospheres and developing robust frameworks for biosignature interpretation, scientists are laying the groundwork for future observatories that may finally identify inhabited worlds.

The path forward will almost certainly involve:

- Long‑term monitoring of a small set of nearby temperate planets.

- Synergy between JWST, ground‑based giants, and future space missions like HWO.

- Interdisciplinary collaboration among astronomers, chemists, geologists, biologists, and philosophers of science.

Whether the first compelling biosignature is discovered next decade or much later, the process itself—refining our tools, concepts, and expectations—will profoundly deepen our understanding of planets, life, and our place in the universe.

Additional Insights: How to Critically Read Exoplanet “Life” Headlines

Because biosignature stories travel quickly online, it helps to have a simple checklist for evaluating new claims you encounter in news articles or social media posts.

Five Questions to Ask

- What is actually detected?

Is it a specific molecule, a combination of gases, or just a tentative spectral feature? - How strong is the signal?

Look for mentions of detection significance (e.g., 3σ, 5σ) and whether multiple instruments or visits confirm it. - Are abiotic explanations discussed?

Robust papers spend significant space exploring non‑biological pathways. - Is the context clear?

Do authors provide stellar, planetary, and geochemical context, not just atmospheric composition? - What do independent experts say?

Check for commentary from researchers not involved in the original study, often on Twitter/X, blogs, or review articles.

Applying this filter helps distinguish between speculative excitement and genuinely transformative discoveries as the exoplanet biosignature field continues to evolve.

References / Sources

- NASA Exoplanet Exploration Program

- JWST Science: Exoplanets

- ESA Exoplanet Science

- Catling, D.C., Krissansen-Totton, J., et al., “Exoplanet Biosignatures: A Framework for Their Assessment” (arXiv:1802.01531)

- Schwieterman, E.W. et al., “A Review of Possible Exoplanet Biosignatures” (PNAS)

- National Academies, “Astrobiology Science Strategy for the Search for Life in the Universe”

- Habitable Worlds Observatory Mission Concept (arXiv:2303.02168)

- NASA feature: Exoplanet Biosignatures