Measles Outbreak in Snohomish County: What Parents Need to Know Right Now

Measles Cases Spread in Snohomish County: A Practical Guide for Concerned Parents

A recent measles outbreak in Snohomish County has now spread to more unvaccinated children after an exposure linked to a visiting family from South Carolina, according to The Seattle Times and local public health officials. If you’re a parent or caregiver in Washington state—or anywhere measles can travel by plane or car—this kind of news can feel frightening and confusing.

This article walks you through what is known so far about the Snohomish County measles cases, how measles spreads, when to worry, and what you can do today to lower your family’s risk. You’ll find evidence-based guidance, practical checklists, and reassurance grounded in what doctors and public health agencies recommend, not in hype or fear.

What’s Happening in Snohomish County Right Now?

According to recent reporting by The Seattle Times, the Snohomish County Health Department confirmed that:

- Three children were initially infected with measles earlier this month after contact with a contagious visiting family from South Carolina.

- Public health officials have since confirmed three additional measles cases in children, bringing the total to at least six linked cases.

- The affected children are reported to be unvaccinated or not fully vaccinated against measles.

Health officials are working to:

- Identify locations where contagious individuals may have exposed others (such as clinics, stores, or community events).

- Notify people who may have been in those places at the same time.

- Encourage families to review vaccination records and contact healthcare providers if exposure is suspected.

“Measles is so contagious that if one person has it, up to 90% of the people close to that person who are not immune will also become infected.”

— U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

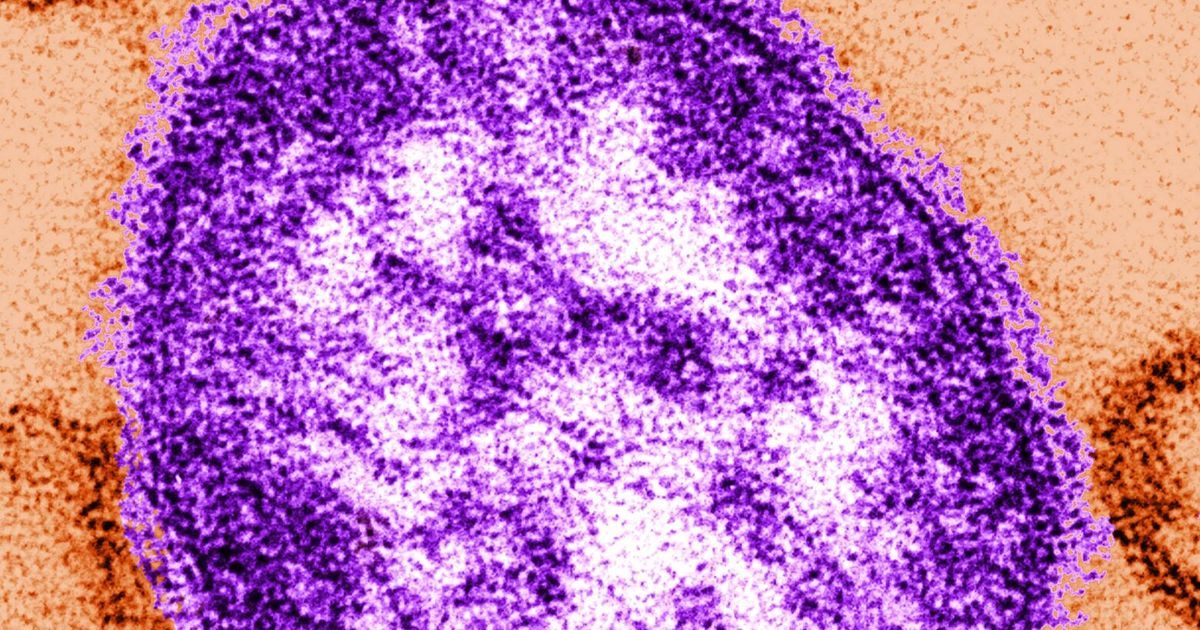

Measles 101: Symptoms, Risks, and How It Spreads

Measles is a viral infection that spreads through the air when an infected person coughs or sneezes. The virus can linger in the air and on surfaces for up to two hours, which is why it spreads so efficiently in homes, schools, and clinics.

Common measles symptoms

- High fever, often 101°F (38.3°C) or higher

- Cough, runny nose, and red, watery eyes

- Tiny white spots inside the mouth (called Koplik spots)

- Reddish rash that usually starts on the face and spreads down the body

Symptoms typically appear about 7–14 days after exposure. People are contagious from roughly 4 days before the rash appears to 4 days after.

Who is at highest risk of complications?

While anyone who is not immune can catch measles, complications tend to be more serious for:

- Children under 5 years old

- Adults over 20

- Pregnant people

- People with weakened immune systems (e.g., cancer treatment, certain medications, advanced HIV)

Complications can include ear infections, pneumonia, swelling of the brain (encephalitis), and in rare cases, death. The CDC and World Health Organization (WHO) both emphasize that vaccination drastically reduces these risks.

Think You Were Exposed? Step-by-Step What to Do

If you live in or recently visited Snohomish County (or another area with a reported measles case) and are worried about exposure, it helps to follow a clear, calm plan.

1. Check whether you were actually in an exposure location

Public health departments usually publish a list of “exposure sites” (for example, clinics, grocery stores, or airports) with dates and times when a contagious person was present. If you were in one of these locations around the same time, you may have been exposed.

2. Review your vaccination or immunity status

- Children: Check their immunization record for MMR (measles, mumps, rubella). Fully vaccinated usually means:

- First dose at 12–15 months, and

- Second dose at 4–6 years (or at least 28 days after the first, if given earlier).

- Adults: Many adults received the measles vaccine as children. If you are unsure, your healthcare provider can:

- Look up immunization records (if available), or

- Order a blood test to check for measles immunity.

3. Call your healthcare provider or local health department

If you may have been exposed and are unsure of your immunity—or if anyone in your home is at high risk (infants, pregnant people, immunocompromised)—contact your healthcare provider or local health department promptly for tailored advice. They may recommend:

- A “catch-up” MMR vaccine for people who are eligible but not fully vaccinated.

- In some high-risk cases, immune globulin (a type of passive immunity) within a specific time window after exposure.

- Home monitoring or temporary isolation, depending on symptoms and vaccination history.

“Our role isn’t to scare families—it’s to give them clear steps. If you think you were exposed, call us. We’d much rather answer questions early than see a child get severely ill.”

— Hypothetical comment from a county public health nurse, summarizing standard practice

The Measles Vaccine: What Evidence Actually Shows

In the Snohomish County outbreak, health officials have emphasized that the confirmed cases so far are in unvaccinated or under-vaccinated children. This pattern matches decades of research showing that communities with lower vaccination coverage are more vulnerable to outbreaks.

The measles vaccine is typically given as the MMR vaccine. Large studies and reviews, including those published in journals like The Lancet and supported by the CDC and WHO, show that:

- One dose of MMR is about 93% effective at preventing measles.

- Two doses are about 97% effective.

- Serious side effects are rare compared with the risks of measles illness itself.

Addressing common concerns (without judgment)

Many parents carry old worries about the MMR vaccine, especially myths linking it to autism. These claims have been repeatedly and thoroughly disproven in large, well-designed studies across multiple countries. The original paper that raised this concern was found to be fraudulent and was formally retracted.

It’s completely understandable to want to double-check anything involving your child’s health. A constructive next step is to bring your questions to a trusted pediatrician or family doctor who can walk through the latest evidence and your child’s specific situation.

A Real-World Example: One Family’s Measles Scare

A Seattle-area pediatrician recently shared (with details changed to protect privacy) the story of a family during a previous regional measles exposure:

A mother of two called the clinic in tears after learning that a measles case had visited the same grocery store she had taken her 10-month-old baby to a few days prior. Her baby was too young for the routine first MMR shot, and she worried she had made a terrible mistake by going out.

The clinic walked her through the timeline and consulted the local health department. Because the baby was within the time window for post-exposure protection, they arranged for immune globulin and set up close follow-up visits. The baby never developed measles.

This family’s experience underscores two important points:

- You are not alone if you feel anxious or guilty after hearing about an exposure.

- Early communication with your healthcare team opens up more options to protect your child.

Common Obstacles: Cost, Access, and Hesitation

Even when parents want to vaccinate or seek care promptly, real-world barriers can get in the way. Recognizing these challenges is the first step in overcoming them.

1. “We don’t have a regular doctor.”

If your family doesn’t have a primary care provider, start with:

- Community health centers or federally qualified health centers in your area.

- County health department clinics that often offer childhood vaccines.

- School-based health centers, where available.

2. Worry about cost

In the U.S., the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program helps ensure that recommended vaccines are available at no cost for eligible children, including those who are uninsured or underinsured. Many local health departments also offer low-cost or free childhood immunizations.

3. Feeling overwhelmed by conflicting information

Online information about measles and vaccines can be confusing. A practical approach is to:

- Pick two or three trusted sources (such as your local health department, CDC, and a pediatric organization).

- Write down your questions as they come up.

- Bring the list to your next appointment or telehealth visit.

Practical Prevention Plan for Your Household

While no plan can guarantee zero risk, there are concrete steps you can take to reduce your family’s chances of getting measles—during the Snohomish County outbreak and beyond.

Your 5-step home checklist

- Update vaccination records. Check each family member’s MMR status and schedule needed doses.

- Know your local resources. Save phone numbers for your pediatrician, after-hours nurse line, and local health department.

- Create a “sick plan.” Decide in advance where a sick child will rest, who can take time off work, and how you’ll manage childcare.

- Practice respiratory hygiene. Teach kids to cover coughs and sneezes, and to wash hands frequently—habits that help with many infections.

- Stay informed, not overwhelmed. Set a reasonable limit on news and social media scrolling; check updates from one or two official sources instead.

Moving Forward: Staying Calm, Prepared, and Connected

News about measles spreading among children—as in the current Snohomish County outbreak—can stir up worry, frustration, or even guilt. Those feelings are completely human. They also don’t have to be the end of the story.

By understanding how measles spreads, reviewing your family’s MMR vaccination status, and building a simple plan with your healthcare team, you can turn uncertainty into practical action. Public health is a shared effort; every family that gets informed and up to date on vaccines helps protect not only their own children but also neighbors, classmates, and those who can’t be vaccinated.

If you’re in or near Snohomish County, consider taking these next steps today:

- Visit the Snohomish County Health Department website for the latest exposure sites and guidance.

- Log in to your clinic portal or call your pediatrician to confirm your child’s MMR status.

- Share accurate, source-based information with a friend or family member who might also be worried.

You don’t have to navigate this alone. Reach out, ask questions, and take one doable step at a time—those small actions add up to powerful protection for your child and your community.