How to Stay Safe in Washington’s New Measles Outbreak (Without Panicking)

Washington state is facing its first measles outbreak in years, and if you live in or near Snohomish County—or simply have kids in school—this news probably lands like a punch in the gut. Measles is highly contagious, and hearing that health officials “firmly believe” there are more infections out there than they’ve found can feel deeply unsettling.

The good news: we know a lot about measles, the measles vaccine is highly effective, and there are clear, evidence-based steps you can take to lower your risk and help protect your community. This guide walks you through what’s happening in Washington, how measles spreads, what symptoms to watch for, and what to do—practically and calmly—over the next few weeks.

What’s Happening With the Measles Outbreak in Washington?

Local public health teams in at least two Washington counties—including Snohomish County—are racing to confirm vaccination records for students and families after the state identified its first measles outbreak in years. According to reports, the county’s health officer has said he “firmly believes” there are additional infections that haven’t yet been detected.

This doesn’t necessarily mean things are spiraling out of control—it means health officials understand how easily measles spreads and are acting early and aggressively to interrupt transmission. That includes:

- Verifying who is fully vaccinated (especially school-aged children).

- Notifying people who may have been exposed at specific locations and times.

- Recommending temporary exclusion from school or public settings for those who are not immune.

- Encouraging rapid vaccination for people who are unvaccinated or under-vaccinated.

“With measles, we have to assume there are more infections than we’ve already found. That’s not a reason to panic—it’s a reason to double-check immunity and move fast on vaccination.”

— Local health officer, Snohomish County (as reported by The Seattle Times)

Measles 101: Why This Virus Gets Public Health’s Full Attention

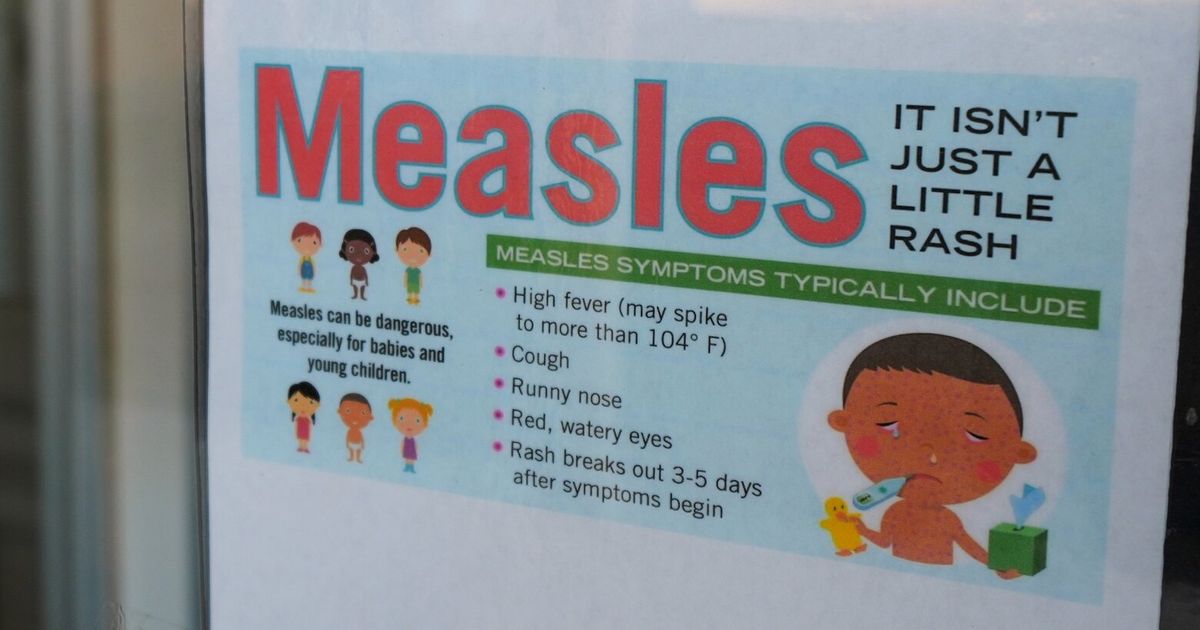

Measles isn’t “just a rash.” It’s a serious viral illness that can lead to pneumonia, brain inflammation (encephalitis), hospitalization, and—rarely—death, especially in young children and people with weakened immune systems.

How measles spreads

Measles is one of the most contagious diseases known. The virus spreads through:

- Tiny droplets in the air when an infected person coughs or sneezes.

- Lingering particles that can stay in the air for up to two hours after a sick person leaves a room.

- Touching surfaces with the virus and then touching your mouth, nose, or eyes.

If you’re not immune, your chance of getting sick after being exposed is extremely high—around 9 out of 10.

Common measles symptoms

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), measles usually progresses in stages:

- Early symptoms (days 1–4): High fever, cough, runny nose, red or watery eyes.

- Koplik spots: Tiny white spots inside the mouth (not always noticed by families).

- Rash: Starts on the face at the hairline and spreads downward to the chest, back, arms, legs, and feet.

People with measles can spread the virus from about 4 days before the rash appears until 4 days after it shows up.

How Well Does the Measles (MMR) Vaccine Protect You?

The measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine is the single most important tool we have to prevent measles outbreaks. Large studies over several decades show:

- One dose of MMR is about 93% effective at preventing measles.

- Two doses are about 97% effective, which is why two doses are routinely recommended.

That means breakthrough cases can happen, but they’re uncommon—and vaccinated people who do get measles usually have milder illness and are less likely to develop complications.

Who is considered “immune” to measles?

In general, public health officials consider you protected if:

- You have written documentation of two doses of MMR given after age 1, OR

- You have a lab test showing measles immunity, OR

- You were born before 1957 (and likely had natural infection as a child), unless you work in healthcare, where additional proof may be required.

If you’re unsure, your doctor can help interpret old records, order a blood test for immunity if appropriate, or recommend catch-up vaccination.

“In every modern measles outbreak we’ve studied, the vast majority of cases occur in unvaccinated or under-vaccinated groups. Closing those gaps is how we stop outbreaks.”

— Infectious disease epidemiologist, referencing CDC outbreak data

Practical Steps to Protect Your Family During the Washington Measles Outbreak

Feeling worried is understandable. The key is to channel that concern into specific, manageable actions. Here’s a step-by-step approach you can take over the next few days.

1. Confirm your family’s MMR vaccination status

- Check your records. Look for your child’s immunization card, school vaccine forms, or your state’s online immunization registry (in Washington, this is often accessed through your clinic or state health portal).

- Call your clinic if you’re unsure. Ask specifically how many MMR doses are documented and on what dates.

- Schedule catch-up shots if needed. The CDC provides guidance on accelerated schedules during outbreaks; clinics in affected counties may have special hours or walk-in options.

2. Pay close attention to public health alerts

Counties usually post exposure locations (like specific schools, clinics, or businesses) and time windows where people may have been exposed. To stay updated:

- Bookmark your local health department website (e.g., Snohomish Health District, Washington State Department of Health).

- Sign up for text or email alerts if available.

- Follow official accounts on social media rather than relying on unverified posts.

3. Know what to do if you think you were exposed

If you were at a listed exposure site during the specified time:

- If you’re fully vaccinated: Your risk is low. Monitor for symptoms for 21 days and follow local guidance.

- If you’re not vaccinated or unsure: Call your doctor or local health department promptly. In some cases, getting the MMR vaccine within 72 hours of exposure can reduce your chance of getting sick.

- If you’re high-risk (pregnant, immunocompromised, or have an infant too young for MMR): ask specifically about additional protective measures such as immune globulin, which may be recommended in some situations.

4. Make temporary adjustments, not permanent fear-based changes

You may choose to temporarily avoid crowded indoor places with lots of young children if:

- You have a baby too young for MMR, or

- Someone in your household is immunocompromised and not fully protected.

This doesn’t mean locking down indefinitely—it’s about making informed, short-term adjustments while public health teams do their work.

Real-Life Obstacles: What Gets in the Way—and How to Work Around It

In theory, everyone just “checks their records and gets vaccinated.” In real life, it’s messier. Lost paperwork, busy schedules, and lingering worries or confusion about vaccines are all common.

“I can’t find my or my child’s vaccine records.”

- Start with your child’s pediatrician or your primary care clinic; many records are stored electronically.

- Contact previous clinics or schools if you’ve moved.

- Ask your state health department about access to the state immunization registry.

- If records truly can’t be found, most experts recommend vaccinating again rather than risking being unprotected; extra doses are generally safe for healthy people.

“I’m worried about vaccine side effects.”

It’s reasonable to have questions, especially if it’s been years since you thought about childhood vaccines. What research consistently shows:

- The most common side effects of MMR are mild: soreness at the injection site, low-grade fever, or mild rash.

- Serious side effects are rare and are monitored continuously by systems like VAERS and the Vaccine Safety Datalink.

- Large, well-designed studies have not found a link between MMR vaccination and autism.

“When I counsel parents during an outbreak, I’m honest about mild side effects—but I also walk them through what measles itself can do. The risks of the disease are far higher than the risks of the vaccine for most people.”

— Pediatrician, community health clinic

Case example: A Snohomish family’s weekend plan

A family with a 4-year-old in preschool and a 6-month-old baby called their clinic after hearing about the outbreak. The older child had one MMR dose; the baby was still too young for the vaccine. After reviewing the situation, the pediatrician:

- Scheduled the 4-year-old for a second MMR dose as soon as possible.

- Reviewed exposure locations with the parents and reassured them that their preschool wasn’t on the list.

- Suggested they avoid very crowded indoor play areas with the baby for a couple of weeks, but said school and outdoor activities were reasonable to continue.

This kind of tailored, practical plan—rather than all-or-nothing restrictions—can significantly reduce risk while preserving as much normal life as possible.

Visual Guide: Measles Risk and Protection at a Glance

The chart below summarizes how vaccination status and recent exposure influence your measles risk and next steps. This isn’t a substitute for medical advice, but it can help you frame your conversation with a healthcare professional.

| Situation | Relative Risk | Typical Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Two documented MMR doses, no known exposure | Low | Monitor public health updates; no extra steps beyond routine care. |

| Two MMR doses, known exposure at listed site | Still low | Watch for symptoms for 21 days, follow any local instructions. |

| Unvaccinated or one dose, known exposure | Higher | Call provider or health department promptly; discuss rapid MMR or immune globulin if eligible. |

| Infant too young for MMR, in affected area | High if exposed | Minimize high-risk settings; consult pediatrician if exposures occur. |

Managing Anxiety: Staying Informed Without Feeling Overwhelmed

Health news—especially about contagious diseases—can stir up old fears from the pandemic years. It’s completely human to feel a spike of anxiety when you see the word “outbreak.”

- Limit doom-scrolling. Choose 1–2 trusted sources (like your county health department and the CDC) and check them once or twice a day instead of refreshing constantly.

- Focus on your “next right step.” That might be calling your pediatrician, checking your own records, or simply writing down questions for tomorrow.

- Talk with your kids calmly. Simple, reassuring language like, “Doctors and nurses are working to keep everyone safe, and we’re doing our part by checking our shots,” helps them feel secure.

- Lean on your community. Coordinate with other parents for information sharing and support, but always verify details through official channels.

Moving Forward: Calm, Informed Action Is Your Best Protection

Washington’s measles outbreak is serious, but it’s not a reason to panic. It’s a call to do what we know works: verify immunity, close vaccination gaps, stay alert to symptoms, and support public health teams who are working to find and contain every case.

If you’re in or near the affected counties, your most impactful steps over the next few days are:

- Check your and your family’s MMR vaccination records.

- Reach out to your clinic if anything is missing or unclear.

- Follow local health department alerts about exposure sites and guidance.

- Have a calm, honest conversation with your household about what you’re doing to stay safe.

Outbreaks are stressful, but they’re also temporary. With high vaccination coverage and communities that look out for one another, measles can be pushed back into the rare, headline-making event it’s become—and kept from becoming a regular part of our lives again.

If you have questions about your risk or your child’s vaccines, your next best step is to contact your healthcare provider or local health department today—they’re ready for these questions, and you don’t have to navigate this alone.