How James Webb Is Rewriting the Story of the Early Universe

The James Webb Space Telescope is the most powerful space observatory ever launched, designed as the scientific successor to the Hubble Space Telescope. Stationed at the Sun–Earth L2 Lagrange point, JWST operates primarily in the near- and mid‑infrared, allowing it to peer through interstellar dust and see light stretched by the universe’s expansion from the first generations of stars and galaxies.

Since beginning science operations in mid‑2022, JWST has transformed research in cosmology, galaxy evolution, exoplanets, and stellar astrophysics. Its early-release images—such as the Carina Nebula, Stephan’s Quintet, and the Cosmic Cliffs—set the stage, but the most profound revolution has come from its deep surveys and high‑precision spectroscopy.

Mission Overview

JWST is a joint mission of NASA, ESA (European Space Agency), and CSA (Canadian Space Agency). Its primary mirror is a segmented 6.5‑meter beryllium reflector coated in gold, giving it more than six times Hubble’s light‑collecting area. A multi‑layer sunshield the size of a tennis court keeps the telescope extremely cold—below 50 K—so that its own thermal emission does not drown out the faint infrared signals from the distant universe.

- Launch date: 25 December 2021 (Ariane 5 from Kourou, French Guiana)

- Operational orbit: Around the Sun–Earth L2 point, ~1.5 million km from Earth

- Primary wavelength coverage: ~0.6–28 micrometers (near‑IR to mid‑IR)

- Key science themes: First light and reionization, galaxy assembly, star and planet formation, exoplanet systems and their atmospheres

“Webb is designed to answer questions we didn’t even know how to ask when Hubble launched.” — John Mather, Nobel laureate and JWST senior project scientist

Technology: How JWST Sees the Invisible Universe

JWST’s discoveries are driven by a carefully integrated suite of instruments and engineering innovations. Unlike Hubble, which operates mainly in optical and ultraviolet light, JWST is optimized for infrared astronomy, where the glow of the early universe and cool objects like exoplanets is brightest.

Key Instruments

- NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera): JWST’s primary imager for 0.6–5 μm, used for deep galaxy surveys and mapping star‑forming regions.

- NIRSpec (Near-Infrared Spectrograph): Capable of obtaining spectra of up to hundreds of objects at once using a micro‑shutter array—crucial for high‑redshift galaxy surveys.

- MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument): Extends sensitivity to 28 μm, revealing cold dust, molecular gas, and protostellar disks.

- FGS/NIRISS (Fine Guidance Sensor / Near‑Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph): Provides precision pointing and specialized modes for exoplanet transit spectroscopy and high‑contrast imaging.

Why Infrared Matters

Due to cosmic expansion, light from the earliest galaxies is redshifted from ultraviolet and visible wavelengths into the infrared by the time it reaches us. Dust in star‑forming regions also absorbs and scatters visible light but lets longer‑wavelength infrared pass through. JWST’s infrared sensitivity therefore:

- Reaches back to the “Cosmic Dawn,” when the first stars and galaxies formed.

- Penetrates dusty birth clouds to study the physics of star and planet formation.

- Measures thermal emission and molecular absorption in exoplanet atmospheres.

Mission Overview: Peering Into the Early Universe

One of JWST’s headline goals is to identify and characterize the earliest galaxies, formed within the first few hundred million years after the Big Bang. By late 2025, JWST programs such as CEERS, JADES, GLASS, and UNCOVER had uncovered populations of candidate galaxies with redshifts z > 10 and even tentative systems approaching z ≈ 14–16, corresponding to just ~250–300 million years after the Big Bang.

High‑Redshift Galaxy Surveys

Early imaging suggested that some of these galaxies were surprisingly bright and massive given their early cosmic age. This generated intense discussion: were galaxies forming stars more efficiently than models assumed, or were researchers mis‑estimating distances and masses due to selection biases and uncertainties in photometric redshifts?

- Photometric redshifts from broad‑band colors first flagged high‑z candidates.

- Spectroscopic redshifts with NIRSpec later confirmed many of the most distant objects.

- Some initially extreme claims were revised downward, but a consistent picture emerged: galaxy assembly at early times was faster and more efficient than many pre‑JWST models predicted.

“No matter how we slice the data, Webb is telling us that galaxies were forming stars vigorously much earlier than expected.” — Brant Robertson, astrophysicist, UC Santa Cruz

Scientific Significance: Reionization and the First Generations of Light

The era of cosmic reionization marks the transition from a neutral hydrogen‑filled universe to one where the intergalactic medium became ionized by the first luminous sources. Understanding when and how this process unfolded is central to modern cosmology.

Constraining the Timeline of Reionization

JWST measures the Lyman‑α line and rest‑frame ultraviolet continuum from large samples of early galaxies. Combining this with data from the Planck satellite and ground‑based surveys, astronomers are:

- Mapping how the fraction of ionized hydrogen evolves with redshift.

- Testing whether galaxies alone can provide enough ionizing photons, or whether additional sources—Population III stars, mini‑quasars—are required.

- Studying the patchiness of reionization through line‑of‑sight variations and cross‑correlations with 21‑cm experiments such as HERA and LOFAR.

Dark Matter and Large‑Scale Structure

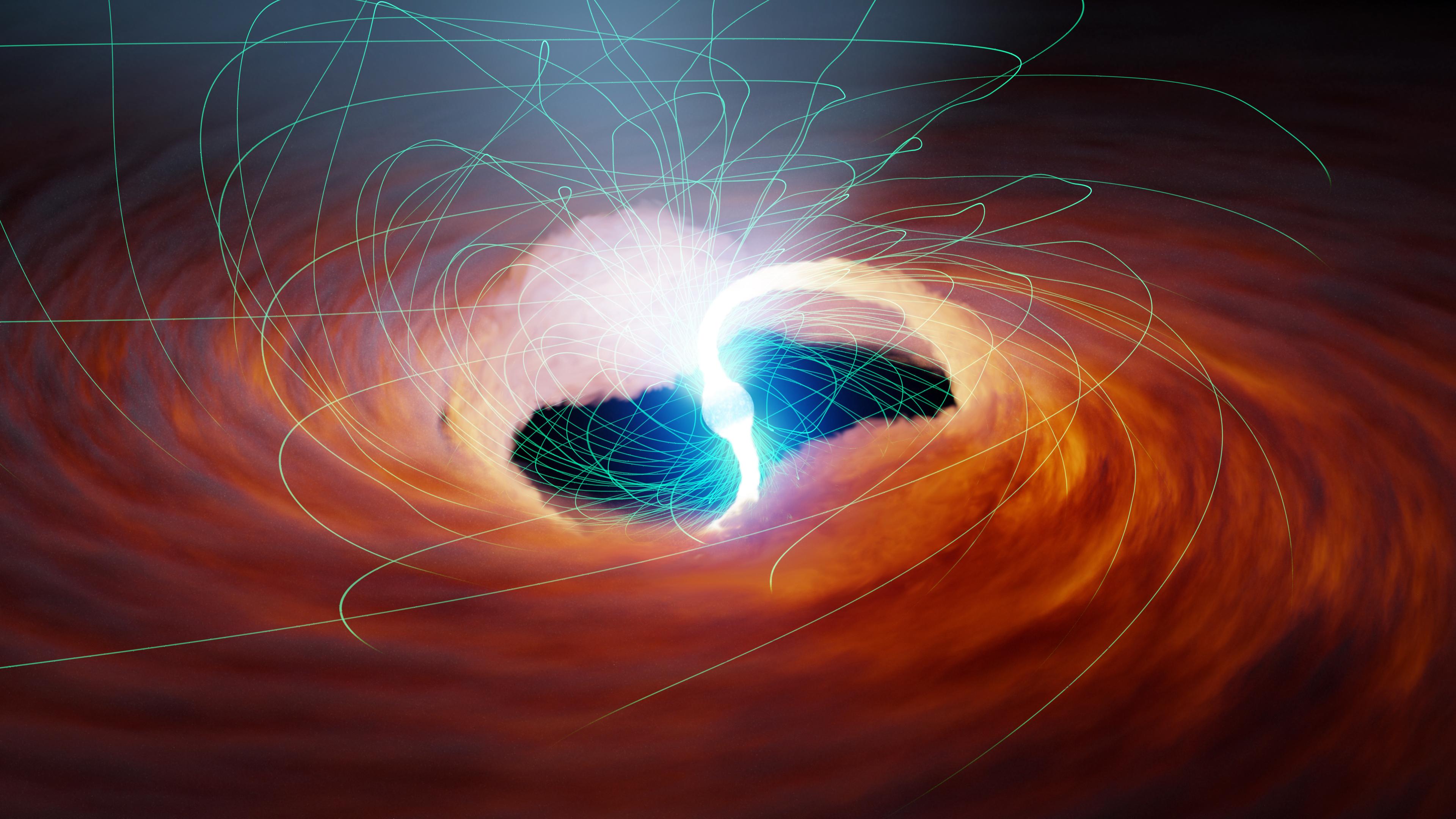

JWST also images galaxy clusters whose gravity creates strong gravitational lensing. These lenses both magnify background galaxies and provide a laboratory for testing dark‑matter distributions predicted by simulations.

- Detailed lensing maps reveal substructure in cluster mass distributions.

- Lensed high‑z galaxies—sometimes multiply imaged—allow astronomers to study extremely faint systems that would otherwise be below detection thresholds.

- Comparisons with ΛCDM (Lambda‑Cold Dark Matter) simulations test whether small‑scale structure behaves as expected or hints at more exotic dark‑matter physics.

Technology & Data: Galaxies, Cosmic Web, and Star‑Forming Regions

Beyond the earliest galaxies, JWST provides high‑resolution imaging and spectroscopy of more mature structures: spiral galaxies, interacting systems, and star‑forming regions within our own Milky Way and nearby galaxies.

Resolving the Morphology of Distant Galaxies

With NIRCam’s sharp infrared imaging, JWST resolves clumpy star‑forming knots, bulges, disks, and tidal features in galaxies across cosmic time. These data help answer core questions:

- When did stable disk galaxies like the Milky Way emerge?

- How important were mergers versus smooth gas accretion in building stellar mass?

- How does feedback from supernovae and active galactic nuclei regulate star formation?

Star‑Forming Nurseries and Protoplanetary Disks

JWST’s images of regions such as the Carina Nebula and the Orion Bar reveal:

- Jets and outflows from young stellar objects, carving cavities in molecular clouds.

- Protoplanetary disks with gaps and rings, suggestive of planet formation in progress.

- Complex organic molecules—such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)—illuminated by strong ultraviolet fields.

Technology: Exoplanet Atmospheres and the Search for Habitable Worlds

JWST is now the premier facility for characterizing exoplanet atmospheres. By observing transits and eclipses, it measures how starlight is absorbed, emitted, and scattered by alien worlds, revealing their composition, temperature structure, and cloud properties.

Transit and Eclipse Spectroscopy

During a transit, some starlight filters through the thin annulus of an exoplanet’s atmosphere. Different molecules absorb light at characteristic wavelengths, imprinting spectral signatures that JWST can detect.

- Transmission spectroscopy: Measures wavelength‑dependent transit depth to infer atmospheric composition.

- Emission spectroscopy: Observes secondary eclipses (when the planet passes behind the star) to isolate the planet’s thermal emission.

- Phase curves: Tracks brightness over an orbit to map temperature differences between day and night sides.

Highlight Discoveries (through early 2026)

- WASP‑39b: A hot Saturn‑mass planet whose JWST spectrum revealed clear carbon dioxide (CO2) absorption, sulfur dioxide (SO2) produced by photochemistry, and constraints on metallicity—benchmarking atmospheric models.

- TRAPPIST‑1 system: Repeated JWST observations of several Earth‑sized planets around this ultra‑cool dwarf are placing stringent upper limits on thick hydrogen atmospheres and probing for secondary atmospheres shaped by stellar activity.

- K2‑18b: A sub‑Neptune in the habitable zone, where JWST detected CO2 and methane (CH4) signatures consistent with a potential “Hycean” (ocean‑covered) world model, though interpretations remain under active debate.

“We’re not just seeing dots of light anymore—we’re reading the chemical fingerprints of other worlds.” — Nikku Madhusudhan, exoplanet scientist, University of Cambridge

For readers interested in the underlying physics of spectroscopy and exoplanet atmospheres, a highly accessible reference is the book Exoplanets by Michael Summers and James Trefil, which covers detection methods and atmospheric characterization at a level suitable for motivated non‑specialists.

Scientific Significance: From Preprints to Social Media Trends

JWST has become a cultural as well as scientific phenomenon. Each new data release sparks a wave of preprints on arXiv, followed rapidly by explainers on YouTube, Twitter/X, TikTok, and LinkedIn. Color‑coded spectra of exoplanets, redshift distributions of early galaxies, and side‑by‑side comparisons with Hubble images routinely go viral.

Why JWST Captivates the Public

- Visual impact: High‑dynamic‑range, infrared‑rich imagery exposes structures the human eye has never seen.

- Cosmic narrative: Stories about “the first galaxies,” “baby stars,” and “alien atmospheres” naturally lend themselves to compelling storytelling.

- Open data and preprints: Public archives and preprint culture make it possible for enthusiasts to follow cutting‑edge results almost in real time.

Many professional astronomers now maintain active social media presences, publishing threaded explainers that walk through JWST spectra line by line. A good starting point for accessible yet rigorous commentary is the NASA Webb Telescope account on Twitter/X and the NASA Webb YouTube channel.

Milestones: Key Discoveries and Breakthroughs

By early 2026, JWST has already reshaped multiple subfields. Some of the most influential milestones include:

1. Confirmed Record‑Breaking High‑Redshift Galaxies

Spectroscopic confirmation of galaxies at redshifts beyond z ≈ 10 has extended our directly observed horizon closer to the Big Bang than ever before. These systems exhibit vigorous star formation, blue ultraviolet slopes, and in some cases surprisingly mature morphologies.

2. Quantifying Star‑Formation Efficiency in the Early Universe

By combining JWST with ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) and large cosmological simulations, astronomers are:

- Measuring stellar‑to‑halo mass relations at high redshift.

- Assessing how rapidly gas is converted into stars in low‑mass halos.

- Constraining feedback from supernovae and black holes in regulating starbursts.

3. Detailed Characterization of Cloudy, Hazed Exoplanet Atmospheres

JWST has provided multi‑wavelength spectra for a diverse sample of hot Jupiters, warm Neptunes, and sub‑Neptunes. These data show that:

- Clouds and hazes are ubiquitous, muting some spectral features.

- C/O (carbon‑to‑oxygen) ratios vary widely, reflecting formation locations and migration histories.

- Photochemistry and disequilibrium processes must be explicitly modeled to interpret observed spectra.

Challenges: Interpreting a More Complex Universe

JWST is not only answering questions—it is generating new ones. Many early findings have challenged the simplicity of pre‑launch models, forcing theorists to revisit assumptions about star formation, galaxy growth, and planetary atmospheres.

Systematic Uncertainties and Data Complexity

Interpreting JWST data is technically demanding:

- Calibration: Time‑dependent instrument response, detector effects, and contamination from background sources must be carefully modeled.

- Model degeneracies: Different combinations of parameters (e.g., metallicity, dust content, star‑formation history) can reproduce similar spectral energy distributions.

- Selection biases: Bright, unusually compact galaxies are over‑represented in early surveys, skewing naive interpretations of the average galaxy population.

The “Too‑Early, Too‑Massive” Galaxy Debate

Initial photometric analyses suggested galaxies that appeared extremely massive very soon after the Big Bang, sparking headlines about “breaking ΛCDM.” More conservative follow‑up studies, incorporating spectroscopic redshifts and improved stellar population models, have moderated these claims.

“Webb has not overthrown standard cosmology, but it is forcing us to confront the messy details of galaxy formation earlier than we expected.” — Rachel Somerville, theoretical cosmologist

Operational Challenges and Longevity

From an engineering standpoint, JWST has so far exceeded expectations in fuel efficiency and pointing stability. Still, mission planners must:

- Optimize fuel usage for station‑keeping to maximize mission lifetime (currently projected to be 20+ years).

- Continuously monitor micrometeoroid impacts on the primary mirror segments.

- Maintain instrument cryogenic performance, particularly for MIRI.

Milestones in Public Engagement: Tools for Learning From JWST Data

One underappreciated milestone is the maturing ecosystem of tools that allows students, educators, and enthusiasts to interact directly with JWST data.

Educational and Citizen‑Science Platforms

- Mast Portal: The Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes (MAST) hosts JWST datasets; users can search, visualize, and download observations.

- ESA & NASA outreach pages: Provide processed images, explanatory graphics, and teacher resources tailored to various grade levels.

- Citizen‑science projects: Platforms like Zooniverse periodically include JWST‑related projects, such as classifying galaxy morphologies or identifying gravitational lenses.

For readers who want a hands‑on introduction to astronomical image processing and data analysis, an accessible complement is Astronomy for Hackers , which walks through basic techniques used by both amateurs and professionals.

Conclusion: A New Golden Age of Infrared Astronomy

JWST’s early galaxy surveys, exoplanet spectra, and richly detailed images of star‑forming regions confirm that we are in the midst of a new golden age of infrared astronomy. Rather than breaking physics, Webb is exposing the full complexity of galaxy assembly, chemical enrichment, and planet formation that simpler pre‑launch models only hinted at.

Over the next decade, JWST will be complemented by facilities such as the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, and 30‑meter‑class ground‑based telescopes. Together, they will link the earliest galaxies Webb sees to the large‑scale structure we map today, and will place individual exoplanet atmospheres in the broader context of planetary system demographics.

For anyone wishing to follow along, a practical path is:

- Subscribe to the official NASA Webb blog for mission updates.

- Browse the latest Webb‑related papers on arXiv (astro‑ph) .

- Watch expert explainers from channels like PBS Space Time and Anton Petrov , which frequently break down JWST discoveries at a graduate‑level yet accessible depth.

Additional Resources and How to Dive Deeper

To deepen your understanding of JWST and the early universe, consider the following types of resources:

Books and Courses

- Cosmology primers: Texts such as “Introduction to Cosmology” by Barbara Ryden provide the theoretical framework behind Webb’s galaxy and reionization studies.

- Online lecture series: Many universities have posted graduate‑level cosmology and exoplanet courses on YouTube; look for lectures from institutions like MIT, Princeton, and Cambridge for rigorous yet open access content.

Professional and Social Media

Following active researchers offers a front‑row seat to how scientific consensus evolves:

- NASA on LinkedIn for mission‑level updates and career perspectives.

- Individual astronomers on Twitter/X and Mastodon often live‑tweet conferences such as the American Astronomical Society (AAS) meetings, where JWST results are heavily featured.

References / Sources

Selected reputable sources for further reading:

- NASA JWST Mission Page — https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/webb/main/index.html

- ESA Webb Science — https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Space_Science/Webb

- Canadian Space Agency JWST — https://www.asc-csa.gc.ca/eng/satellites/jwst/

- MAST Webb Archive — https://archive.stsci.edu/webb/

- JWST Early Release Science Papers (arXiv collection) — https://arxiv.org/search/astro-ph?query=JWST+Early+Release+Science

- Review on JWST and high‑redshift galaxies (e.g., ARA&A) — https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-astro-032122-105642

- Exoplanet spectroscopy with JWST (Science, Nature Astronomy articles) — https://www.nature.com/subjects/james-webb-space-telescope