Why the Right‑to‑Repair Movement Will Decide the Future of Your Devices

The right‑to‑repair debate has evolved from a niche activist concern to a defining question in consumer technology: when you buy a device, do you truly own it, or are you merely licensing access under strict conditions? As smartphones, laptops, tractors, and smart appliances become more complex—and more locked down—the political, economic, and environmental pressure to make them repairable has intensified.

Technology media such as Ars Technica, The Verge, and Wired now cover right‑to‑repair as a standing beat, tracking legislation, teardown scores, and policy reversals from major manufacturers like Apple, Samsung, Microsoft, and John Deere. Meanwhile, viral teardown videos, DIY guides, and social media discussions have turned repairability into a mainstream consumer expectation, not just an engineering detail.

At stake is device longevity: whether products are designed to last and be maintained, or to be replaced frequently in tightly controlled ecosystems. That choice has profound implications for consumer rights, digital equity, cybersecurity, and the climate.

Mission Overview: What the Right‑to‑Repair Movement Wants

At its core, the right‑to‑repair movement argues that owners and independent repairers should have fair access to:

- Service manuals and diagnostic documentation

- Software diagnostic tools and calibration utilities

- Reasonably priced replacement parts for a reasonable number of years

- Firmware and security updates that do not arbitrarily disable repaired or refurbished devices

“If you can’t fix it, you don’t really own it.” — Kyle Wiens, CEO of iFixit and prominent right‑to‑repair advocate

Early right‑to‑repair activism started in automotive and agricultural sectors, where farmers and mechanics found themselves locked out of diagnostic software for modern vehicles. Over the last decade, the same pattern emerged with smartphones, game consoles, laptops, and even medical devices, driving the expansion of the movement into mainstream consumer tech.

Today, the mission has three tightly linked pillars:

- Consumer autonomy: Ensuring people can maintain and modify devices they bought.

- Competitive repair markets: Allowing independent repair shops to operate without legal or technical barriers.

- Environmental sustainability: Extending device lifespans to reduce e‑waste and resource extraction.

Legislative Landscape: From Grassroots to Global Policy

Over the last few years, right‑to‑repair has shifted from petitions and op‑eds into hard law. While details vary by region, the trend is clearly toward expanded repair access.

United States: State‑Level Momentum and Federal Signals

Several U.S. states have passed or advanced electronics right‑to‑repair laws, often focused on consumer devices:

- New York Digital Fair Repair Act: Requires manufacturers to provide parts, tools, and documentation for certain electronic products sold in the state.

- California and Minnesota: Enacted broad right‑to‑repair measures covering a wide range of consumer electronics.

- FTC and White House: The U.S. Federal Trade Commission has publicly committed to enforcing existing laws against repair restrictions, following a 2021 executive order urging support for right‑to‑repair.

Policy analysts track these changes closely in outlets like The Verge’s tech policy coverage and Electronic Frontier Foundation’s right‑to‑repair briefings.

European Union: Eco‑Design and Repairability as a Service Requirement

The EU has been particularly aggressive, treating repairability as part of its circular economy and climate agenda:

- Regulations mandating spare parts and repair information for some appliances and electronics.

- A proposed “Right to Repair” directive requiring manufacturers to offer repair when it is cheaper than replacement under warranty and to provide access to repair information long after sale.

- Repairability and durability scoring schemes, similar to France’s repairability index, which publicly rate products on how easy they are to fix.

Global Agriculture and Heavy Equipment

In agriculture, landmark settlements and policy moves have pressured companies like John Deere to open up diagnostic tools to farmers and independent technicians, addressing concerns that software locks were effectively disabling self‑repair on essential equipment.

“Digital locks on hardware are no longer a marginal annoyance; they are a systemic governance issue for critical infrastructure and food systems.” — Paraphrased from analysis in Nature on digital ownership and repair.

Technology: How Design Choices Shape Device Longevity

Repairability is not an abstract ideal; it is embedded in specific design and engineering decisions. Every product release reflects trade‑offs between thinness, durability, water resistance, cost, manufacturing complexity, and future serviceability.

Hardware Design Features that Affect Repairability

- Fasteners: Standard screws dramatically improve repair; proprietary screws or permanent rivets hinder it.

- Adhesives vs. clips: Excessive glue makes batteries and screens difficult and risky to remove; mechanical clips or pull‑tabs are more service‑friendly.

- Modular vs. soldered components: Soldered RAM or storage reduces part count and thickness but makes upgrades impossible.

- Paired components: Serial‑number pairing of parts (camera modules, screens, batteries) to specific logic boards can electronically block otherwise successful repairs.

- Diagnostic ports and software: Proprietary tools may be required to calibrate cameras, Face ID sensors, or battery indicators after replacement.

Benchmarking work by iFixit’s repairability scores and teardowns by outlets like TechRadar have made these design details highly visible to buyers.

Software Locks and Firmware Control

Even when a device is physically repairable, software can be used to discourage or disable third‑party service:

- Component authentication: Devices may refuse to accept genuine parts unless they are programmed via proprietary tools.

- Error messages: Persistent warnings can deter users from third‑party or self‑repair even when functionality is normal.

- Cloud‑tied activation: Activation servers and account locks can brick devices that were otherwise repairable and resellable.

Manufacturers argue that such measures are sometimes needed to protect user data and maintain safety; critics respond that they often overshoot, serving as effective monopolies on repair.

Scientific Significance and Environmental Impact

From a systems perspective, the right‑to‑repair movement is an intervention in material and energy flows through the global electronics lifecycle. Extending device lifetime is among the most effective ways to cut emissions associated with manufacturing.

Life‑Cycle Assessment (LCA) Findings

Peer‑reviewed life‑cycle assessments consistently show that:

- The majority of a smartphone’s carbon footprint—often 70–80%—is embedded in manufacturing.

- Using a phone for five to seven years instead of two to three can materially lower its annualized emissions.

- Refurbishment and reuse are often more climate‑efficient than recycling, which, while essential, still consumes energy and loses material quality.

“The greenest device is the one you already own.” — A phrase frequently cited in EU circular‑economy briefings and repair advocacy.

Resource Extraction and Critical Materials

Modern electronics rely on critical minerals—cobalt, lithium, rare earth elements—whose extraction raises environmental and human‑rights concerns. A longer device lifespan:

- Reduces demand for newly mined materials.

- Buys time to improve mining standards and recycling efficiency.

- Improves resilience against supply shocks in critical raw materials.

Environmental reporting by outlets like Nature and Science increasingly highlight repair and reuse as core strategies in climate mitigation.

Industry Response: Self‑Service Programs and Repair‑Friendly Designs

Large manufacturers have begun to adapt their policies and designs under regulatory and consumer pressure, though often in carefully bounded ways.

Self‑Service Repair and Authorized Networks

Companies like Apple, Samsung, and Microsoft have launched self‑service repair portals and expanded authorized repair networks. These programs typically:

- Provide access to genuine parts and rental of professional‑grade tools.

- Offer detailed step‑by‑step guides for specific repairs.

- Require serial‑number checks and may still bind parts to devices via software.

Coverage by Wired and Ars Technica often notes that these programs are meaningful steps forward but still fall short of full parity for independent shops.

Repair‑First Product Lines: Framework and Fairphone

A new generation of hardware startups treats repairability as a core feature, not an afterthought:

- Framework Laptop: A modular laptop with user‑replaceable mainboard, ports, keyboard, and screen, documented openly and shipped with standard fasteners.

- Fairphone: A smartphone with easily swappable battery, modular camera and display, and long‑term software support commitments.

These devices frequently score at or near the top of iFixit repairability rankings, serving as proof‑of‑concept that modern aesthetics and strong performance can coexist with modular, serviceable design.

Milestones: Key Moments in the Right‑to‑Repair Story

The movement’s trajectory can be traced through a series of widely covered events and policy breakthroughs.

Notable Milestones

- Early 2010s: Automotive right‑to‑repair laws and agreements in the U.S. set precedents for access to diagnostic tools.

- 2015–2020: Viral teardown videos and the rise of iFixit’s scoring system turn repairability into a consumer talking point.

- 2021: U.S. federal signals in favor of right‑to‑repair; FTC pledges enforcement; EU deepens eco‑design regulations.

- 2022–2024: State‑level laws in New York, Minnesota, California and others; agriculture settlements broaden access to farm equipment diagnostics.

- Rise of modular hardware: Framework and Fairphone demonstrate commercial viability of repair‑centric products.

Each of these milestones provoked extensive coverage in technology media and discussion in communities like Hacker News, Reddit’s repair forums, and specialized repair YouTube channels.

Challenges and Trade‑Offs: Security, Safety, and Business Models

Despite growing momentum, right‑to‑repair faces real technical, legal, and economic complexities. The debate is not simply “open everything” versus “lock everything down.”

Security and Privacy Concerns

Manufacturers often cite security and privacy when resisting open repair:

- Biometric sensors (e.g., Face ID) must be carefully paired to prevent spoofing or unauthorized access.

- Encrypted storage and secure enclaves complicate data‑preserving repairs or board swaps.

- Malicious parts or compromised firmware could create attack vectors.

“Security and maintainability are not opposites; when done right, they reinforce each other. The problem is when control mechanisms are misused to block owners instead of attackers.” — Paraphrasing security technologist Bruce Schneier’s broader arguments on security and device control.

Advocates argue that the answer is not secrecy but robust, well‑documented processes for secure repair that independent technicians can follow under appropriate regulations and certifications.

Engineering Trade‑Offs: Thinness vs. Repairability

Some design tensions are genuine:

- Ultra‑thin devices leave less room for modular connectors, making soldered components tempting.

- High water‑resistance ratings may favor adhesive‑heavy construction.

- Cost constraints can push manufacturers toward integrated “all‑in‑one” boards instead of socketed components.

However, examples like Framework and Fairphone demonstrate that well‑chosen trade‑offs can preserve both durability and user serviceability, especially when repairability is considered from the earliest design phases.

Business Model Inertia

Many established companies still rely on:

- Frequent new device cycles to drive revenue.

- High‑margin repair services offered through exclusive channels.

- Accessory and ecosystem lock‑in to retain customers.

Transitioning to a world of durable, repairable devices may require new revenue models—extended support contracts, subscription services, certified refurbished programs—that reward longevity instead of obsolescence.

The Consumer Perspective: Practical Steps to Extend Device Life

For individual users, right‑to‑repair is not only a policy issue; it is a set of actionable strategies to keep devices running longer and reduce costs.

Before You Buy: Evaluating Repairability

- Check independent repairability scores and teardowns (e.g., iFixit, specialized YouTube channels).

- Look for modular designs, standard screws, and publicly available manuals.

- Consider total cost of ownership, including likely repairs and battery replacements.

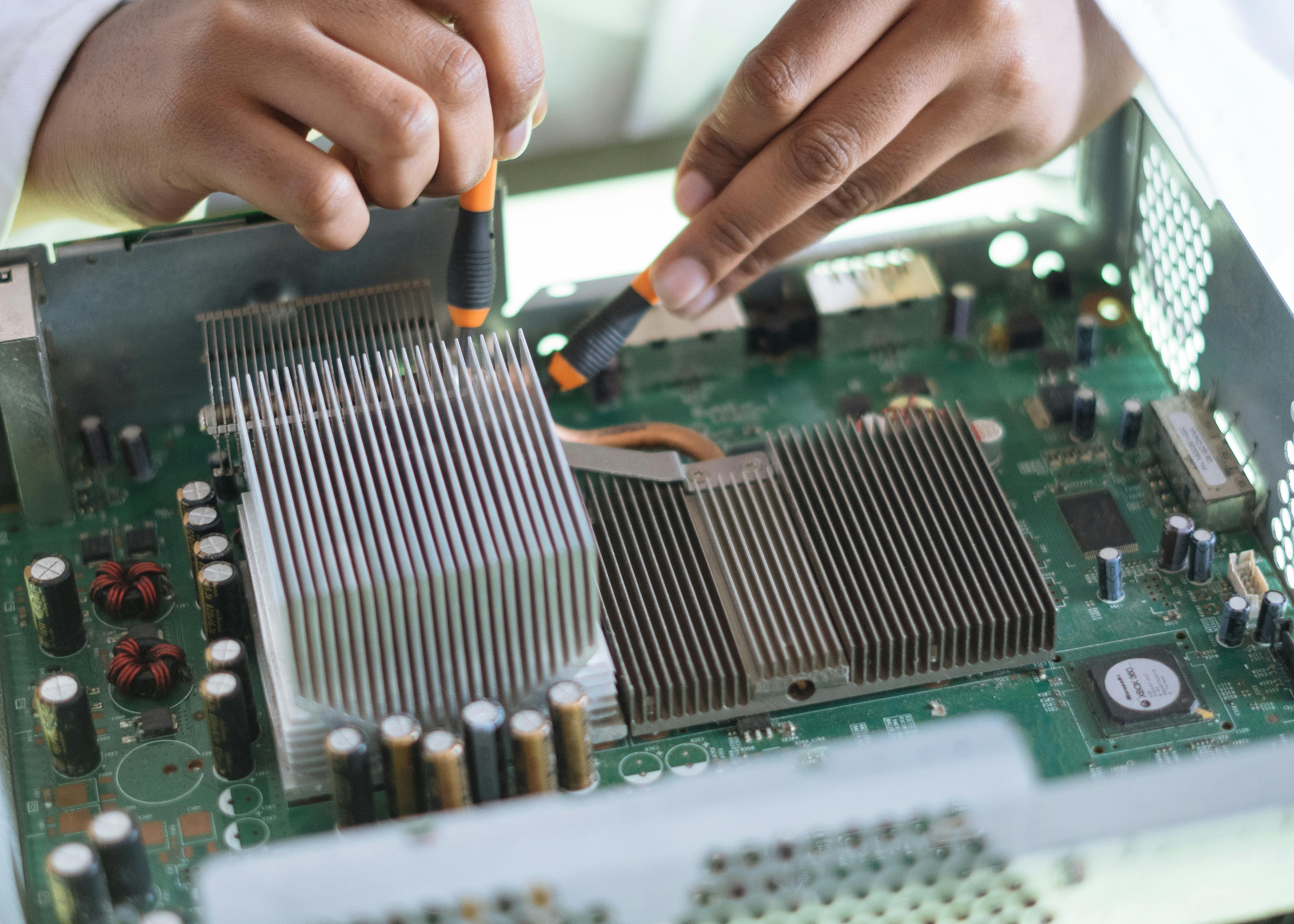

During Ownership: Maintenance and DIY Repairs

With basic tools and guidance, many repairs are accessible to non‑experts:

- Battery replacements for phones and laptops

- Storage or RAM upgrades (where hardware allows)

- Fan cleaning and thermal paste refresh on laptops and desktops

Quality tools significantly reduce the risk of damage. For example, precision screwdriver kits like the iFixit Morro 32‑bit Precision Screwdriver Set are popular among repair hobbyists and professionals for safely opening modern electronics.

Learning Resources

A rich ecosystem of free educational material has grown up around repair:

- iFixit repair guides for phones, laptops, appliances, and more.

- YouTube channels such as Louis Rossmann’s board‑level repair videos and other device‑specific creators.

- Community forums on Reddit, specialized Discord servers, and independent blogs focused on device longevity.

Conclusion: Who Owns Your Devices’ Future?

The right‑to‑repair movement forces a fundamental question: ownership or rental? If devices are sealed, locked, and controlled remotely, long after purchase, then the traditional notion of owning hardware erodes into something closer to a subscription relationship—without the transparency of a subscription.

By contrast, repairable devices—with accessible parts, documentation, and software tools—support a healthier ecosystem: local repair jobs, lower e‑waste, longer lifespans, and empowered users. The transition will not be frictionless; it touches security engineering, industrial design, logistics, and corporate earnings. But each regulatory win, each repair‑friendly product, and each successful DIY fix nudges the market toward a more sustainable, user‑centric equilibrium.

For consumers, the most effective actions are:

- Choosing repairable products.

- Supporting companies and legislation that prioritize repair rights.

- Investing in basic tools and skills to maintain what you already own.

Device longevity is no longer a niche concern; it is a central axis along which the future of consumer technology will be decided.

Additional Insights: How Right‑to‑Repair Intersects with Emerging Tech

As new technologies mature, right‑to‑repair considerations are surfacing earlier in the design cycle.

AI Devices, AR/VR Headsets, and Wearables

AI‑enhanced devices, mixed‑reality headsets, and advanced wearables pack more sensors and specialized chips into smaller enclosures, often at the expense of repairability. Early teardowns of next‑generation headsets and smart glasses show heavy use of adhesives and custom flex cables that complicate service.

Expect future debates to focus on:

- Battery replacement in tightly integrated wearable systems.

- Camera and sensor calibration tools for AR/VR headsets.

- Ethical and privacy implications of making sensor‑rich devices easy—or hard—to refurbish.

Enterprise and Cloud‑Managed Hardware

In corporate environments, cloud‑managed laptops and IoT devices blur the line between hardware ownership and service subscription. While enterprises may accept centralized control, the same patterns applied to personal devices raise difficult questions about autonomy and after‑market use.

For professionals and IT departments, repair‑friendly business‑class hardware, such as modular laptops and servers with well‑documented field‑replaceable units, can significantly reduce downtime and total cost of ownership.

References / Sources

Further reading and sources on the right‑to‑repair movement and device longevity:

- iFixit – Right to Repair overview

- The Verge – Right‑to‑repair coverage

- Wired – Right‑to‑repair articles

- FTC – “Nixing the Fix” report on repair restrictions

- European Commission – EU Right to Repair initiative

- Nature – Opinion pieces on digital ownership and repair

- Louis Rossmann – Independent repair advocacy and resources

- Hacker News – Ongoing community discussions on repairability