What Connecticut’s First Measles Case in 4 Years Means for Your Family (And How to Stay Safe)

Connecticut has reported its first measles case in more than four years, diagnosed in an unvaccinated Fairfield County child who recently traveled overseas. This article explains what this case means for families, how measles spreads, what symptoms to look for, and how vaccination and practical precautions can help protect your children and community.

Connecticut’s First Measles Case in Years: What Parents Need to Know Right Now

When you hear “measles,” it can sound like a disease from another era—something your grandparents worried about, not you. Yet public health officials in Connecticut have just confirmed the state’s first measles case in more than four years: a Fairfield County child under 10 who was not vaccinated and had recently traveled overseas.

If you’re a parent or caregiver, it’s completely understandable to feel uneasy. You might be wondering: Is my child at risk? What should I look for? Is it too late to get protected? Let’s walk through the facts, the science, and practical steps you can take today—without panic, but with clear-eyed caution.

What We Know About the Fairfield County Measles Case

As reported by Connecticut health officials and local media, here are the essential details that have been made public:

- The child is under 10 years old.

- The child was not vaccinated against measles.

- They had recently traveled overseas, where measles circulation is higher in some countries.

- Symptoms started a few days after returning, including:

- Cough

- Runny nose and congestion

- Fever

- Followed by a characteristic rash

- The Connecticut Department of Public Health is contact tracing and identifying potential exposure locations.

“Measles is one of the most contagious diseases in the world. However, it is preventable through a safe and effective vaccine.”

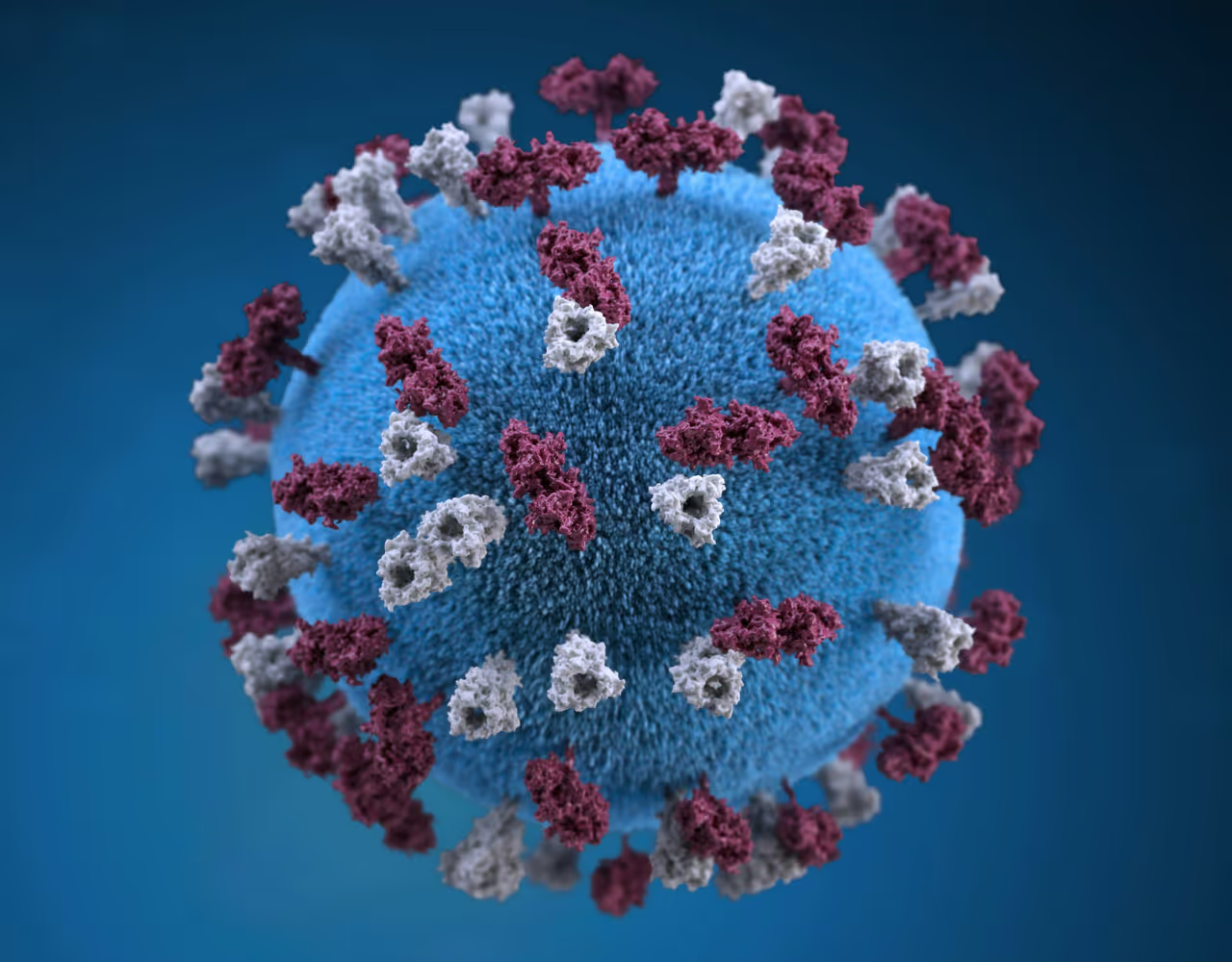

A Quick Refresher: What Is Measles and Why Does It Matter?

Measles is a viral infection that spreads through the air when an infected person breathes, coughs, or sneezes. The virus can linger in the air and on surfaces for up to two hours. Because of that, measles is often described as “ultra-contagious.”

Before vaccines became common, measles caused millions of infections and many deaths worldwide each year. Vaccination has dramatically reduced cases in the United States—but outbreaks can still occur when:

- People travel to or from countries where measles is circulating, and

- Local vaccination rates are low enough for the virus to spread.

Measles Symptoms: What to Watch for After Possible Exposure

In this Connecticut case, the child developed a cough, runny nose, congestion, fever, and then a rash—a classic progression. Here’s how measles usually unfolds:

- Days 1–3: High fever (often 101°F or higher), cough, runny nose, and red, watery eyes.

- Days 2–4: Tiny white spots (Koplik spots) may appear inside the mouth, though these can be easy to miss.

- Days 3–5: A red, blotchy rash starts on the face and hairline, then spreads down the body.

- Contagious window: From about 4 days before the rash appears until 4 days after it begins.

Symptoms usually begin 7–14 days after exposure but can occasionally appear up to 21 days later. If your child has these symptoms and may have been exposed, call your pediatrician or clinic before arriving so they can protect other patients.

How Measles Spreads: Why One Case Can Matter for a Whole Community

Measles is not like a typical cold. If one person has measles, up to 9 out of 10 unvaccinated people close to them can become infected if they are not immune.

The virus can spread when:

- An infected person coughs, sneezes, or even talks.

- You share the same airspace with them within about two hours of their presence.

- You touch a contaminated surface and then touch your mouth, nose, or eyes.

This is why public health teams move quickly after a confirmed case—to notify potentially exposed people and check who is already protected through vaccination or past infection.

MMR Vaccine: How It Protects Children and Communities

The main tool we have to prevent measles is the MMR vaccine, which protects against Measles, Mumps, and Rubella. It has been used for decades and is strongly supported by global health organizations.

Standard MMR Schedule in the U.S.

- First dose: 12–15 months of age

- Second dose: 4–6 years of age (can be given earlier in some situations, at least 28 days after dose one)

According to the CDC and World Health Organization:

- One dose is about 93% effective at preventing measles.

- Two doses are about 97% effective.

“Widespread use of measles vaccine has led to a 73% drop in measles deaths globally between 2000 and 2018.”

Is It Too Late If You’ve Delayed MMR?

In most cases, it’s not too late. Even if your child missed the recommended age, they can often “catch up” on MMR doses. Your healthcare provider can review your child’s record and create a schedule that makes sense for your family and any recent exposures or travel.

Travel and Measles: Lessons from the Fairfield County Case

In this Connecticut case, the child’s infection was linked to recent international travel. This pattern is common: many U.S. measles outbreaks begin when an unvaccinated traveler is exposed abroad and brings the virus home.

Before You Travel with Children

- Check vaccination status early.

Review your child’s vaccination record at least 4–6 weeks before your trip. - Consider early MMR for infants (when appropriate).

For some international travel, CDC allows MMR for infants 6–11 months. This is a special situation and does not replace the regular two-dose schedule; your pediatrician can guide you. - Know your destination’s measles situation.

Check resources like the CDC’s Travelers’ Health page to see if measles is circulating where you’re going.

Common Concerns About the Measles Vaccine—and Compassionate Ways to Address Them

If you’ve delayed or avoided the MMR vaccine, you’re not alone. Parents often share worries like:

- “I’m worried about side effects or long-term risks.”

- “There’s so much conflicting information online.”

- “We don’t usually vaccinate unless it’s absolutely necessary.”

These fears are real and deserve respectful, evidence-based answers—not judgment. Large, high-quality studies from multiple countries have consistently found no link between MMR and autism, and serious side effects are rare. At the same time, measles itself can cause long-term harm, including brain injury and death in a small percentage of cases.

“In my practice, I’ve seen how parents’ anxiety melts when they’re given space to ask hard questions without being dismissed. Feeling heard is often the first step toward feeling safe about vaccines.”

Practical Ways to Move from Fear to Informed Choice

- Schedule a “questions-only” visit. Let your pediatrician know you want time just to talk about vaccines—not to be rushed.

- Use trusted sources. Sites like the CDC Vaccine Safety pages and HealthyChildren.org (from the American Academy of Pediatrics) summarize research in parent-friendly language.

- Ask about your family’s specific risks. Factors like travel plans, school environment, immune conditions, and pregnancy can all shape what’s recommended.

Action Plan: How to Protect Your Family Today

Here are practical, evidence-informed steps you can take in light of Connecticut’s measles case, especially if you live in Fairfield County or nearby regions.

Step 1: Check Vaccination Records

- Locate your child’s immunization card or online patient portal.

- Look specifically for MMR or combined vaccines like MMRV.

- Note which doses they’ve received and the dates.

Step 2: Call Your Healthcare Provider If

- Your child is missing one or both MMR doses.

- You’re pregnant and unsure of your measles immunity.

- You or your child recently traveled internationally.

- You’ve been in locations or events that public health officials later identify as exposure sites.

Step 3: Monitor Symptoms Thoughtfully

If your child develops fever, cough, runny nose, and then a rash—especially within 7–21 days of travel or a known exposure:

- Call your clinic first to explain symptoms and any exposure.

- Follow their instructions about where to go and how to enter the building safely.

- Try to avoid crowded public places until you’ve spoken with a clinician.

Visual Snapshot: Measles Risk vs. Vaccine Protection

Here’s a quick comparison to put the Fairfield County case into perspective. Think of it as a “before and after” of what happens when a community embraces vaccination:

Before (Low Vaccination)

- One measles case can infect many unvaccinated people.

- Higher chance of school and daycare outbreaks.

- Increased risk for babies, pregnant people, and those with weak immune systems.

- More hospitalizations and rare but serious complications.

After (High Vaccination)

- One imported case is less likely to spread widely.

- Schools and community spaces are safer overall.

- Vulnerable people benefit from community protection.

- Fewer disruptions to childcare, school, and work.

Measles will likely remain a risk as long as it circulates globally—but local vaccination can make the difference between a single contained case and a community-wide outbreak.

Moving Forward: Stay Calm, Stay Informed, and Take the Next Right Step

Hearing that a child in Fairfield County has been diagnosed with measles—Connecticut’s first case in years—can feel unsettling, especially if you’re caring for young kids. But it can also be a turning point: a reminder to check records, ask questions you’ve been postponing, and strengthen your family’s protection.

You don’t have to overhaul everything at once. Focus on the next right step for your situation:

- Look up your child’s MMR status.

- Write down your top 3 vaccine questions.

- Make a short phone appointment with your pediatrician or clinic.

- Keep an eye on official public health updates, not rumors.

With clear information, a trusted healthcare partner, and timely action, most families can navigate situations like this with confidence rather than fear.

Disclaimer: This article is for general informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the guidance of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or vaccine decision.