Sam Altman Says Gen Z Could Land High-Paid Space Jobs by 2035 as AI Transforms Work

OpenAI chief executive Sam Altman has forecast that by around 2035, some college graduates could leave school for “completely new, exciting, super well-paid” jobs in space exploration, even as artificial intelligence (AI) displaces parts of today’s workforce and forces Gen Z to rethink traditional career paths. His comments, made in a conversation with video journalist Cleo Abram, come amid broader debate among technology leaders about whether AI will usher in shorter workweeks, amplify human capabilities, or render large categories of work obsolete.

Sam Altman’s vision: Graduates working in space by 2035

In a recent interview with Cleo Abram, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman described a future in which young professionals may begin their careers far beyond Earth. Altman suggested that, within about a decade, advances in AI and related technologies could make space-based roles a realistic option for some graduates.

“In 2035, that graduating college student, if they still go to college at all, could very well be leaving on a mission to explore the solar system on a spaceship in some completely new, exciting, super well-paid, super interesting job,” Altman told Abram, according to the published interview.

Altman framed these hypothetical space careers not only as lucrative but also as more stimulating than many current entry-level roles. He said he believed future workers might “feel so bad” for earlier generations who had to perform “really boring, old work,” arguing that AI could automate much of today’s routine labor and open space for more ambitious projects, including off-world exploration.

Despite his optimism, Altman acknowledged he does not know exactly how AI will evolve. He described the technology’s trajectory as uncertain but still called this era “the most exciting time in history to start a career.” “If I were 22 right now and graduating college, I would feel like the luckiest kid in all of history,” he told Abram.

AI disruption: Gen Z faces an unstable job market

Altman’s space-focused remarks arrive as many Gen Z graduates confront a more immediate challenge: navigating a job market reshaped by AI tools that can perform tasks once reserved for human workers. From writing and design to customer support and basic coding, AI systems have begun to automate functions in white-collar and creative fields.

Altman has repeatedly acknowledged that this transformation will eliminate some kinds of work. In his conversation with Abram, he conceded that “AI will wipe out some jobs entirely,” echoing earlier statements he has made in public forums about the disruptive potential of advanced models produced by OpenAI and other firms.

Economists and labor analysts are divided on how quickly these changes will manifest. Some studies from international organizations such as the OECD and the International Labour Organization have warned that a significant share of tasks across many occupations is highly automatable, while also noting that new roles and industries typically emerge alongside major technological shifts. Others argue that AI’s full impact may take longer to materialize, giving institutions more time to adapt education, training, and social protections.

For now, many young workers report what career advisers describe as an “existential” anxiety: degrees obtained just a few years ago may not align with the jobs that will be in demand by the mid-2030s, and there is limited consensus among experts about which skills will prove most resilient.

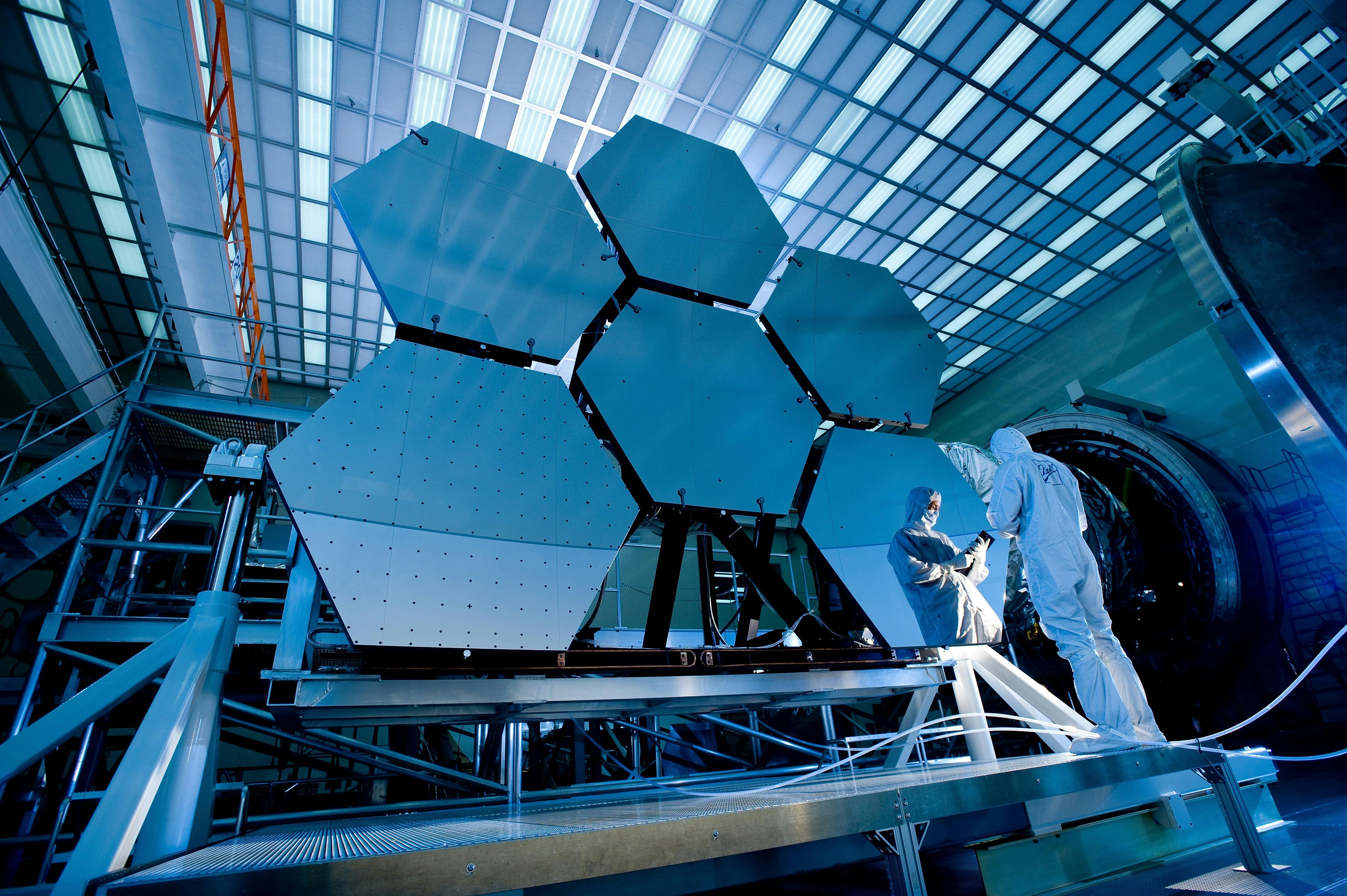

Space careers today: Limited but growing opportunities

While Altman’s scenario of graduates boarding spaceships to explore the solar system remains speculative, there is measurable growth in space-related employment. Government agencies such as NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), and emerging national programs, as well as private companies like SpaceX, Blue Origin, and others, have increased hiring for roles tied to launch systems, satellite constellations, and deep-space missions.

Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) indicate that employment for aerospace engineers is projected to grow faster than the average for all occupations over the coming decade. According to the BLS, median annual pay for aerospace engineers in the United States exceeds US$130,000, placing these roles among the higher-earning engineering specialties.

NASA has publicly discussed aspirations to send crewed missions to Mars sometime in the 2030s, though timelines remain subject to technical, budgetary, and political challenges. In parallel, commercial operators are developing vehicles aimed at commercial crew flights, space tourism, and cargo services to low Earth orbit and beyond. Analysts note that a sustained expansion of human activity in space would likely create additional demand not only for engineers and astronauts but also for specialists in life support systems, in-space manufacturing, communications, and safety.

However, experts caution that space work is unlikely to become a mass-employment sector in the near term. Access to such jobs typically requires advanced degrees in STEM fields, specialized training, and the capacity to meet stringent medical and security standards. For most graduates in 2035, work is still expected to take place on Earth, even if their roles are increasingly intertwined with space-based infrastructure and data.

How AI may reshape the workplace on Earth

Other technology leaders paint a less extraterrestrial, but still transformative, picture of the future of work. Microsoft cofounder Bill Gates has argued that AI could significantly shorten the typical workweek by taking over many routine tasks. In a televised appearance on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, Gates mused about whether societies might eventually settle on working “two or three days a week” as automation spreads.

Gates’ remarks build on a longer tradition of predictions that productivity gains from technology could one day allow people to enjoy more leisure time without sacrificing living standards. Whether this outcome materializes depends on policy choices, labor bargaining power, and how the benefits of AI are distributed between capital and workers.

Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang, whose company designs the chips that power many AI systems, emphasizes a different dynamic. In a separate interview with Cleo Abram, Huang said that AI tools have already given his employees “superhuman” abilities by amplifying what top specialists can achieve. He described working alongside experts whose performance, when combined with advanced computing, appears to him as “super intelligence.”

“I’m surrounded by superhuman people and super intelligence, from my perspective, because they’re the best in the world at what they do. And they do what they do way better than I can do it. And I’m surrounded by thousands of them. Yet it never one day caused me to think, all of a sudden, I’m no longer necessary,” Huang said, arguing that even highly capable AI and human colleagues do not eliminate his own role.

Huang’s framing reflects a view shared by some technologists and management scholars: that AI is more likely to reconfigure jobs than replace them entirely, shifting responsibilities toward higher-level decision-making, oversight, and creative problem-solving. Under this model, AI systems handle repetitive or computationally intensive tasks, while humans focus on judgment, ethics, and interpersonal relationships.

Competing visions and what they mean for Gen Z

Altman, Gates, and Huang present overlapping but distinct narratives about AI’s impact. Altman underscores both the threat of job elimination and the potential for entirely new categories of work, including space-based careers. Gates highlights the prospect of reduced working hours and more leisure as AI assumes “most” tasks. Huang stresses augmentation, describing AI as a force that enhances, rather than replaces, human expertise.

Labor researchers point out that all three scenarios could unfold simultaneously in different sectors and regions. High-income, highly educated workers may be more likely to experience AI as a productivity booster and gateway to novel opportunities, including in emerging fields such as commercial space operations or advanced robotics. Workers in roles that are easily automated, by contrast, may face displacement and need reskilling or social support.

For today’s students and recent graduates, this means planning for careers that are more fluid than those of previous generations. Career counselors and education specialists frequently recommend building adaptable skills such as critical thinking, data literacy, and cross-disciplinary collaboration, alongside technical competencies in areas like AI, software, and systems engineering for those interested in technology and space.

Policymakers and institutions will likely play a decisive role in determining whether AI-driven productivity and new industries, including space-related sectors, translate into broader prosperity. Debates continue over proposals such as expanded workforce training, portable benefits, and safety nets designed for an era of more frequent career transitions.

Context, sources, and ongoing debate

Altman’s comments to Cleo Abram form part of a wider public conversation about AI and the future of work. Abram, a video journalist known for her explanatory reporting on technology, has interviewed several high-profile figures on these topics, including Altman and Huang, for her online series Huge If True and related projects.

Gates’ remarks on shortened workweeks were made in a lighthearted exchange on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, but align with more detailed essays he has published about AI’s potential to transform productivity. Huang’s statements have appeared both in his discussion with Abram and in keynote talks tied to Nvidia’s developer and investor events, where he regularly describes AI as a “new industrial revolution.”

Independent analyses from academic institutions, think tanks, and international organizations offer a range of projections, from optimistic scenarios in which AI boosts wages and reduces drudgery, to more cautious outlooks that emphasize inequality and the risk of job polarization. Many experts stress that historical comparisons—to the industrial revolution, electrification, or the rise of the internet—suggest that technology tends to create new categories of work even as it destroys others, but the transition can be uneven and disruptive.

As of late 2025, no major space agency or private company has announced a program in which large numbers of freshly graduated students would immediately depart on multi-year missions across the solar system. Altman’s timeline and description, while grounded in real trends in aerospace and AI, are best understood as a bold forecast rather than a concrete plan.

Outlook: A decade of uncertainty and possibility

As AI capabilities advance and space agencies pursue ambitious exploration goals, projections like Altman’s highlight both the uncertainty and the possibility facing today’s students. The coming decade could see new types of work emerge in orbit and on the ground, even as established roles are redefined or phased out.

Whether 2035 graduates are boarding spacecraft, enjoying shorter workweeks, or collaborating daily with AI systems that feel “superhuman,” the future of work is likely to look markedly different from the early careers of previous generations. The extent to which that future is widely shared—and how many people benefit from high-paid opportunities in sectors like space and advanced computing—remains an open question that governments, employers, and workers are still racing to answer.