Room‑Temperature Superconductivity Reboot: What Really Happened After LK‑99 and the Hydride Retractions?

Superconductivity—the state in which a material conducts electricity with effectively zero resistance and expels magnetic fields via the Meissner effect—has long been one of physics’ most tantalizing phases of matter. For over a century, its practical impact has been constrained by a brutal requirement: extreme cooling, often to just a few kelvin above absolute zero, with liquid helium or advanced cryocoolers.

In the 2010s and early 2020s, a series of claims about “high‑pressure hydride” superconductors seemed to change everything. Sulfur hydride, lanthanum hydride, carbonaceous sulfur hydride, and later lutetium hydride were reported to reach superconducting transition temperatures (\(T_c\)) near or even above room temperature—but only under pressures comparable to those at Earth’s core. Many of the most spectacular results, including the 2023–2024 lutetium hydride paper, were later retracted or heavily disputed due to irreproducible data and problematic analysis.

At nearly the same time, the LK‑99 episode—built around a copper‑doped lead‑apatite compound claimed to be a room‑temperature, ambient‑pressure superconductor—went viral across X/Twitter, YouTube, TikTok, and Reddit. Within weeks, experts demonstrated that LK‑99 was not superconducting; its behavior was consistent with a poor, inhomogeneous conductor showing ferromagnetism and structural quirks.

“The LK‑99 story is not a failure of science, but an accelerated case study of how science self‑corrects in the age of social media.” — Paraphrasing multiple condensed‑matter physicists commenting in Nature coverage.

As of late 2025, the result of these episodes is not the end of the room‑temperature dream but a reboot. The field has pivoted toward more cautious, transparent, and collaborative approaches—while theorists and experimentalists explore new materials platforms from hydrides and nickelates to twisted multilayers and topological systems.

Mission Overview: The Quest for Room‑Temperature Superconductivity

The overarching mission is clear: discover a material that:

- Is truly superconducting (zero resistance and genuine Meissner effect)

- Works at or near room temperature (say 250–300 K or higher)

- Operates at or near ambient pressure (1 bar, not hundreds of gigapascals)

- Is chemically and mechanically stable, scalable, and manufacturable

Such a breakthrough would have profound implications:

- Power infrastructure: Nearly lossless long‑distance electricity transmission, compact power lines, and more efficient transformers.

- Transportation: Practical magnetic‑levitation (maglev) systems without expensive cryogenics; quieter, more efficient motors and generators.

- Medical and scientific imaging: Lighter, cheaper high‑field MRI and NMR systems.

- Quantum technologies: More robust superconducting qubits and scalable cryo‑infrastructure for quantum computing.

- High‑energy devices: Compact fusion magnets, particle accelerators, and high‑field laboratory magnets.

The key constraint is that each claimed breakthrough must now pass a much higher bar of evidence than before the hydride and LK‑99 controversies.

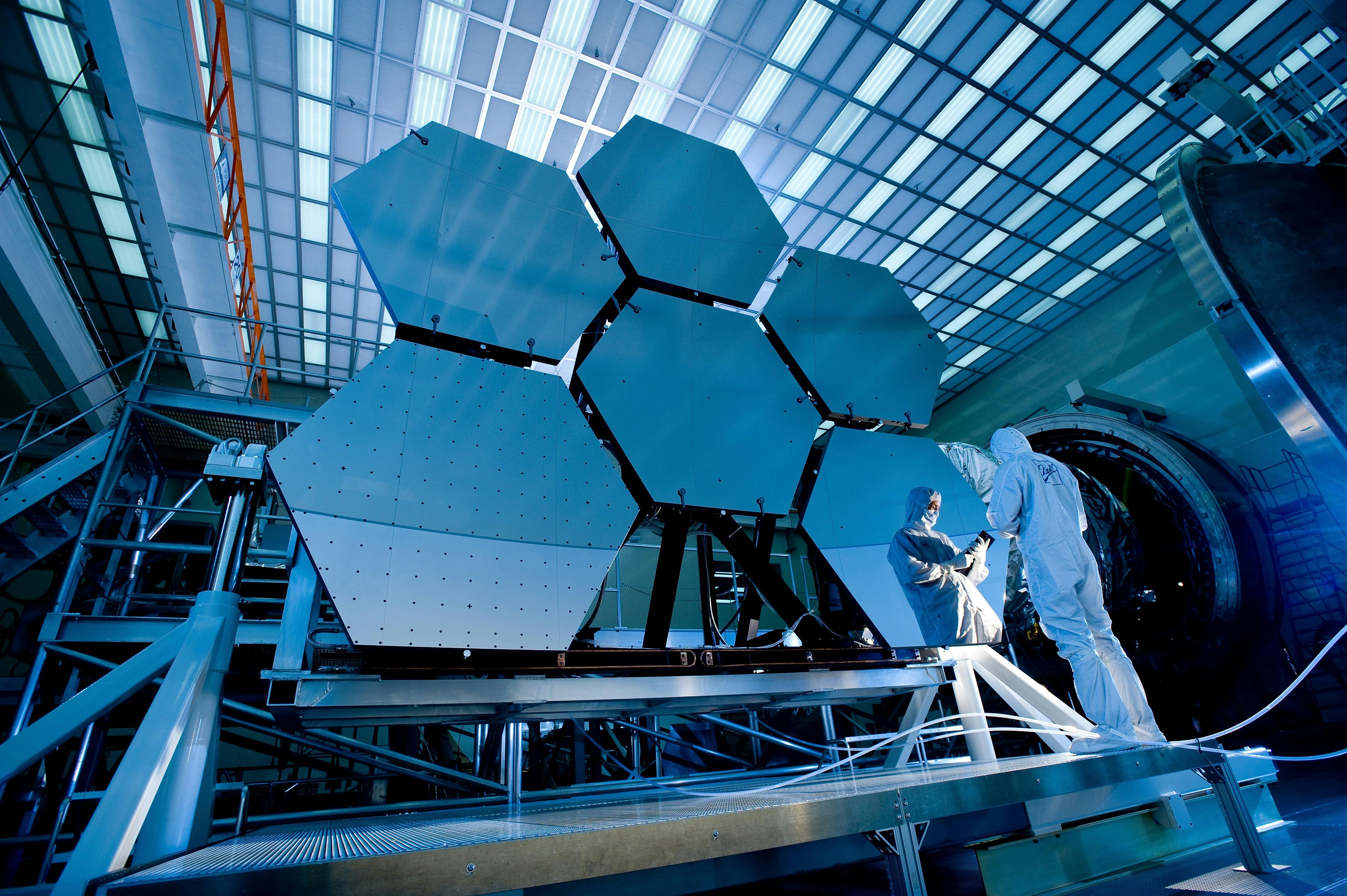

Visualizing the Superconductivity Reboot

Technology: How Modern Superconductivity Research Actually Works

Superconductivity emerges from the collective behavior of electrons in a periodic lattice. In conventional superconductors, the Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer (BCS) theory describes how electrons form bound Cooper pairs mediated by phonons—quanta of lattice vibrations. High‑pressure hydrides push this mechanism to extremes: strong electron–phonon coupling plus high phonon frequencies in light‑element lattices can yield very high \(T_c\) values, according to Migdal–Eliashberg theory.

Key Material Platforms Under Study

- High‑pressure hydrides: Systems like H\(_3\)S and LaH\(_{10}\) show superconductivity above 200 K under hundreds of gigapascals, confirmed by multiple groups. They are proofs‑of‑principle that room‑temperature superconductivity is possible in nature, albeit under extreme conditions.

- Nickelates: Infinite‑layer nickelates (e.g., Nd\(_{0.8}\)Sr\(_{0.2}\)NiO\(_2\)) discovered in 2019 resemble cuprate superconductors but with nickel in place of copper. They may bridge conventional and unconventional pairing mechanisms.

- Twisted multilayer systems: “Twistronics” in bilayer and trilayer graphene and related materials tunes flat bands and strong correlations, sometimes leading to superconductivity at relatively high temperatures (though not yet close to room temperature).

- Topological and multiband systems: Materials with nontrivial band topology or multiple Fermi surfaces may host exotic pairing states, including potential routes to fault‑tolerant topological quantum computing.

Core Experimental Techniques

To claim genuine superconductivity, researchers now typically combine several measurements:

- Four‑probe resistivity: Demonstrating a sharp drop to effectively zero resistance, with well‑characterized contact geometry.

- Magnetic susceptibility: Evidence of the Meissner effect (flux expulsion) and shielding fractions compatible with bulk, not just filamentary, superconductivity.

- Specific heat and thermodynamic probes: A phase transition at \(T_c\) in heat capacity or related quantities.

- High‑pressure techniques: Diamond anvil cells and synchrotron X‑ray diffraction to map structure under extreme conditions.

- Spectroscopy: Angle‑resolved photoemission (ARPES), tunneling spectroscopy, and muon spin rotation to probe the gap structure and pairing symmetry.

“Multiple, independent signatures are essential before we can confidently label a material ‘superconducting’—especially when the claimed \(T_c\) is extraordinary.” — Paraphrasing guidance from review articles in Reviews of Modern Physics.

Machine Learning and Data‑Driven Materials Discovery

One of the most transformative additions to the superconductivity toolkit since 2020 has been data‑driven materials discovery. Large databases such as the Materials Project, AFLOW, and OQMD host computationally derived properties of hundreds of thousands of compounds. Researchers now apply machine‑learning models—graph neural networks, random forests, gradient‑boosted trees—to predict:

- Likelihood of superconductivity given composition and structure

- Estimated \(T_c\) ranges

- Stability windows under pressure and temperature

- Key descriptors like electron–phonon coupling constants and density of states at the Fermi level

A typical workflow might look like this:

- Train models on known superconductors and non‑superconductors.

- Screen millions of hypothetical compounds in silico.

- Down‑select to a few dozen promising candidates for synthesis.

- Use high‑throughput experimental platforms—robotic deposition, rapid annealing, and automated characterization—to test candidates.

- Feed the new data back into the model for iterative improvement.

This approach does not eliminate the need for deep physical insight; instead, it prioritizes which regions of the vast “materials genome” are worth an expensive experimental shot.

Scientific Significance: Beyond Hype and Headlines

The LK‑99 and hydride controversies highlighted a structural tension in modern science:

- The genuine possibility of transformative breakthroughs

- Publication and career incentives that reward dramatic claims

- The amplification power of social media and preprint servers

- The difficulty of reproducing complex, delicate experiments

Yet the long‑term scientific impact has been largely positive. The field has become a live case study in:

- Reproducibility: Independent replication, blind analysis, and standardized reporting checklists are gaining traction.

- Open science: More groups share raw transport and magnetization data, analysis scripts, and detailed synthesis protocols.

- Statistical rigor: Better handling of background subtraction, noise, contact resistance, and systematic errors.

“Extraordinary claims demand not just extraordinary evidence, but also extraordinary transparency.” — A recurring theme in commentary by condensed‑matter theorists and experimentalists.

Importantly, “near‑room‑temperature” under high pressure remains a vibrant area of serious research: multiple hydride systems with \(T_c\) above 200 K are widely regarded as robust under stringent scrutiny. They serve as a roadmap for how to systematically raise \(T_c\) and potentially relax the pressure requirements over time.

Milestones: From Early Superconductors to the 2025 Reboot

Historic Milestones

- 1911: Kamerlingh Onnes discovers superconductivity in mercury at 4.2 K.

- 1957: BCS theory provides the first microscopic explanation of superconductivity.

- 1986–1987: Bednorz and Müller discover cuprate high‑\(T_c\) superconductors, quickly pushing \(T_c\) above 90 K.

- 2001: MgB\(_2\) with \(T_c \approx 39\) K shows that relatively simple compounds can have high \(T_c\).

- 2015–2019: H\(_3\)S and LaH\(_{10}\) hydrides reach >200 K \(T_c\) under megabar pressures.

Recent Milestones and Course Corrections (2020–2025)

- Early hydride claims scrutinized: Re‑analyses and replication efforts fail to confirm some of the most spectacular results, culminating in retractions.

- LK‑99 viral wave (2023): Global labs, from professional facilities to hobbyist garages, attempt replication. Within weeks, consensus emerges that LK‑99 is not superconducting.

- Standardization push (2024–2025): Journals and large collaborations introduce recommended protocols and reporting standards for superconductivity claims.

- ML‑guided discovery ramps up: Several 2024–2025 preprints showcase successful prediction‑and‑verification cycles for unconventional superconductors at intermediate \(T_c\).

These milestones show a field that is self‑correcting, increasingly data‑driven, and open to revising cherished narratives when the evidence demands it.

Challenges: Why Room‑Temperature, Ambient‑Pressure Superconductors Are Hard

Fundamental Physics Challenges

- Pairing mechanisms: Conventional electron–phonon pairing has intrinsic limits; unconventional mechanisms (spin fluctuations, orbital currents, etc.) are less well understood and harder to engineer.

- Competing phases: In strongly correlated systems, superconductivity competes with magnetism, charge order, and structural instabilities.

- Quantum criticality: Some of the highest \(T_c\) materials sit near quantum critical points; tuning to these regimes without causing disorder or instability is delicate.

Experimental and Engineering Challenges

- Extreme pressures: Diamond anvil cells reach >300 GPa but handle tiny sample volumes; scaling such conditions to real devices is non‑trivial.

- Sample quality: Minute variations in stoichiometry, grain boundaries, and defects can make or break superconductivity.

- Measurement artifacts: Poor contacts, inhomogeneous current paths, flux trapping, and proximity effects can mimic or mask superconducting signatures.

- Scalability: Even if a material works in thin films or micro‑crystals, producing kilometer‑scale wires or large‑area tapes is an entirely different challenge.

Social and Epistemic Challenges

- Balancing open, rapid preprint dissemination with careful vetting of extraordinary claims.

- Avoiding “hype cycles” that disillusion the public and funders.

- Ensuring that null results and replication failures are visible and valued.

“It’s not that room‑temperature superconductivity is impossible; it’s that nature is under no obligation to make it cheap or easy for us.” — Paraphrasing comments from multiple theorists in public lectures and YouTube explainers.

Potential Applications and Practical Timelines

Even without a perfect room‑temperature, ambient‑pressure superconductor, incremental progress is valuable. Materials that superconduct at, say, 50–100 K with good critical fields and currents already enable:

- High‑field NMR and MRI systems using REBCO coated conductors

- Compact fusion magnets (e.g., in designs similar to MIT’s SPARC)

- Improved wind‑turbine generators and grid components

For engineers and advanced hobbyists, there is now an ecosystem of hardware that makes working with existing superconductors more accessible. For example, a high‑quality cryogenic vacuum dewar or compact cryocooler can drastically lower the barrier to entry for low‑temperature experiments, and precision multimeters and low‑noise current sources are essential for transport measurements.

As one concrete example, many low‑temperature labs use precision benchtop multimeters such as the Keysight 34461A Truevolt digital multimeter for high‑accuracy resistance and voltage measurements in superconducting transport experiments.

Timelines for truly room‑temperature, ambient‑pressure superconductors remain speculative. Many experts consider a robust discovery within the next few decades plausible but far from guaranteed. What is more certain is that the techniques, infrastructure, and understanding built along the way will continue to spill over into related fields—from quantum devices and spintronics to energy storage and advanced magnets.

Science Communication, Social Media, and the LK‑99 Effect

The LK‑99 episode is now a staple topic in science‑communication talks and media literacy courses. It demonstrated both the power and the pitfalls of a world where:

- Preprints on arXiv can reach millions overnight.

- YouTube creators such as Sabine Hossenfelder and Veritasium quickly analyze and explain new claims.

- Physicists live‑tweet replication attempts and discuss data in near‑real time on X/Twitter and Mastodon.

On the positive side, the public watched scientific self‑correction unfold almost live: as magnetization curves, transport plots, and micrographs appeared, experts annotated them, questioned assumptions, and refined interpretations.

On the negative side, the cycle amplified premature certainty and sometimes blurred the line between speculation and confirmation. Many creators now use LK‑99—along with earlier high‑pressure hydride controversies—as case studies in:

- How to distinguish hypothesis, preliminary evidence, and robust confirmation.

- Why replication and independent verification matter.

- How incentives and attention can distort the scientific process if left unchecked.

Conclusion: A More Mature Era for Room‑Temperature Superconductivity

As of late 2025, room‑temperature (and near‑room‑temperature) superconductivity is neither a solved problem nor a fantasy. It is a frontier under intense, increasingly rigorous exploration. The hydride retractions and LK‑99 non‑replication have:

- Raised experimental and statistical standards

- Accelerated the adoption of open data and reproducibility practices

- Pushed theorists and experimentalists toward closer collaboration

- Shaped a more scientifically literate public conversation about “how science works”

Whether or not a practical room‑temperature, ambient‑pressure superconductor emerges soon, the journey itself is reshaping condensed‑matter physics. Every carefully documented failure to reproduce, every incremental increase in \(T_c\), and every new insight into electron correlation and lattice dynamics helps refine our map of the quantum materials landscape.

The reboot, in short, is less about salvaging a dream than about rebuilding trust—trust between labs, between theory and experiment, and between science and the wider public eager for the next transformative technology.

Further Reading, Tools, and How to Follow the Field

How to Stay Updated

- Monitor the cond‑mat.supr‑con stream on arXiv for the latest preprints.

- Follow experts such as Ranga Dias (for context on hydride debates), Patrick Lee, and other condensed‑matter theorists on professional platforms like LinkedIn and institutional pages.

- Watch critical explainers on YouTube channels including Physics Girl, DrPhysicsA, and university‑run outreach channels.

Technical References and Reviews

- Comprehensive reviews on hydride superconductors in journals such as Reviews of Modern Physics and Nature Reviews Materials.

- Methodological white papers on best practices for superconductivity claims, often posted as open‑access preprints or journal guidelines.

- Open datasets and tools from materials‑informatics platforms like the Materials Project.

For students and professionals entering the field, a solid grounding in solid‑state physics, quantum mechanics, and numerical methods is essential. Standard textbooks on superconductivity, supplemented by recent review articles and online lecture series, provide the conceptual foundation needed to critically evaluate future claims—whether trumpeted on social media or quietly reported in specialized journals.

References / Sources

- Nature – Superconductivity collection

- Science Magazine – Superconductivity topic

- arXiv – Superconductivity (cond‑mat.supr‑con)

- The Materials Project – Materials database

- Nature news on LK‑99 and ambient superconductivity claims

- Nature commentary on reproducibility in superconductivity

- Reviews of Modern Physics – Review on hydride superconductivity