JWST vs. the ‘Too‑Early’ Universe: What High‑Redshift Galaxies Really Mean for Cosmology

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is giving astronomers their sharpest look yet at the infant cosmos, revealing galaxies at redshifts z > 10 that appear startlingly bright, massive, and well‑organized. These discoveries have fueled the viral “too‑early universe” narrative—claims that such galaxies formed so quickly that standard cosmology must be wrong. In reality, JWST’s high‑redshift galaxies are forcing a recalibration of galaxy‑formation models, not a rejection of the Big Bang or ΛCDM (Lambda Cold Dark Matter). Understanding why requires looking carefully at the data, the methods, and the physics behind the headlines.

Below, we explore JWST’s mission and instruments, how these high‑redshift galaxies are found and weighed, why some early interpretations were revised, and what the emerging picture means for dark matter, star formation, and the epoch of reionization.

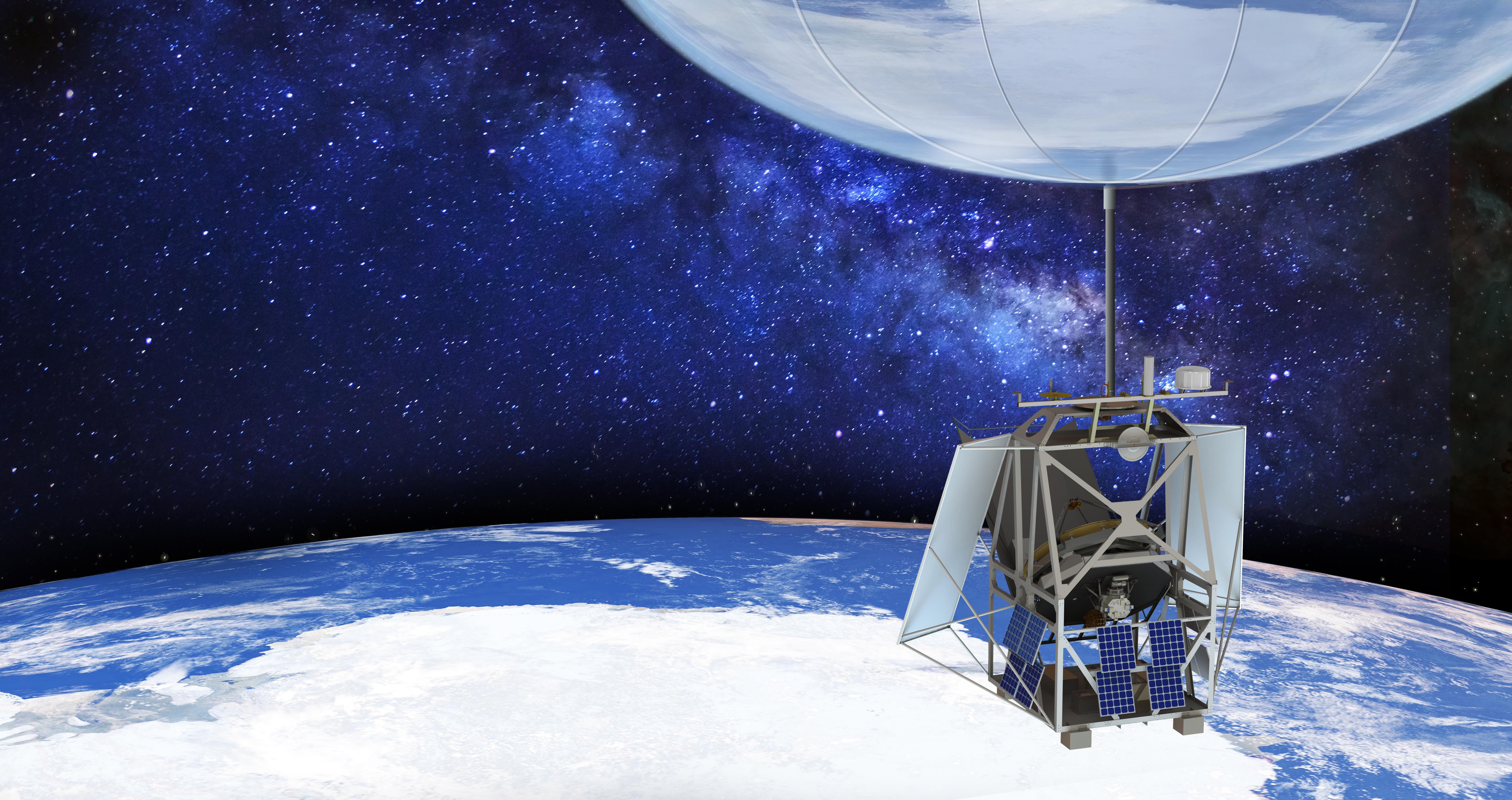

Mission Overview: JWST and the High‑Redshift Frontier

JWST was launched in December 2021 as the scientific successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, optimized for infrared observations. By observing in the near‑ and mid‑infrared, JWST can see light from the earliest galaxies whose ultraviolet and visible emissions have been stretched by cosmic expansion into longer wavelengths.

The “high‑redshift galaxy revolution” primarily comes from JWST’s early deep surveys, such as:

- CEERS (Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science Survey)

- JADES (JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey)

- GLASS‑JWST (Grism Lens‑Amplified Survey from Space)

- PRIMER (Public Release IMaging for Extragalactic Research)

These programs target tiny patches of sky for extremely long exposures, building up deep “time‑machine” images that sample billions of years of cosmic history.

“Webb is pushing our view of the universe back to less than 3% of its current age. We’re not rewriting the Big Bang; we’re learning how surprisingly quickly structure can assemble within that framework.” — Dr. Andrew J. Bunker, JADES collaboration

Online, these images circulate widely on platforms like X (Twitter), Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube, often with commentary that ranges from carefully accurate to wildly speculative. The scientific reality lies somewhere between the two extremes of “nothing new” and “cosmology is dead.”

Technology: How JWST Finds and Probes High‑Redshift Galaxies

JWST’s power for early‑universe studies comes from a combination of large aperture (6.5 m), cryogenic optics, and highly sensitive infrared instruments. Three are central to the high‑redshift galaxy story:

NIRCam: The High‑Redshift Galaxy Finder

The Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam) is JWST’s workhorse imager. It uses multiple filters spanning roughly 0.6–5 μm to detect:

- The Lyman break—a sharp drop in flux caused by hydrogen absorption, used to estimate redshifts photometrically.

- Rest‑frame ultraviolet continuum, tracing young, massive stars and star‑formation rates.

- Rest‑frame optical light (for z > 6), offering clues about older stellar populations and stellar mass.

NIRSpec: Spectroscopic Reality Check

The Near Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) disperses light into spectra, providing accurate:

- Spectroscopic redshifts via emission lines like Lyman‑α, [O III], H‑β, and H‑α.

- Metallicities, ionization conditions, and gas kinematics.

- More reliable constraints on stellar populations and star‑formation histories.

Early viral claims about “impossibly massive” galaxies often relied on photometric redshifts. NIRSpec follow‑up has, in several cases, revised galaxy distances downward or adjusted their inferred masses, illustrating how provisional initial estimates can be.

MIRI and the Dusty Early Universe

The Mid‑Infrared Instrument (MIRI) extends coverage to 28 μm. For high‑redshift studies, MIRI:

- Traces warm dust heated by intense star formation or active galactic nuclei (AGN).

- Helps separate starburst galaxies from AGN‑dominated systems.

- Constrains total infrared luminosities and more complete star‑formation rates.

For readers interested in technical specifications and mission design, NASA’s official JWST site provides detailed instrument handbooks, while preprint servers like arXiv.org host up‑to‑date survey papers.

The ‘Too‑Early’ Universe Debate: What’s Actually in Tension?

Early JWST papers and preprints reported candidate galaxies at redshifts z ≈ 10–16 with inferred stellar masses up to ~10¹⁰–10¹¹ M⊙ and surprisingly high UV brightness. Headlines quickly amplified these results into claims that the Big Bang or ΛCDM paradigm was in crisis.

Standard Expectations from ΛCDM

The ΛCDM model—with cold dark matter, dark energy, and nearly scale‑invariant primordial fluctuations—predicts that:

- Small dark‑matter halos collapse first, merging hierarchically into larger systems.

- Gas falls into halos, cools, and forms stars at rates regulated by feedback from supernovae and black holes.

- Massive, well‑settled galaxies become common only after several hundred million years.

Within this framework, some massive galaxies at z > 10 are allowed, but they are expected to be rare. The “too‑early” concern arises when inferred number densities and stellar masses appear higher than predicted.

“There is tension, but it is primarily about the efficiency of turning baryons into stars in the earliest halos. ΛCDM is not yet in existential danger.” — Paraphrasing commentary from several cosmologists in Nature news features

Key Places the Tension Can Arise

Current discussion focuses on whether we have:

- Overestimated stellar masses due to template choices, dust assumptions, or contributions from emission lines.

- Misestimated redshifts for some photometric candidates, mixing moderately distant dusty galaxies with truly high‑z systems.

- Underestimated star‑formation efficiency in the first halos, which might be much higher than at later times.

- Incomplete feedback models, where outflows from supernovae or AGN might be less effective in shallow early potential wells than in many simulations.

The consensus emerging by late 2024–2025 is that the Big Bang model remains intact, while galaxy‑formation physics—especially the balance between gas inflow, cooling, star formation, and feedback—probably needs adjustments at very high redshift.

Mission Overview: Surveys, Catalogs, and Data Pipelines

JWST’s high‑redshift discoveries are not one‑off anomalies; they come from systematically designed surveys that provide statistically meaningful galaxy samples. A simplified pipeline looks like this:

- Deep imaging with NIRCam across multiple filters.

- Source extraction to identify candidate galaxies and measure photometry.

- Photometric redshift fitting using spectral energy distribution (SED) models.

- Selection of high‑z candidates based on best‑fit redshifts and dropout criteria.

- Follow‑up spectroscopy with NIRSpec and other facilities (e.g., ALMA) for a subset.

- Model comparison with cosmological simulations and semi‑analytic models.

Public data releases from programs like JADES and CEERS allow independent teams to cross‑check catalogs and methods, which has led to both confirmation and revision of early high‑mass claims.

Many of the relevant preprints are discussed on platforms like X (Twitter) by astronomers and on YouTube channels such as PBS Space Time, which frequently explores implications of JWST data in an accessible but technically informed way.

Technology and Methodology: Measuring Masses at the Edge of Time

The claim that some galaxies are “too massive too early” hinges on how we estimate stellar masses and star‑formation rates from observations. This is non‑trivial even for nearby galaxies and becomes more uncertain at z > 10.

Stellar Mass Estimation

Stellar masses are typically inferred by fitting observed photometry with stellar population synthesis models, which depend on:

- The assumed initial mass function (IMF).

- The star‑formation history (burst vs. continuous).

- Metallicity and dust attenuation.

- Nebular emission line contributions to broadband flux.

If the early universe has:

- A more top‑heavy IMF (more massive stars relative to low‑mass stars),

- Different dust properties, or

- Strong emission lines boosting apparent continuum flux,

then “standard” mass conversions can overestimate masses, sometimes by factors of several.

Star‑Formation Rates and Efficiency

Star‑formation rates (SFRs) are inferred from UV and IR luminosities, but converting light to SFR depends on:

- The lifetimes of massive stars dominating UV output.

- Dust obscuration and reprocessing of UV into IR.

- AGN contamination in some systems.

To evaluate whether galaxies are “too efficient,” researchers compare observed stellar mass densities and SFR densities with predictions from simulations such as IllustrisTNG and EAGLE.

“Current simulations generally underpredict the stellar mass in galaxies at z > 10, but the discrepancy is sensitive to assumptions about feedback and star‑formation thresholds.” — Summary of themes from multiple JWST comparison papers on arXiv

Scientific Significance: What High‑Redshift Galaxies Tell Us

Rather than breaking cosmology, JWST’s high‑redshift galaxies are sharpening our understanding of multiple key epochs and processes in cosmic history.

1. The Epoch of Reionization

Between roughly 400 million and 1 billion years after the Big Bang, the first luminous sources ionized the neutral hydrogen permeating the universe. Bright, compact galaxies seen by JWST are prime candidates for driving this process.

Important questions include:

- What fraction of ionizing photons escape from galaxies into the intergalactic medium?

- How clumpy is the gas, and how does that affect reionization topology?

- Do faint, numerous galaxies or relatively rare, luminous ones dominate the photon budget?

2. Early Supermassive Black Holes

JWST is finding both star‑forming galaxies and active galactic nuclei at high redshift. Understanding how black holes grew to >10⁸–10⁹ M⊙ by z ≈ 6–7 is an active area of research.

Possibilities include:

- Rapid growth from stellar‑mass “seed” black holes.

- Direct collapse of massive gas clouds into black holes of 10⁴–10⁵ M⊙.

- Episodes of super‑Eddington accretion.

3. Feedback and Baryon Cycling

The balance between gas inflows, star formation, and outflows is encoded in galaxy scaling relations. Early data suggest that:

- Star‑formation efficiencies may be higher in the first halos than previously modeled.

- Feedback might be less effective at expelling gas, at least in some mass ranges.

This has knock‑on effects for metallicity evolution, the build‑up of the stellar mass function, and the structure of the circumgalactic and intergalactic medium.

Milestones: Key JWST Discoveries Powering the Debate

Since JWST’s first light, several landmark results have driven the “too‑early” universe discussion. A few illustrative milestones include:

- Early CEERS and GLASS results (2022–2023): Identification of photometric candidates at z ≳ 13–16 with unexpectedly high luminosities, quickly turning into viral stories about “the impossible universe.”

- JADES spectroscopic confirmations: Secure redshifts for galaxies at z > 10–13, confirming that such early systems are not rare curiosities, though some extreme mass estimates were revised.

- Refinements to stellar mass estimates: Papers incorporating updated SED models, nebular emission, and more flexible star‑formation histories significantly reduced inferred stellar masses for some objects.

- First detailed metallicity and ionization measurements: Spectra showing surprisingly enriched gas and extreme ionization conditions, pointing to very rapid early chemical evolution.

Collectively, these milestones have moved the discussion from shock to synthesis: from “are these real?” to “what do they teach us about early structure formation?”.

Challenges: Uncertainties, Systematics, and Model Limitations

Interpreting JWST’s high‑redshift universe is challenging on multiple fronts. Recognizing these limitations is crucial for separating hype from genuine theoretical stress tests.

Observational Challenges

- Photometric vs. spectroscopic redshifts: Many candidates still lack spectroscopic confirmation, leaving room for interlopers.

- Cosmic variance: Deep fields probe tiny sky areas; a few overdense regions can bias impressions of typical galaxy populations.

- Lens modeling: For galaxies behind clusters, magnification uncertainties propagate directly into luminosity and mass estimates.

Theoretical and Modeling Challenges

- Sub‑grid physics: Large cosmological simulations cannot resolve individual stars or small molecular clouds, so star formation and feedback are modeled with prescriptions that may break down at extreme redshifts.

- IMF assumptions: A top‑heavy IMF could produce more light per unit mass, altering mass estimates and the energy budget.

- Dark‑matter microphysics: While ΛCDM works well on large scales, small‑scale behavior (e.g., warm dark matter, self‑interactions) remains poorly constrained.

“It’s not that JWST is falsifying cosmology; it’s that it’s telling us we don’t yet understand how efficient the universe can be at making stars in its first few hundred million years.” — Dr. Becky Smethurst, astrophysicist and science communicator

Public Discourse: Social Media, Hype, and Scientific Literacy

The “too‑early” universe debate has exploded far beyond academic journals. Threads on X, TikTok explainers, and YouTube documentary‑style videos now shape public perception of cosmology as much as formal press releases.

Common patterns include:

- Sensational framings (“JWST disproves the Big Bang”) that misrepresent the nature of scientific tension.

- Constructive explainers from scientists who unpack the data and models in accessible language.

- Healthy skepticism as early preprints are revised, demonstrating the self‑correcting nature of science.

For thoughtful commentary, accounts such as Ethan Siegel and Katie Mack regularly discuss cosmology news, including JWST results, providing a bridge between technical literature and public discourse.

Recommended Resources and Tools for Enthusiasts

If you want to dive deeper into JWST’s high‑redshift results or try simple analyses yourself, there are several accessible tools and resources.

Books and Popular‑Level Overviews

- The End of Everything (Astrophysically Speaking) – Katie Mack — Not JWST‑specific, but an excellent primer on cosmology and how we test models.

- Universe Today’s Ultimate Guide to Viewing the Cosmos — For readers inspired to start observing the sky themselves.

Online Data and Visualization

- Webb Telescope Image Gallery — High‑quality, public JWST images with descriptive captions.

- MAST Portal — Access JWST, Hubble, and other mission data directly (for advanced users).

- STScI JWST Calibration Pipeline on GitHub — For technically inclined readers interested in the data‑reduction software.

Conclusion: A Sharper, Not Broken, Cosmos

JWST’s view of the high‑redshift universe is undeniably surprising. Bright, compact galaxies populate the first few hundred million years more abundantly than many pre‑JWST models predicted. But this surprise is driving refinement, not collapse, of cosmological theory.

The Big Bang framework and ΛCDM continue to match the cosmic microwave background, large‑scale structure, and many other datasets. The tension lies in the messy, exciting details of how gas turns into stars and galaxies under extreme conditions—details that were always the least constrained part of the story.

Over the next few years, as more spectroscopic redshifts are secured and simulations catch up with JWST’s discoveries, we can expect:

- Sharper constraints on star‑formation efficiency at early times.

- Improved modeling of feedback and baryon cycling.

- Better understanding of the first black holes and the timeline of reionization.

Far from “breaking cosmology,” JWST is doing what great observatories always do: revealing that the universe is more creative, efficient, and interesting than our first models assumed—and challenging us to catch up.

Additional Perspective: How to Critically Read “Cosmology Is Broken” Headlines

As JWST continues to produce striking results, dramatic headlines will likely continue as well. A few questions can help you evaluate future claims:

- Is the result based on photometric or spectroscopic redshifts? Spectroscopic confirmation greatly strengthens the case.

- How large is the sample? A single outlier is more likely to reveal an unusual object or systematic than to overthrow a theory.

- What assumptions went into mass and SFR estimates? Look for discussions of IMF, dust, and emission‑line contributions.

- What do multiple independent teams say? Robust tensions usually persist across methods and groups.

Following these simple checks not only improves scientific literacy, it also makes the unfolding JWST story more enjoyable—because you can appreciate both the genuine surprises and the healthy skepticism that defines good science.

References / Sources

Selected references and resources for further reading:

- JWST Official Site (NASA/ESA/CSA)

- Nature: James Webb Space Telescope Collection

- JADES: Discovery and properties of some of the earliest galaxies (arXiv)

- Early CEERS results on high‑redshift galaxy candidates (arXiv)

- NASA: JWST Latest Observations and News

- PBS Space Time: What JWST Is Telling Us About the Early Universe (YouTube)