James Webb Space Telescope: Too‑Early Galaxies, Alien Atmospheres, and a New Cosmic Puzzle

Launched in December 2021 and delivering its first science images in mid‑2022, the James Webb Space Telescope is now the flagship observatory for infrared astronomy. By 2025, JWST has produced a torrent of high‑impact discoveries: galaxies shining just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, unprecedented maps of exoplanet atmospheres, and deep insights into cosmic reionization and galaxy evolution.

Its capabilities—anchored by a 6.5‑meter segmented mirror, ultra‑cold instruments at the Sun–Earth L2 point, and cutting‑edge infrared detectors—allow astronomers to peer further back in time and probe fainter structures than ever before. These data have triggered intense scientific debate and have become a cultural phenomenon across social media, YouTube, podcasts, and news outlets.

Mission Overview

JWST is a joint mission of NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA). Operating around 1.5 million kilometers from Earth, it observes the universe primarily in the near‑infrared (NIR) and mid‑infrared (MIR), wavelengths that are crucial for:

- Detecting redshifted light from the earliest galaxies.

- Probing the cool dust and gas where stars and planets form.

- Analyzing the chemical fingerprints in exoplanet atmospheres.

JWST’s key science goals are often summarized in four themes:

- First Light and Reionization – Identifying and characterizing the earliest galaxies and stars that ended the cosmic dark ages.

- Assembly of Galaxies – Tracing how galaxies grow, merge, and chemically evolve across cosmic time.

- Birth of Stars and Protoplanetary Systems – Studying stellar nurseries and young planetary systems embedded in dust.

- Planetary Systems and the Origins of Life – Measuring atmospheres of exoplanets and small bodies in our own Solar System to constrain habitability.

“Webb was built to answer questions we did not yet know how to ask.”

Technology: How JWST Sees the Early Universe

JWST’s transformational discoveries arise from a carefully integrated suite of technologies. Understanding these tools helps explain why it is uniquely sensitive to early galaxies and exoplanet atmospheres.

Segmented Mirror and Optics

JWST’s 18 hexagonal beryllium mirror segments form a 6.5‑meter primary mirror—over six times the collecting area of Hubble’s. Each segment is coated in gold to maximize reflectivity in the infrared. Micron‑precision actuators align the segments into a single optical surface, a process called wavefront sensing and control.

- Large aperture: Collects more photons, enabling detection of extremely faint, high‑redshift galaxies.

- Diffraction‑limited performance: Sharp images at wavelengths ≥ 2 microns for accurate morphology and structural measurements.

Cryogenic Cooling and Sunshield

Infrared astronomy demands cold optics. JWST uses a five‑layer Kapton sunshield roughly the size of a tennis court to block sunlight and Earthshine, passively cooling the telescope to about 40 K (−233 °C). The Mid‑Infrared Instrument (MIRI) is cooled even further, to around 7 K, using a cryocooler.

- Reduces thermal noise that would otherwise swamp faint cosmic signals.

- Permits sensitive observations in the mid‑infrared, particularly important for dust and molecules.

Key Science Instruments

JWST’s main instruments and their roles in the “too‑early galaxy” and exoplanet stories include:

- NIRCam (Near‑Infrared Camera): Primary imaging instrument. Its deep, multi‑filter surveys (e.g., CEERS, JADES) are the source of many candidate high‑redshift galaxies.

- NIRSpec (Near‑Infrared Spectrograph): Provides spectroscopy, including multi‑object spectroscopy with micro‑shutter arrays—critical for confirming galaxy redshifts and measuring emission lines.

- NIRISS: Offers slitless spectroscopy and aperture‑masking interferometry, useful for exoplanet transit studies and high‑contrast imaging.

- MIRI (Mid‑Infrared Instrument): Extends coverage to longer wavelengths, probing dusty galaxies and complex molecules in disks and atmospheres.

The “Too‑Early” Galaxies: What JWST Actually Found

Among JWST’s most contentious discoveries are galaxies apparently existing just 300–500 million years after the Big Bang, at redshifts z ≈ 10–16. Early NIRCam imaging revealed surprisingly bright, compact objects whose colors suggested extremely high redshifts. Some initial mass estimates implied galaxies with stellar masses comparable to today’s Milky Way forming in a fraction of a billion years.

From Candidates to Confirmed High‑Redshift Galaxies

Early surveys such as CEERS (Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science Survey) and JADES (JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey) identified tens of candidates. Follow‑up spectroscopy with NIRSpec and NIRCam slitless modes has:

- Confirmed a growing sample of galaxies at z > 10, with some robustly above z ≈ 13.

- Refined redshift estimates, often lowering initial photometric overestimates but still keeping many objects in the extreme high‑z regime.

- Revised stellar masses downward in some cases due to better modeling of stellar populations and nebular emission.

“We’re not in a crisis, but Webb is telling us the early universe was busier than we expected.”

Galaxy Luminosity Functions and Star‑Formation Rates

JWST has significantly reshaped estimates of the UV luminosity function at high redshift, which describes how many galaxies exist at different brightness levels. The telescope has revealed:

- A higher number density of relatively bright galaxies at z ≳ 8–10 than predicted by many pre‑JWST models.

- Evidence that star‑formation rate density may remain higher out to earlier times than extrapolated from Hubble data.

- Complex, possibly bursty star‑formation histories, with some galaxies showing strong emission lines indicative of massive, young stars.

While many “too‑big” mass estimates have been moderated, the overall picture still suggests a surprisingly rapid buildup of stellar mass and heavy elements in the universe’s first few hundred million years.

Cosmological Implications: Is ΛCDM in Trouble?

The prevailing cosmological model, ΛCDM (Lambda‑Cold Dark Matter), has been remarkably successful in explaining cosmic microwave background (CMB) anisotropies, large‑scale structure, and the expansion history of the universe. The initial JWST claims of “galaxies that shouldn’t exist” raised concerns that ΛCDM might break at early times.

From Headlines to Quantitative Tension

By 2024–2025, the conversation has become more nuanced. Key developments include:

- Improved modeling: Accounting for dust, nebular emission, and complex star‑formation histories often reduces inferred stellar masses.

- Selection effects: Early JWST fields deliberately targeted overdense regions and gravitational lenses, boosting the expected number of bright galaxies.

- Baryonic physics: Star‑formation efficiency, feedback, and the initial mass function (IMF) at early times are still uncertain, leaving room for galaxies to form more efficiently than in some simulations.

Several careful analyses suggest that, while the number of bright, early galaxies is high, it may still be marginally compatible with ΛCDM if one allows for optimistic star‑formation efficiencies and rapid halo growth. However, the tension has sharpened key questions:

- Did the first stars form earlier and more efficiently than expected?

- Is the stellar IMF at high redshift top‑heavy, producing more massive stars?

- Could new physics—such as non‑standard dark matter properties or early dark energy—play a role?

“Webb is not so much killing ΛCDM as stress‑testing every assumption we’ve made about galaxy formation in that framework.”

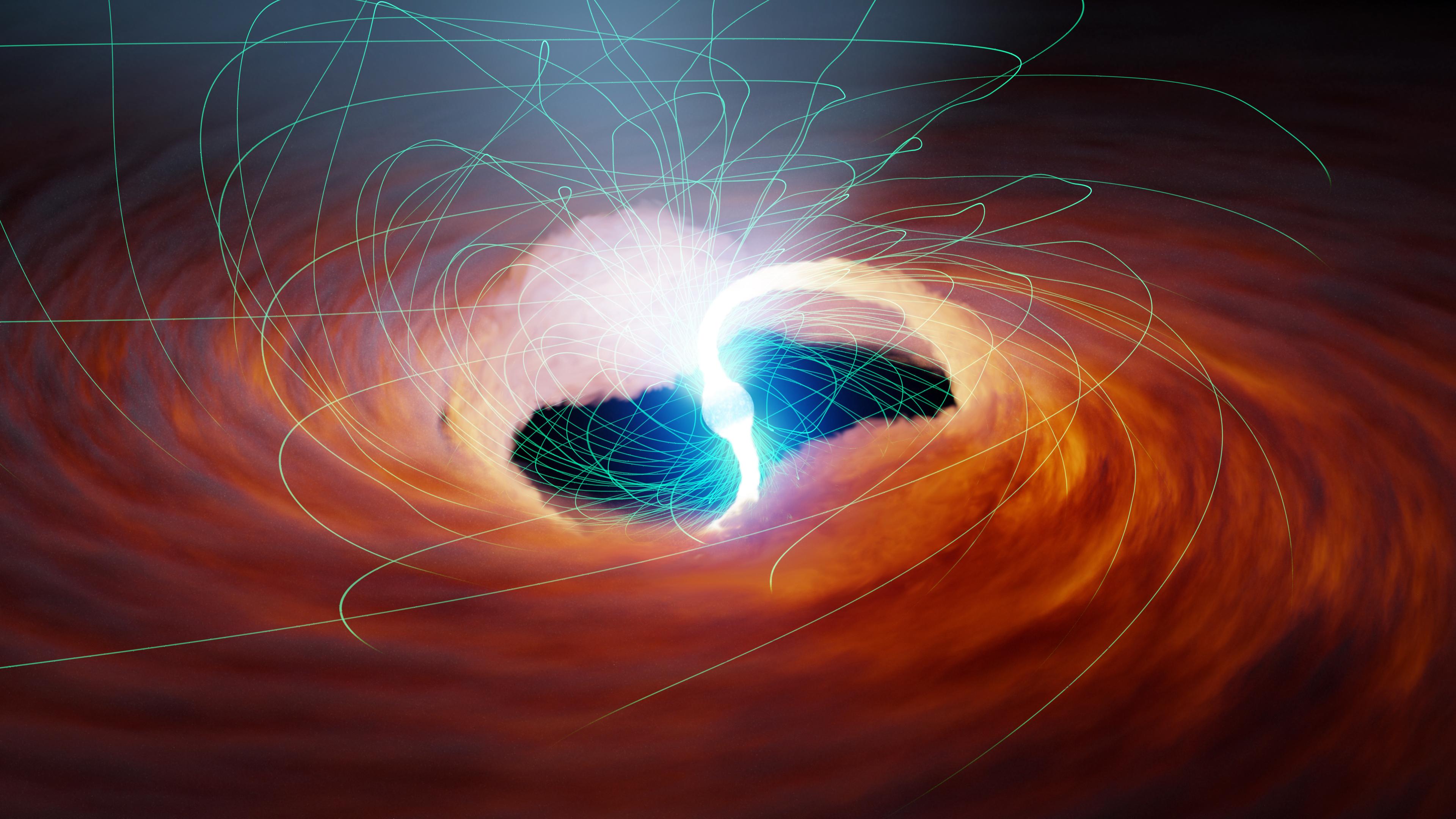

Reionization and the Dawn of Galaxies

One of JWST’s central cosmological roles is to map the process of reionization, the epoch when the first luminous sources ionized neutral hydrogen in the intergalactic medium (IGM). This transition, largely completed by z ≈ 6, sets important constraints on early galaxies and black holes.

Who Reionized the Universe?

JWST observations help address whether reionization was driven predominantly by:

- Numerous faint dwarf galaxies with high escape fractions of ionizing photons.

- A smaller number of bright galaxies and active galactic nuclei (AGN).

- Exotic sources such as Population III (metal‑free) stars or early black holes.

By measuring the abundance, luminosities, and spectral properties of galaxies across 6 ≲ z ≲ 12, JWST is narrowing down the ionizing photon budget. Early results suggest:

- More bright galaxies than expected, contributing significantly to the photon budget.

- Hints of strong nebular emission and very young stellar populations in some early systems.

- Ongoing debate about the role of faint galaxies below JWST’s current detection limit.

Probing the Intergalactic Medium

Spectroscopy of high‑redshift galaxies and quasars can reveal the neutral fraction of hydrogen in the IGM through features like the Lyman‑α line. JWST is helping:

- Map when and where the IGM transitioned from mostly neutral to mostly ionized.

- Test models of patchy, inhomogeneous reionization.

- Connect reionization topology with the large‑scale distribution of galaxies and dark matter halos.

Exoplanet Atmospheres: Reading Alien Skies

Parallel to its work on early galaxies, JWST has rapidly become the premier facility for exoplanet atmospheric spectroscopy. Its instruments can observe transiting exoplanets—planets that pass in front of their star from our viewpoint—and measure how starlight filters through their atmospheres.

Transmission and Emission Spectroscopy

In transmission spectroscopy, JWST records subtle wavelength‑dependent dips during a transit. In emission spectroscopy, it measures the combined light of the star and planet and the change when the planet passes behind the star (secondary eclipse).

These techniques have yielded:

- Clear detections of water vapor (H2O), carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and other molecules in several hot Jupiters and warm Neptunes.

- Evidence of clouds, hazes, and complex vertical temperature structures.

- Early constraints on smaller, rocky or sub‑Neptune planets, including some around the TRAPPIST‑1 system.

“Webb is turning exoplanet atmospheres from cartoons into detailed weather reports.”

Notable Targets and Findings (through 2025)

Some widely discussed JWST exoplanet targets include:

- WASP‑39b: A hot Saturn‑mass planet where JWST detected CO2 with unprecedented clarity, along with evidence for photochemical hazes.

- WASP‑18b and WASP‑121b: Ultra‑hot Jupiters showing strong day‑night temperature contrasts and atmospheric circulation signatures.

- TRAPPIST‑1 planets: Rocky worlds in a compact system; early JWST results have probed their atmospheres (or set upper limits), with ongoing analysis of potential thin atmospheres and surface conditions.

These observations are refining models of atmospheric chemistry, cloud formation, and planet formation pathways—crucial steps toward assessing habitability in future, smaller targets.

Methodology: How Astronomers Decode JWST Data

JWST’s raw images and spectra must pass through a rigorous analysis pipeline before they can challenge cosmological models or characterize exoplanet atmospheres. The process combines sophisticated software, statistical techniques, and physical modeling.

Galaxy Surveys and Modeling

- Photometric selection: Multi‑band NIRCam images are used to identify “dropout” galaxies—objects that disappear in shorter‑wavelength filters due to strong Lyman‑break absorption, indicating high redshift.

- Spectroscopic confirmation: NIRSpec and NIRCam grism data provide precise redshifts by measuring emission lines (e.g., Hα, [O III]) or breaks in the continuum.

- Spectral energy distribution (SED) fitting: Astronomers fit stellar population synthesis models to the observed broadband photometry and spectra to infer stellar mass, age, star‑formation rate, and dust attenuation.

- Simulation comparison: Results are compared with cosmological hydrodynamical simulations (e.g., IllustrisTNG, FIRE, THESAN) run under ΛCDM to assess consistency.

Exoplanet Atmospheric Retrievals

For exoplanets, teams use retrieval codes—Bayesian frameworks that invert observed spectra to infer atmospheric properties. Typical steps include:

- Detrending and systematics correction of JWST time‑series data.

- Fitting transit or eclipse light curves to extract wavelength‑dependent depths.

- Applying radiative‑transfer models with molecular line lists to simulate spectra.

- Using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) or nested sampling to explore parameter space for composition, temperature profiles, and cloud properties.

Public tools and pipelines are increasingly available, enabling cross‑checks between independent groups and broad participation from the global community.

Public Engagement, Open Science, and Learning Tools

JWST’s imagery and discoveries have become a staple of science communication across platforms. Space agencies and independent creators produce explainers, animations, and interactive visualizations that demystify infrared astronomy and cosmology.

Examples of popular, accessible resources include:

- Official NASA/ESA/CSA JWST website with image galleries and education materials.

- YouTube channels like PBS Space Time and Dr. Becky explaining JWST cosmology results.

- NASA’s LinkedIn and other professional networks discussing JWST’s engineering and data‑science challenges.

For readers who want to dive deeper into the science and data analysis, it can be helpful to have supportive technical references at hand. Good entry points include:

- Introductory cosmology textbooks and star atlas combinations.

- Programming and data‑analysis guides geared toward astronomy students.

For example, aspiring data‑driven astronomy students often pair JWST news with hands‑on Python practice using resources like Python in Astronomy: A Guide to Scientific Programming, which walks through real‑world astronomical data workflows similar to those used with JWST.

Key JWST Milestones (2022–2025)

JWST’s journey from deployment to frontier science has been marked by several major milestones, many of which directly involve the “too‑early” galaxies and exoplanet atmospheres.

Selected Timeline

- 2022: First full‑color images and spectra released, including the SMACS 0723 deep field and the Carina Nebula’s “Cosmic Cliffs.”

- 2022–2023: Early Release Science programs (e.g., CEERS, ERS‑01386) identify candidates for extreme high‑redshift galaxies (z > 10).

- 2022–2024: Confirmed detections of CO2 and other molecules in multiple exoplanets; WASP‑39b becomes a benchmark atmospheric target.

- 2023–2025: JADES and other deep surveys refine galaxy luminosity functions and star‑formation histories at z ≳ 8, updating the reionization picture.

- Ongoing (2025+): Time‑domain programs, lensed galaxy studies, and coordinated surveys with ALMA, Hubble, and large ground‑based telescopes build a multi‑wavelength view of the early universe.

Challenges: Uncertainties, Biases, and Instrument Limits

Despite its power, JWST does not provide final answers on its own. Its discoveries come with important caveats that experts must carefully account for.

Observational and Instrumental Challenges

- Photometric uncertainties: At the faintest limits, small calibration errors can significantly affect inferred redshifts and masses.

- Contamination: Lower‑redshift interlopers with strong emission lines or dust reddening can masquerade as high‑z galaxies if not properly modeled.

- Cosmic variance: Deep surveys often cover relatively small sky areas, risking biased sampling of overdense or underdense regions.

- Instrument systematics: Time‑series observations for exoplanets require careful correction of detector systematics and spacecraft trends.

Theoretical and Modeling Challenges

- Stellar population assumptions: Different choices of IMF, stellar tracks, and binary evolution can shift inferred masses and ages.

- Feedback prescriptions: Supernovae, stellar winds, and AGN outflows are complex to model, yet crucial for controlling star‑formation efficiency.

- Non‑equilibrium chemistry: For exoplanets, retrieving atmospheric abundances requires accounting for photochemistry and vertical mixing that drive deviations from simple equilibrium models.

Addressing these challenges requires synergy among observers, theorists, and instrumentation experts, as well as comparison with complementary facilities such as ALMA, Euclid, Vera C. Rubin Observatory, and ground‑based Extremely Large Telescopes (ELTs).

Conclusion: A Busy, Early Universe and a New Era of Precision Cosmology

By 2025, JWST has firmly established that the early universe was more active, more rapidly star‑forming, and chemically richer than many pre‑launch models predicted. The “too‑early” galaxies controversy has shifted from sensational headlines about a broken Big Bang to a more constructive re‑evaluation of galaxy formation physics within (or just beyond) ΛCDM.

At the same time, JWST’s exoplanet results are transforming how we think about planetary atmospheres, climate, and composition across a dizzying variety of worlds. The telescope’s unique combination of sensitivity and spectral coverage makes it the premier facility for both ends of cosmic history—from the first galaxies to potentially habitable exoplanets.

Whether JWST ultimately reveals cracks in our cosmological model or simply forces us to refine our understanding of baryonic physics, it has already achieved something profound: it has made the first billion years of cosmic history and the chemistry of distant worlds empirically accessible, turning long‑standing theoretical speculation into testable science.

Further Reading, Tools, and How You Can Explore JWST Data Yourself

One of JWST’s most exciting aspects is that much of its data is publicly available, enabling students, educators, and enthusiasts to work directly with observations that are reshaping cosmology and exoplanet science.

Explore Real JWST Data

- MAST JWST Archive – Official archive for raw and pipeline‑processed data products.

- STScI JWST Pipeline on GitHub – Software used to calibrate and process JWST observations.

- ESA JWST Science pages – Additional documentation and science highlights.

Educational Resources and Visual Explainations

- NASA Webb First Images – Story maps and deep dives into the earliest JWST releases.

- YouTube: How Webb Sees the Early Universe (NASA Goddard).

- YouTube: Reading Exoplanet Atmospheres with JWST (SciShow Space).

Whether you are a researcher, student, or simply an enthusiast, JWST offers a unique opportunity: for the first time, we can systematically test models of galaxy formation, reionization, and planetary atmospheres using a single, extraordinarily powerful observatory. The story of the “too‑early” galaxies is still unfolding—and you can follow it in real time, directly from the data and the preprints that appear almost daily on arXiv’s astro‑ph section.

References / Sources

Selected reputable sources for deeper study:

- NASA JWST Homepage – https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/webb/main/index.html

- Webb Telescope Science – https://webbtelescope.org/news

- JADES Collaboration Papers (high‑z galaxies with JWST) – https://jades-survey.github.io

- “JWST observations of high-redshift galaxies” (review-style discussions on arXiv) – https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.02463

- WASP‑39b JWST Atmosphere Results – https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-022-05449-w

- TRAPPIST‑1 JWST Observations – https://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/2023/nasa-s-webb-sheds-light-on-trappist-1-planets

- ESA JWST Science & Technology – https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Space_Science/Webb