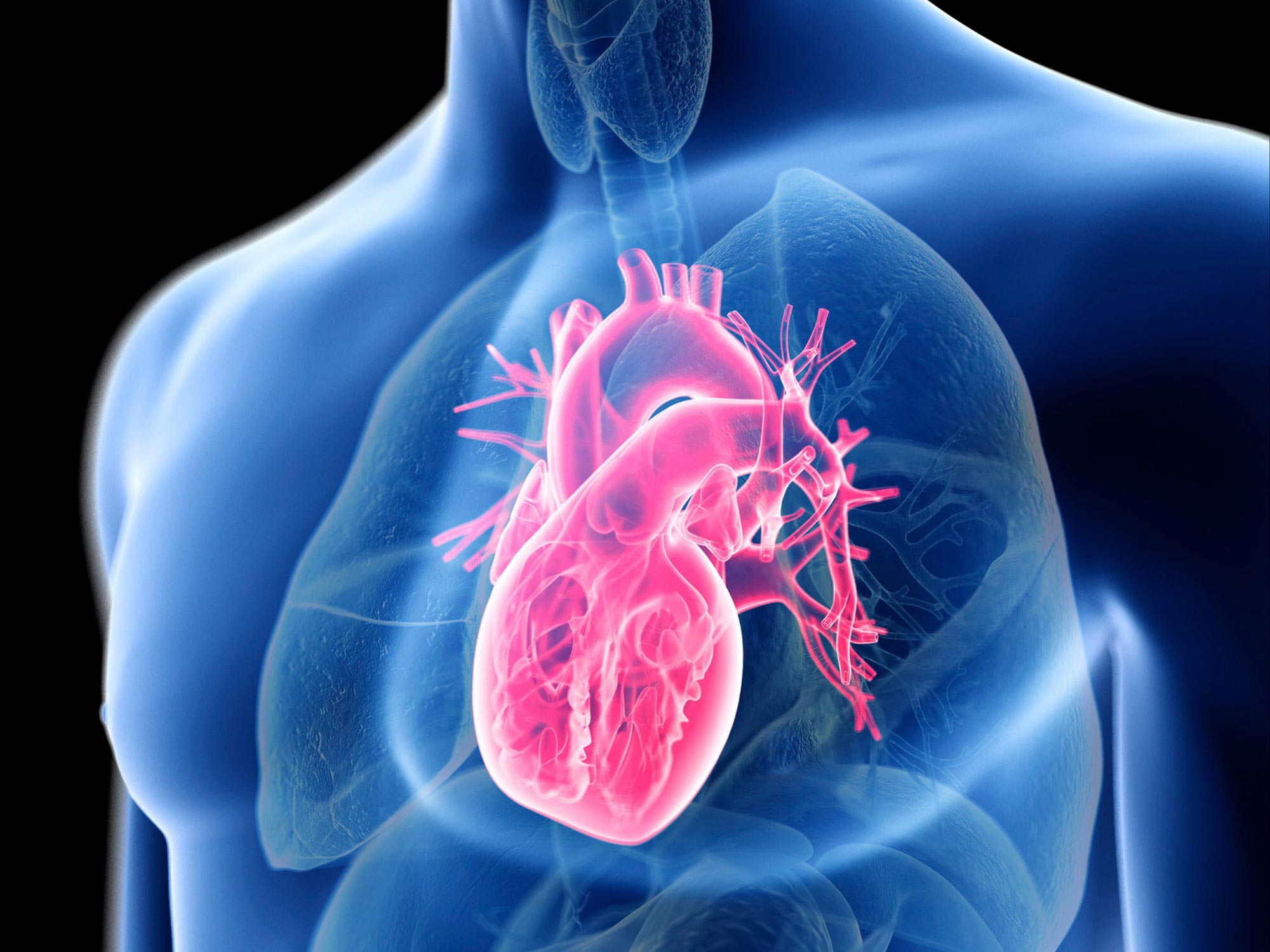

How Regular Exercise Quietly Rewires Your Heart’s Nerves for Lasting Protection

If you’ve ever been told to “exercise for your heart,” you probably pictured your heart muscle getting stronger, like a bicep after weeks in the gym. That image isn’t wrong—but it’s only half the story. New research published in 2024–2025 shows that regular aerobic exercise doesn’t just build heart muscle; it quietly reprograms the nerves that control how your heart works, reshaping your heart’s control system in ways that may protect you from dangerous rhythm problems.

We’ll look at what scientists have discovered, what it means in everyday language, and how you can safely use these insights to support your own heart health—without extreme workouts, fancy trackers, or unrealistic promises.

Why the Heart’s Nerve System Matters More Than We Realized

Your heart isn’t just a pump—it’s part of a finely tuned electrical and nerve network called the cardiac autonomic nervous system. This system balances:

- Sympathetic nerves – the “gas pedal” that speeds up heart rate during stress, exercise, or fear.

- Parasympathetic (vagal) nerves – the “brake” that slows your heart and promotes recovery and calm.

When this balance is off—too much “gas,” not enough “brake”—your risk of problems like atrial fibrillation (AFib), dangerous ventricular arrhythmias, and heart failure rises. For years, doctors have known that exercise improves heart health, but they mostly focused on:

- Stronger heart muscle (better pumping power)

- Cleaner arteries (less plaque, better blood flow)

- Lower blood pressure and improved cholesterol

The new twist from recent studies: moderate, regular exercise actually reshapes how nerves are wired to the heart—and it does so in a side-specific way, with the left and right sides of the heart’s nerve control system adapting differently. This could help explain why some people respond better to certain heart treatments than others.

What the New Research Actually Found (In Plain English)

The SciTechDaily report summarizes recent experimental work showing that regular aerobic exercise remodels the autonomic nerves around the heart. Researchers used advanced mapping tools to study how nerve signals changed with training.

Key findings from this and related research (up to late 2024–2025) include:

- Improved vagal (parasympathetic) tone: Exercise increased the “rest and recover” signals that slow the heart and stabilize its rhythm.

- More controlled sympathetic activity: The “fight or flight” system became more efficient—strong when needed during exercise, calmer at rest.

- Side-specific nerve changes: Nerves on the left and right sides of the heart’s control system adapted differently, which may matter for conditions like AFib and heart failure.

- Better heart rate variability (HRV): The natural beat-to-beat variation in heart rate, a marker of resilient autonomic function, tended to improve with training.

“Regular moderate-intensity aerobic exercise is one of the most effective non-pharmacologic interventions to improve autonomic balance, reduce arrhythmia risk, and enhance overall cardiovascular resilience.”

— Summary of findings from recent American Heart Association scientific statements

While much of this research comes from animal models and highly controlled human studies, the direction is consistent: the heart’s nerve network stays adaptable throughout life, and movement is one of the most powerful tools we have to shape it.

How Exercise “Reprograms” Heart Nerves: The Simple Version

When you move your body, you repeatedly ask your heart to speed up and slow down. Over time, this “practice” doesn’t just strengthen the muscle; it teaches the control system to respond more intelligently.

Here’s a simplified view of what seems to happen with regular moderate exercise:

- During activity: Sympathetic nerves increase heart rate and contractility so you can move, climb, or cycle without running out of steam.

- Immediately after: Parasympathetic (vagal) activity “kicks in” to slow the heart, improve heart rate variability, and promote recovery.

- Over weeks to months: The balance between these systems shifts—your vagal “brake” becomes stronger, and the sympathetic “gas” becomes less jittery and more focused.

- At rest & during stress: Your heart tends to beat more efficiently, stay calmer under everyday stress, and recover faster after exertion.

In some of the newer studies, researchers also found that the left and right sides of the heart’s nerve network change differently with training. That matters because:

- The right side often plays a bigger role in controlling heart rate.

- The left side has more influence on certain arrhythmias and blood pressure control.

Understanding this side-specific adaptation could eventually help doctors fine-tune procedures like cardiac ablation or neuromodulation therapies for AFib and heart failure. For now, the practical takeaway is reassuring: even modest exercise can meaningfully improve how your heart’s control system behaves.

Beyond Muscle: Real-World Benefits of a “Rewired” Heart

When your heart’s nerve control system is better balanced, you don’t necessarily “feel” your nerves changing day to day—but you may notice effects like:

- Lower resting heart rate over time.

- Faster recovery—your heart rate comes down more quickly after exertion.

- Improved heart rate variability (HRV), often seen in fitness trackers as a sign of better resilience.

- Calmer responses to stress—fewer pounding-heart moments in everyday situations.

- Reduced risk markers for arrhythmias and cardiovascular events, especially in people with existing heart disease.

None of this means exercise guarantees you won’t develop heart disease or arrhythmias—genetics, age, and other conditions still matter. But as multiple large studies and guidelines from organizations like the European Society of Cardiology consistently show, physically active people have a lower overall risk of heart events and better quality of life.

A Real-Life Example: From “Out of Breath” to Heart-Confident

Consider a common scenario from cardiac rehab programs: a 62-year-old with high blood pressure and a mild heart attack six months ago. At the start, walking for 5 minutes left them breathless, with a high resting heart rate and poor heart rate recovery after activity.

Under medical supervision, they began:

- Walking on a treadmill 3–4 times per week.

- Starting at 10 minutes and gradually building to 30–40 minutes of moderate effort.

- Adding gentle resistance exercises twice per week.

After 3–4 months:

- Resting heart rate was lower by about 8–10 beats per minute.

- Heart rate recovered more quickly after exercise.

- They reported fewer palpitations and less anxiety about their heart.

We can’t “see” their nerve circuits without specialized tests, but the pattern—lower resting rate, better recovery, improved confidence—is exactly what we would expect if exercise is improving autonomic balance.

“The most powerful changes we see in cardiac rehab aren’t just in the EKG or blood tests—they’re in how patients’ hearts respond to everyday life again.”

— Cardiac rehabilitation nurse (composite anecdote based on typical clinical experiences)

How Much and What Type of Exercise Does Your Heart’s Nerves Need?

Most of the autonomic benefits in research show up with moderate, consistent aerobic activity—not all-out intensity. Current guidelines from the World Health Organization and major cardiology societies generally recommend:

- 150–300 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise (like brisk walking, easy cycling, light jogging, or water aerobics), or

- 75–150 minutes per week of vigorous activity (like running, fast cycling, or uphill hiking), or

- A combination of the two, spread over the week.

For optimal heart and autonomic health, they also recommend:

- Muscle-strengthening activities at least 2 days per week.

- Breaking up long sitting periods with short movement breaks.

If you’re starting from little or no activity, even 10 minutes per day of gentle walking can begin to shift the dial. The key is gradual, sustainable progress.

A 4-Week Gentle Plan to Start Rewiring Your Heart’s Nerves

Here’s a practical, heart-safe template you can adapt. Always adjust based on your doctor’s advice and how you feel.

Weeks 1–2: Build the Habit, Not the Heroics

- Goal: 10–20 minutes of comfortable walking most days.

- Intensity check: You can talk in full sentences, breathing is slightly elevated but manageable.

- Frequency: 4–5 days per week.

Weeks 3–4: Add Gentle Challenge

- Increase to 25–35 minutes per session.

- Add 1–2 short intervals of slightly faster walking for 1–2 minutes, followed by 3–4 minutes easy.

- Include 1–2 light strength sessions (e.g., bodyweight squats to a chair, wall push-ups, light resistance bands).

Over the following months, you can build toward the full 150 minutes per week of moderate activity, or whatever target you and your clinician agree on.

Common Obstacles—and How to Work Around Them Safely

Knowing that exercise can reprogram your heart’s nerves is motivating—but real life is messy. Here are common barriers and evidence-based ways to navigate them.

“I’m afraid of overstraining my heart.”

Fear is understandable, especially after a health scare.

- Start with short, low-intensity sessions and gradually build.

- Use the “talk test”: you should be able to speak, not sing, during exercise.

- If available, ask for a referral to cardiac rehabilitation, which provides supervised, tailored exercise programs.

“I don’t have time.”

- Break movement into 10-minute chunks across the day.

- Walk during phone calls, take the stairs when possible, or park further away.

- Research suggests that even short bouts add up to meaningful benefits over weeks and months.

“I have joint pain or mobility issues.”

- Try low-impact options like cycling, swimming, or water aerobics.

- Consider seated exercises or gentle chair-based cardio.

- Consult a physical therapist for a personalized plan that protects your joints.

Before & After: How Your Heart’s Control System Can Change

These are typical patterns seen in research and clinical practice over several months of consistent, moderate exercise. Individual results vary, and changes can be subtle but meaningful.

Before regular exercise

- Higher resting heart rate.

- Slower recovery after climbing stairs or walking briskly.

- More frequent palpitations or awareness of heartbeat.

- Lower heart rate variability (less flexible control system).

- Greater anxiety about heart sensations.

After months of regular exercise

- Lower resting heart rate.

- Faster heart rate recovery after effort.

- Fewer or less bothersome palpitations (for many people).

- Improved heart rate variability (more adaptive control).

- Increased confidence and reduced fear of activity.

Again, these are trends, not guarantees. Some people need medications, procedures, or devices even with a perfect exercise routine. But moving your body gives your heart’s nerve system a strong advantage.

Quick FAQs About Exercise and Heart Nerve Health

Does high-intensity interval training (HIIT) help too?

HIIT can improve cardiovascular fitness and may enhance autonomic function in some people, but it isn’t necessary to get the nerve-related benefits described here. For those with heart disease or risk factors, moderate, steady activity is usually safer to start with, unless a clinician specifically clears you for HIIT.

Can I overdo exercise and harm my heart?

Very high volumes of intense endurance training over many years may be associated with certain rhythm issues in a minority of athletes, according to some studies. For most people, though, the bigger risk is too little movement, not too much. Staying within guideline ranges and listening to your body is a good safeguard.

How soon will my heart’s nerves start to adapt?

Some autonomic changes—like improved heart rate recovery—can appear within weeks. More stable, long-term remodeling likely requires months to years of consistent activity. Think of it as gradually teaching your heart to respond more wisely, not flipping a switch overnight.

Bringing It All Together: Moving to Support a Smarter Heart

Regular aerobic exercise doesn’t just make your heart stronger—it helps make it smarter by reshaping the nerves that guide every beat. This side-specific, autonomic remodeling is giving scientists new ideas for treating common rhythm problems and gives you a powerful, practical reason to move more.

You don’t need perfect health, a gym membership, or an athlete’s mindset to benefit. What your heart’s nerves seem to respond to best is consistent, moderate movement over time.

If you’re ready to start:

- Talk with your healthcare provider about what’s safe for you.

- Pick one simple activity—like a 10-minute daily walk.

- Schedule it into your day as non-negotiable self-care.

- Increase gradually, listening closely to your body.

Every step you take is not just “burning calories”—it’s sending signals that can help retrain the control system of your heart. That’s a quiet, powerful investment in your future self.