From Hospital Phobia to Helping Births: How Two Women Turned Fear into a Midwife Superpower

Two women who once had crippling hospital phobias now work in maternity care, using their lived experience of fear and trauma to support pregnant people who feel overwhelmed by medical settings and birth. Their journeys from panic to professionalism say a lot about how we treat anxiety, how the NHS talks about trauma, and what genuine compassionate care can look like.

How I Conquered My Hospital Phobia to Become a Midwife

The BBC recently profiled midwife Hope Jezzard and another woman with a similar story: both once avoided hospitals at all costs, and now they actively choose to walk onto wards every day. In an era where birth stories trend on TikTok and medical dramas dominate streaming platforms, their real‑life arcs from nosocomephobia to midwifery read like a character development subplot from a prestige TV series—only this one comes with night shifts, not a writer’s room.

What Is Hospital Phobia (Nosocomephobia), Really?

Hospital phobia, or nosocomephobia, isn’t just “disliking hospitals.” It’s an intense, often overwhelming fear of medical settings—corridors, uniforms, equipment, even the smell of antiseptic—that can trigger panic attacks, avoidance, or dissociation. For some people, it’s rooted in a difficult medical experience in childhood; for others, it’s tied to a fear of loss of control, needles, pain, or bad news.

In the BBC piece, Hope describes reactions so strong that simply entering a hospital felt impossible. That’s the difference between unease and phobia: it’s not a quirk; it’s a barrier to care. When you’re pregnant, that barrier collides with one of the most medically choreographed—and emotionally loaded—experiences of modern life: giving birth.

From Panic at the Door to Calling the Shots on the Ward

Hope’s story, as reported by the BBC, is striking because it flips the usual narrative: instead of avoiding hospitals forever, she moved in closer, training and qualifying as a midwife. The word “inconceivable” gets thrown around in the article—friends and family simply couldn’t imagine her setting foot on a ward, let alone owning the space in a professional uniform.

“My phobia of hospitals was so intense that it seemed inconceivable I would ever work in one. Now, I’m helping women who feel the way I used to.”

— Hope Jezzard, speaking to the BBC

That pivot is important culturally. For decades, medical culture often coded fear as weakness: “good” patients complied, “difficult” patients questioned or avoided. Hope’s journey reframes that completely. Who better to support someone terrified of childbirth than a midwife who once felt her own body lock up at the sight of a ward?

There’s also a generational angle here. Hope is part of a new wave of healthcare professionals who are explicit about mental health, neurodiversity, and trauma histories. Instead of hiding those things in the staff room, they’re increasingly used as tools for empathy and better practice.

Two Women, One Fear: Different Routes to Healing

The BBC article doesn’t just focus on Hope; it also follows another woman whose life was shaped by hospital fear and later turned toward helping others. While the details of their backgrounds differ—family histories, specific triggers, and the path through therapy—they share some key beats:

- A powerful early experience (often in childhood or adolescence) that made hospitals feel unsafe.

- Years of avoidance: skipping check‑ups, panic at the thought of emergency care, dread of pregnancy.

- A turning point—often pregnancy itself or a loved one’s illness—that made avoidance no longer sustainable.

- Structured help: therapy, graded exposure to medical settings, and supportive professionals who didn’t dismiss their fear.

- A decision to “go back” into the system, this time as an insider, to soften the edges for people like them.

What their stories underline is that phobia recovery isn’t linear or neat. It’s not: “cured” on Tuesday, enrolled on the midwifery course by Friday. It’s more back‑and‑forth, full of small exposures—a waiting room here, a blood test there—until one day, the trigger becomes a workplace.

Review: A Quietly Radical BBC Health Story

As a piece of health journalism, “How I conquered my hospital phobia to become a midwife” sits in that sweet spot between human‑interest and service article. It’s not just “inspirational content”; it quietly interrogates how healthcare systems respond when someone is so terrified of the system that they can’t access it.

Structurally, the article does three things well:

- Personal narrative first. By letting Hope and the second woman lead with their experiences, the piece lands emotionally before it starts to educate.

- Accessible explanation of nosocomephobia. It gives enough detail to legitimise the condition without drowning readers in diagnostic jargon.

- Signposting to help. It nods to therapy, midwifery support, and NHS options, which matters for anxious readers who may be mid‑scroll and mid‑panic.

There are, however, limits. While the piece touches lightly on the structural side—how difficult it can be to get psychological support quickly through the NHS—this is mostly an individual success story rather than a systemic critique. Readers don’t get a deep dive into waiting times for therapy, regional inequalities, or the reality that not everyone has the time, money, or support network to do intensive exposure work.

Still, as an entry‑level introduction to hospital phobia in a maternity context, the article is strong: empathetic, practical, and wary of turning trauma into spectacle.

Overall rating: 4/5

Read the full article on BBC News: How I conquered my hospital phobia to become a midwife (search this title on the BBC site for the latest version).

Why This Story Hits Now: Birth, Anxiety and Media Culture

Stories like Hope’s land in a media landscape saturated with medical imagery. On one side, you have hyper‑stylised hospital drama—from Grey’s Anatomy to This Is Going to Hurt—and on the other, an endless scroll of hyper‑real birth clips on Instagram and TikTok. For someone with hospital phobia, that’s not background noise; it’s ambient exposure therapy they never signed up for.

The BBC article subtly pushes back against the idea that bravery looks like stoic silence. Hope doesn’t frame her past fear as an embarrassing weakness to be hidden; instead, it’s a skillset. She uses that history to:

- Spot the early signs of panic in pregnant people entering the ward.

- Advocate for slower, more collaborative care where possible.

- Reassure families that fear of hospitals is common and treatable, not a character flaw.

There’s also a quiet feminist through‑line. Women’s pain and fear in medical contexts—particularly around birth—have a long history of being minimised. By centring two women who refuse to gaslight their own past experiences, the BBC piece contributes to a broader cultural push: believe patients, especially when they tell you they’re scared.

How Do You Actually Overcome a Hospital Phobia?

The women in the article don’t offer a magic fix. Instead, their stories echo what mental health research has been saying for years: specific phobias respond best to gradual, supported exposure and evidence‑based talking therapies.

While individual treatment should always be guided by a professional, the common elements often include:

- Psychoeducation. Understanding what anxiety is doing in your body—racing heart, sweaty palms, tunnel vision—can make it feel less like a personal failing and more like a predictable (treatable) pattern.

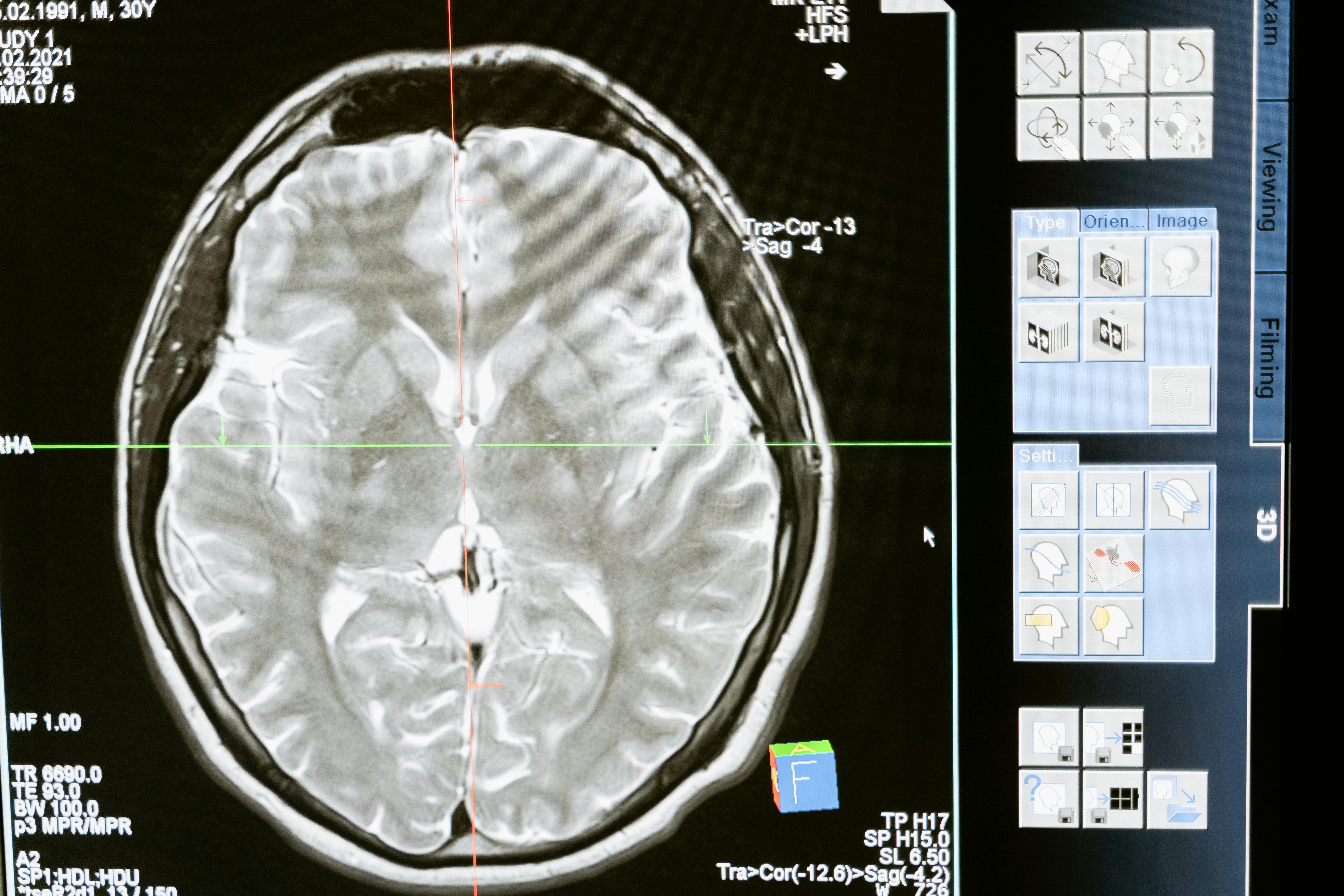

- Graded exposure. Starting far away from the biggest trigger and building up:

- First: talking about hospitals in therapy.

- Next: looking at photos or videos of wards.

- Then: visiting a hospital café or car park with a trusted person.

- Eventually: brief, planned time on a ward.

- Skills training. Breathing exercises, grounding techniques, and practical communication tools (like scripts for telling staff you’re phobic) so you feel less at the mercy of your anxiety.

- Trauma‑informed care. For people whose phobia stems from past medical trauma, therapy may involve processing those experiences, not just “pushing through” them.

Related Viewing and Reading: Birth, Hospitals and Anxiety

If the BBC article left you wanting more depth—or just different perspectives on birth and hospital culture—there’s a growing ecosystem of thoughtful media around these themes.

- TV & Streaming

- Podcasts & Audio

- The Birth Trauma Association Podcast: First‑person stories of difficult births and recovery, including how people renegotiate their relationship with hospitals.

- Mental Health Foundation Podcasts: Episodes on phobias and anxiety that explain the science in plain language.

- Guides

- NHS: Phobias – symptoms and treatment

- Tommy’s: Pregnancy information and support with sections on birth anxiety.

Beyond the Happy Ending: What Stories Like Hope’s Can Change

It would be easy to file the BBC’s piece under “uplifting human‑interest” and move on. But stories like Hope Jezzard’s—and that of the second woman profiled—quietly challenge how we think about both care and courage.

Courage here isn’t not being afraid; it’s walking into the exact space that once paralysed you and saying, “I know how bad this can feel. Let’s make it better.” For pregnant people dreading the hospital, that ’s not just a nice narrative arc—it can be the difference between feeling trapped and feeling accompanied.

Looking ahead, the most interesting question isn’t whether more former phobic patients will become midwives— it’s whether healthcare systems will fully integrate their insights. Trauma‑informed birth plans, flexible environments, and staff who recognise that “difficult” can mean “terrified” are not just nice add‑ons; they are the next logical step in modern, humane maternity care.

Hope’s journey from frozen at the hospital door to calmly guiding births is a reminder that our worst fears don’t have to define us forever. Sometimes, they become the reason we’re exactly the right person for the job.