Frank Gehry’s Shimmering Legacy: How a Rebel Architect Rewired the Skylines of the World

Frank Gehry (1929–2025): The Architect Who Turned Cities into Sculptures

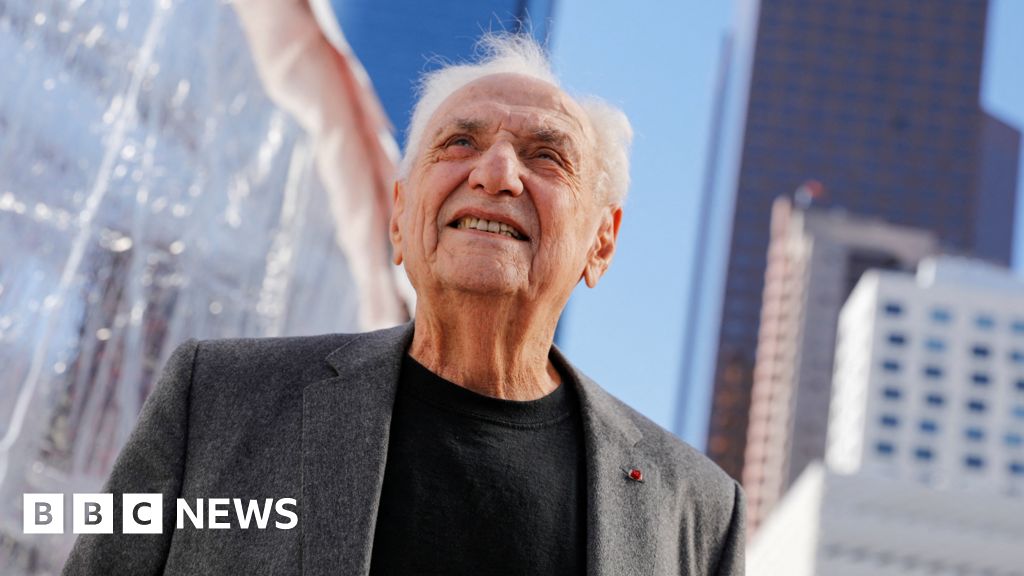

Frank Gehry, the legendary architect behind the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao and Walt Disney Concert Hall, has died at 96, leaving behind a radical body of work that turned buildings into cultural events and reshaped how the world thinks about design. His daring use of industrial materials, fractured forms and sculptural skylines made him one of the defining creative forces of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

News of Gehry’s death has prompted a wave of tributes from architects, artists and cultural institutions worldwide, many of whom owe their own visibility to the so‑called “Bilbao effect” that his work helped create.

From Toronto to Global Icon: A Brief Background on Frank Gehry

Born Frank Goldberg in Toronto in 1929 to a Polish‑Jewish family, Gehry emigrated to Los Angeles as a teenager and eventually studied architecture at USC before a stint at Harvard. The mid‑century Californian landscape—freeways, aerospace labs, and suburban sprawl—became the unlikely incubator for one of architecture’s most restless imaginations.

His early work in the 1960s and 70s flirted with mainstream modernism, but by the late 1970s he had pivoted toward a more provocative, deconstructed language. The turning point was his own house in Santa Monica, where he famously wrapped an ordinary bungalow in corrugated metal and chain‑link fencing, exposing beams and slicing angles in ways that scandalized neighbors and electrified critics.

“I was trying to make the ordinary extraordinary. I didn’t want perfection; I wanted energy.”

The Gehry Look: Jagged Angles, Industrial Materials, and Sculptural Cities

Gehry’s work is instantly recognizable: rippling metal skins, fragmented volumes, and forms that look as if they’ve been frozen mid‑explosion. Where traditional modernism prized clean lines and right angles, Gehry embraced asymmetry and motion, using industrial materials such as titanium and corrugated steel to produce shimmering, almost musical effects.

Yet for all the drama, there was method in the madness. Gehry leaned heavily on physical models—crumpled paper, bent cardboard—before collaborating with engineers and software developers to adapt aerospace design tools like CATIA, allowing his studio to fabricate previously impossible geometries at architectural scale.

The result was a language of architecture that felt as influenced by Cubism and jazz improvisation as by any traditional stylebook. Love it or hate it, you could not mistake a Gehry building for anyone else’s.

The “Bilbao Effect”: How One Museum Changed Urban Culture

When the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao opened in 1997, it wasn’t just a new art museum—it was a global plot twist. The port city of Bilbao, long associated with heavy industry and economic decline, suddenly had a titanium‑clad spaceship sitting on its riverfront. Tourists followed, and so did investment.

Economists and urban planners began talking about the “Bilbao effect”: the idea that an iconic cultural building could reboot a city’s image and economy. Whether that formula is as simple—or as repeatable—as some politicians hope is still up for debate, but Gehry’s role in reframing architecture as a catalyst for cultural tourism is undeniable.

“Bilbao made it clear that a building could be a media event, a branding device, and a piece of serious architecture all at once.”

Walt Disney Concert Hall and the Sound of Steel

If Bilbao made Gehry a superstar, Los Angeles’s Walt Disney Concert Hall (opened in 2003) secured his place in cultural history. The venue is both a civic living room for downtown L.A. and a cathedral of sound, with an interior shaped like a wooden ship and acoustics praised by musicians and critics alike.

Importantly, Disney Hall pushed back against the old idea that serious music belongs in stuffy, neoclassical boxes. Gehry’s swirling forms made classical performance feel contemporary and accessible—Instagrammable before Instagram existed—without turning the building into pure spectacle. For the Los Angeles Philharmonic, it became an architectural avatar for its own progressive, risk‑friendly programming.

Beyond Bilbao: Chairs, Fish, and Digital Frontiers

Though best known for museums and concert halls, Gehry’s influence spilled into product design, interiors, and even virtual realms. His Easy Edges and Experimental Edges furniture series in the 1970s showed how humble cardboard could be transformed into sculptural, durable seating, a kind of early sustainability experiment wrapped in pop‑culture attitude.

Then there were the fish. From the monumental Fish Sculpture in Barcelona’s Olympic Port to undulating lamps and installations, Gehry treated the fish form as a recurring motif—a kind of personal logo that nodded to his childhood memories of his grandmother’s carp and to the idea of movement in water translated into metal and light.

In the 1990s and 2000s, Gehry’s studio became a laboratory for digital design. Their use of advanced 3D modeling software to rationalize free‑form shapes helped pave the way for today’s parametric and algorithmic architecture. Many younger “starchitects” owe their workflows—and occasionally their aesthetic bravado—to Gehry’s technical experiments.

Praise, Criticism, and the Cost of Icon Status

Gehry’s celebrity also attracted sharp criticism. Detractors saw his work as expensive sculpture with limited concern for context, social housing, or day‑to‑day urban issues. Some projects, like the MIT Stata Center, faced legal disputes over leaks and construction problems, feeding narratives that form had outrun function.

There were also broader questions about the “starchitect” era itself—an age of photogenic one‑off landmarks sponsored by corporations and city branding campaigns. In a time of climate crisis and housing shortages, Gehry’s gleaming metal skins could feel like a relic of a more extravagant, less anxious century.

“I don’t make ‘icons’—I try to make places. If people turn them into icons, that’s their business.”

Yet even critics often acknowledged his underlying seriousness about structure and space. Many Gehry buildings, once you get past the photogenic shell, are careful, even traditional, in how they handle circulation, natural light, and the experience of moving through a room.

Gehry in Pop Culture: From “The Simpsons” to Album Covers

Gehry’s influence extended far beyond architecture magazines. He turned up in episodes of The Simpsons, inspired album art and music videos, and became a go‑to visual shorthand whenever film or TV wanted to signal “the future” or “avant‑garde culture.” His buildings became selfie backdrops long before the term existed.

That pop‑culture presence also made Gehry a gateway figure. For many people who never cracked an architecture textbook, his buildings were the first to make design feel like part of mainstream cultural conversation—no different from discussing a new movie, album, or video game release.

Legacy and Looking Ahead: What Gehry Leaves Behind

Gehry’s death at 96 closes a monumental chapter in architecture, but the questions he raised are very much alive: What should buildings do for cities beyond providing shelter? How much should they entertain? Can radical form coexist with social responsibility and environmental urgency?

As younger generations of architects lean into reuse, low‑carbon materials, and community‑driven design, Gehry’s more lavish metal‑clad works may look like artifacts from a different economic and ecological mood. Yet his insistence that buildings can be emotionally charged, culturally central experiences remains deeply relevant.

In that sense, Gehry’s greatest legacy might not be any one museum or concert hall, but the way he expanded the public’s appetite for ambitious design. Whether rendered in timber, brick, or recycled composites rather than titanium, the next generation of “wow” architecture will still be living, in some way, in Gehry’s long, shimmering shadow.

For now, the best way to understand Frank Gehry is still the simplest: stand in front of one of his buildings, walk inside, and let the space argue its case. Love it or not, you will almost certainly remember it—an outcome most architects can only dream of.