Five Years After the First COVID Shot: How a Breakthrough Became a Trust Crisis—and How We Rebuild

Five Years of COVID Vaccines: How a Breakthrough Created a Public-Health Trust Crisis

Over five years, nearly 14 billion COVID-19 vaccine doses have been delivered worldwide—an astonishing scientific achievement that has saved millions of lives. Yet alongside this success, something more fragile has been quietly eroding: public trust in vaccines and public health institutions.

Drawing on insights from physician and science communicator Kristen Panthagani and emerging research, this article unpacks how we arrived at this moment, what the evidence actually says about COVID vaccines, and practical steps you can take—whether you’re a concerned parent, a clinician, or simply vaccine-hesitant—to navigate information, risk, and trust more confidently.

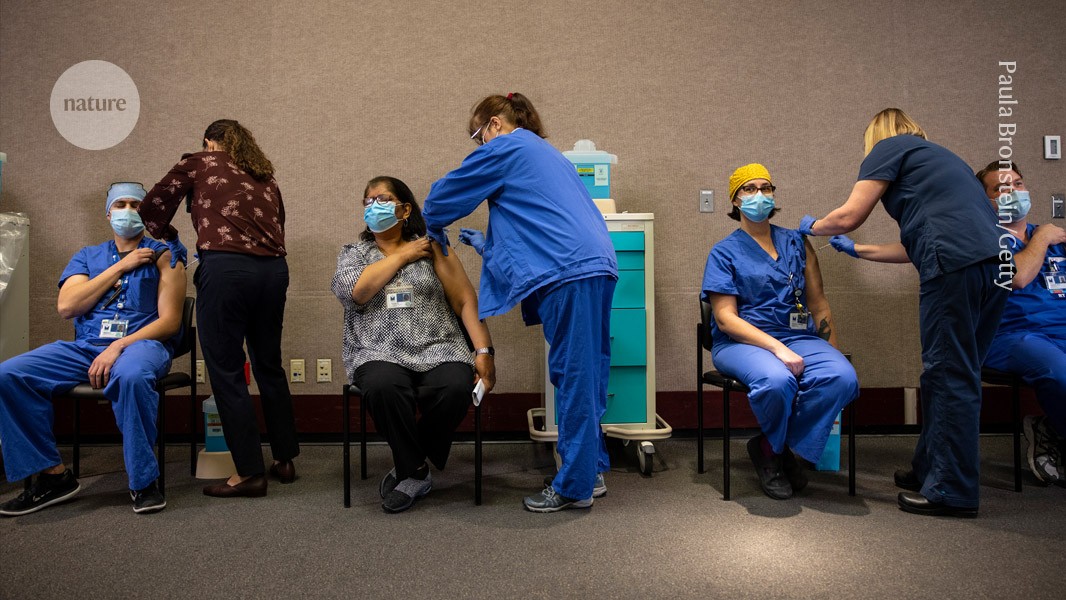

On 8 December 2020, a 90-year-old woman in the United Kingdom rolled up her sleeve and became the first person outside a clinical trial to officially receive a COVID-19 vaccine. In the months that followed, vaccines were developed, tested, authorized, produced, and delivered at record speed.

Five years later, we’re living with two parallel realities: vaccines that dramatically reduced severe illness and death—and a public-health environment in which vaccine skepticism is louder and more politically charged than at any time in recent history.

The New Public-Health Problem: Falling Trust in Vaccines

Surveys across multiple countries now show declining confidence not only in COVID vaccines, but increasingly in routine childhood vaccines as well. This is especially concerning because vaccines against measles, polio, and other infections have decades of safety and effectiveness data behind them.

Kristen Panthagani, a physician and science communicator who has spent years answering vaccine questions online, notes that many people are not “anti-science”—they are overwhelmed, confused, or burned by past experiences:

“Most people I talk to are not hardline anti-vaxxers. They’re trying to make the best decision they can for their family in a firehose of conflicting information.”

When trust falters, two things tend to happen:

- People delay or skip vaccines, leaving more room for outbreaks.

- Public-health messaging becomes politicized and polarizing, making productive conversation harder.

Five Years, 14 Billion Doses: What Did COVID Vaccines Actually Achieve?

Globally, nearly 14 billion COVID vaccine doses have been administered since late 2020. While estimates vary, multiple large analyses published in peer-reviewed journals such as The Lancet Infectious Diseases and Nature Medicine suggest that vaccination prevented millions of deaths worldwide, particularly in the first years before widespread infection-acquired immunity.

Importantly, the goal of COVID vaccination changed over time:

- Early pandemic (2020–2021): Prevent as many infections, hospitalizations, and deaths as possible.

- Later waves (Delta, Omicron and beyond): Focus on preventing severe disease and death, recognizing that stopping every infection was no longer realistic.

As variants evolved, vaccines became less effective at blocking mild infection but continued to offer strong protection against hospitalization and death, especially after booster doses in older or high-risk groups. This nuance—“less protection against infection, strong protection against severe outcomes”—was technically accurate but hard to communicate in simple headlines.

How a Scientific Breakthrough Became a Trust Crisis

The drop in vaccine trust is not just about the vaccines themselves. It’s about how science, politics, and communication collided under pressure. Research and frontline experience point to several overlapping drivers:

- Speed bred suspicion. Many people struggled to believe that a vaccine developed so quickly could be safe, even though the mRNA technology had been under study for years and safety steps were compressed—not skipped.

- Shifting guidance felt like dishonesty. As scientists learned more, recommendations on masks, boosters, and vaccine goals changed. To many, these updates felt like “backtracking” rather than normal scientific refinement.

- Misinformation filled every gap. Social media rapidly amplified claims that were misleading, taken out of context, or outright false, often framed to provoke strong emotion rather than dialogue.

- Real side effects were sometimes minimized. Conditions like vaccine-associated myocarditis in young males and rare blood-clotting events with certain vaccines were real but uncommon. When people felt these were downplayed, it eroded confidence even among those who still chose to vaccinate.

- Politics overshadowed nuance. In some regions, vaccine decisions became tribal identity markers—less about risk–benefit and more about which “side” you were on.

“People don’t lose trust just because bad things happen. They lose trust when they feel those bad things were hidden, spun, or dismissed.”

Panthagani and others argue that acknowledging uncertainties and rare harms openly—while still being clear about the overall benefits—is central to rebuilding credibility.

A Real Conversation: From “No Way” to “Let Me Think About It”

Several clinicians have described a similar pattern in their practice. Here is a composite case based on multiple real-world encounters:

A 42-year-old father comes into clinic with his teenage daughter. He starts the visit with: “We’re not doing the COVID shot. I don’t trust it. It was rushed, and I’ve seen posts about heart issues.” He’s calm but firm.

Instead of launching into a lecture, the clinician asks, “Can you tell me what you’ve seen that worries you most?” Over the next 10 minutes, they talk about:

- His friend’s mild chest pain after a booster.

- His daughter’s anxiety about missing school if she feels unwell afterward.

- His belief that “kids don’t get that sick from COVID anyway.”

The clinician validates the concern about myocarditis, explains how often it’s seen after infection versus vaccination, and reviews the teen’s individual risk factors. They agree to table the decision, share a few accessible resources, and revisit it at the next visit.

At follow-up, the father says, “I’m still not 100% sure, but I feel like I actually understand the risks now.” The daughter chooses to get vaccinated. The father waits, then decides to get a dose before visiting an older family member.

What We Know Now About COVID Vaccine Safety and Risks

After billions of doses and continuous monitoring, the safety picture for COVID vaccines is much clearer than it was in 2020. No medical intervention is risk-free, and COVID vaccines are no exception—but most serious adverse events remain rare compared with the risks of COVID infection itself.

Risks that have been clearly identified

- Myocarditis and pericarditis: Most common in younger males after mRNA vaccines, typically within days of the second dose. Most cases have been mild and resolved with rest and anti-inflammatory treatment, but ongoing follow-up is important.

- Rare clotting events: Certain adenovirus-vector vaccines have been linked to a very rare clotting disorder involving low platelets, leading some countries to adjust which age groups receive these products.

- Allergic reactions: Severe allergic reactions (anaphylaxis) are possible but rare, which is why vaccination sites observe people for 15–30 minutes after injection.

How these compare to COVID infection

Large comparative studies generally find:

- Myocarditis is more common after COVID infection than after vaccination, especially in young males.

- COVID infection carries additional risks—such as blood clots, stroke, and long COVID—that vaccines help reduce by lowering the chance of severe disease.

Beyond the Needle: Deeper Roots of Vaccine Mistrust

For many communities, mistrust did not begin with COVID. Historical abuses, unequal access to care, and everyday experiences of dismissal or discrimination shape how recommendations are received.

Studies in medical sociology and public health highlight several recurring themes:

- Historical injustices: Unethical research practices in the past, such as the Tuskegee syphilis study, continue to influence perceptions in some marginalized communities.

- Unequal burden of disease and access: Communities hit hardest by COVID sometimes felt they were “last in line” for testing and early treatment but “first in line” for vaccination campaigns, fueling suspicion.

- Communication that talks at, not with, people: When messaging ignores people’s lived experiences or questions, it can reinforce a sense of being controlled rather than supported.

“Trust is local. People are far more likely to follow a recommendation from a clinician, faith leader, or neighbor they know than from a distant agency logo.”

If You’re Unsure About Vaccines: A Practical, Step-by-Step Framework

Feeling hesitant or conflicted about COVID vaccines—or any vaccine—doesn’t make you anti-science. It makes you human. Here’s a structured way to approach the decision without getting lost in the noise.

1. Clarify your specific concern

Instead of “I don’t trust it,” try to name what feels most worrying:

- Long-term side effects?

- Fertility or pregnancy?

- A particular condition you or a loved one have?

- Distrust of institutions or pharmaceutical companies?

Being specific makes it easier to find focused, credible answers rather than falling into an endless scroll of generalized fear.

2. Compare risks fairly

Whenever you ask, “What are the risks of this vaccine?” add, “compared with what?”

- What is my risk of severe COVID, given my age and health?

- How common are the side effects I’m worried about, after vaccination versus after infection?

3. Use a “three-source” rule

Before you accept a claim, especially a frightening one:

- Check at least one official public-health source (e.g., WHO, your national health agency).

- Look for coverage in a mainstream science or medical outlet (e.g., major health systems, well-known medical centers).

- Discuss it with a clinician who is willing to engage with you respectfully.

4. Decide your “acceptable uncertainty”

No choice—vaccinating or not vaccinating—offers zero risk. Ask yourself:

- Which risk profile can I live with more comfortably?

- How would I feel if I experienced a rare side effect after vaccination?

- How would I feel if I or a loved one were hospitalized from COVID and I had declined vaccination?

For Clinicians, Educators, and Public-Health Leaders: Rebuilding Trust, One Conversation at a Time

Panthagani’s work, and broader research on risk communication, suggests some practical approaches for professionals trying to engage a skeptical public.

1. Lead with listening, not with charts

- Begin by asking: “What have you heard?” or “What worries you most?”

- Reflect back what you hear before offering corrections or data.

2. Be open about uncertainty and rare harms

- Acknowledge when evidence has changed and explain why (“We have more data now…”).

- Name known rare side effects yourself, instead of waiting for patients to bring them up.

3. Use values-based framing

Connect recommendations to values the person already holds:

- Protecting vulnerable family members.

- Keeping kids in school and activities.

- Maintaining personal and economic stability.

4. Avoid shaming language

Shaming (“people who don’t vaccinate are irresponsible”) may feel cathartic but tends to harden positions. Respectful curiosity keeps doors open.

Before and After: How COVID Changed the Vaccine Conversation

The past five years have redrawn the public-health landscape. Here’s a high-level comparison to clarify what actually changed.

Before COVID

- Routine childhood vaccines widely accepted in many countries.

- Vaccine debates present but more niche and less politicized.

- mRNA vaccines largely confined to research and early trials.

Five Years After

- COVID vaccines normalized mRNA technology and may pave the way for new vaccines against other diseases.

- Vaccine attitudes now strongly linked to political and cultural identity in some regions.

- Increased scrutiny—and sometimes fear—of public-health agencies and pharmaceutical companies.

Finding Reliable Vaccine Information in a Noisy World

Sorting facts from fear is hard when every scroll brings a new claim. A few practical strategies can help you protect your peace of mind while staying informed.

- Favor sources that show their work. Look for articles and explainers that link to original studies or official data rather than simply asserting conclusions.

- Notice emotional manipulation. Posts that rely heavily on outrage, fear, or mockery—on any “side”—are less likely to give a balanced view.

- Be cautious with anecdotes. Personal stories are powerful and important, especially around side effects, but they show what is possible, not how likely something is.

- Ask your clinician where they get their updates. Many use professional societies, continuing education modules, and curated summaries that the general public can sometimes access as well.

Where We Go From Here

Five years after the first COVID vaccination, we are living with a paradox: vaccines that prevented immense suffering, and a level of public skepticism that threatens not only our response to future pandemics but also the foundation of routine immunization.

We cannot undo the confusion, fear, and genuine harms some people experienced. But we can choose how we respond now: with humility, better communication, and a commitment to meeting people where they are rather than where we wish they were.

Whether you are vaccine-hesitant, fully vaccinated, or somewhere in between, you have a role in this next chapter:

- Ask honest questions and seek answers from multiple, credible sources.

- Give others the same listening space you’d want for yourself.

- Support local clinicians and communicators striving to provide clear, balanced information.

Trust will not return overnight. It will be rebuilt slowly, conversation by conversation, dose by dose. Your willingness to stay curious, to update your views as evidence evolves, and to talk with others in good faith is part of that healing.

Next step: Identify one trusted health professional or resource you can turn to with your vaccine questions this month—and bring them your most important concern. That single conversation is a powerful place to start.